“Popular Information”—the title is taken from James Madison—is an important political newsletter written and published by Judd Legum. It leans decidedly left and has done a lot of good work over the years.

Recently Legum turned his attention to what he believes is a Christian Nationalist training program for Florida public school teachers.

“Florida school teachers trained to teach Christian nationalism” claims the headline. The three-day program supposedly equips teachers to “indoctrinate students in the tenets of Christian nationalism, a right-wing effort to merge Christian and American identities.”

What does this right-wing merging of identities effort look like? Legum presents the following:

– teachers were told that “Christianity challenged the notion that religion should be subservient to the goals of the state,” and the same hierarchy is reflected in America’s founding documents

– a slide quotes the Bible to assert that “[c]ivil government must be respected, but the state is not God.” Teachers were told the same principle is embedded in the Declaration of Independence.

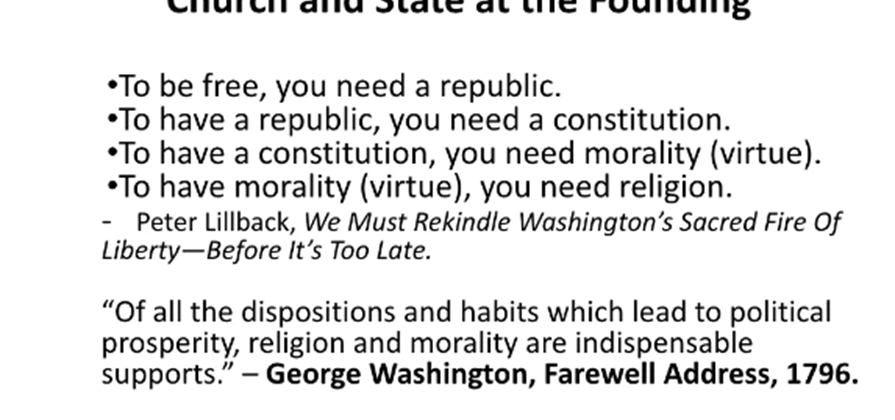

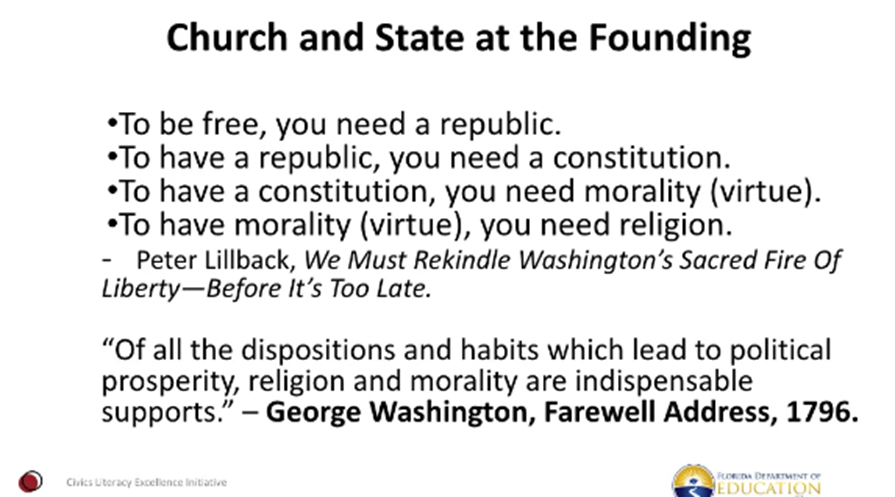

– a slide claims the founding fathers believed religion was an essential support to republican government:

– a Florida middle school teacher reports that in one session “the presenters used the King James Bibles to illustrate their points. ‘I was absolutely gobsmacked,’ she said.”

– a presenter from the conservative Acton Institute claimed that “Judaism and Christianity were more influential on the founders than any Enlightenment philosopher.”

– slides claimed “that the basis of law in the United States is the Ten Commandments (‘Decalogue’) and that the phrase ‘all men are created equal’ is derived from the biblical concept that ‘man is made in the image of God.’”

– sociologist Andrew Whitehead, who has written extensively on the topic, is quoted as saying that the materials are part of “the Christian nationalist project” which is “to fuse ‘a very particular expression of Christianity with American civic life that the government upholds and vigorously defends.’”

As a historian, I can’t say I find anything here very remarkable or controversial, much less sinister. Some of the claims made in the training are more sweeping than an historian would be comfortable with, but that’s true of almost any effort to discuss revolutionary era thought, certainly no more so than the oft-heard “the founding fathers were all deists.” Were there any eighteenth-century political theorists in America or in England who didn’t believe religion played an important role in society? The arguments were typically between the proponents of reasonable and revealed religion.

The idea that the Ten Commandments were “the basis of law” seems overstated, but perhaps not as much as one might think if you were looking at state and local ordinances. Claiming that “Judaism and Christianity were more influential on the founders than any Enlightenment philosopher,” is also a generalization few historians would want to endorse, but it does acknowledge that both religion and philosophy were parts of their worldview, which is true.

In the end, I’m at a loss to see what “very particular expression of Christianity” is being fused into the nation’s politics here. It’s hard to imagine how any of this would have much of an effect on the thinking of the typical middle- or high-school student.

If this is as bad as it gets, even in Florida, it’s going to be a long road to Gilead.