More than just how to shake it off, it turns out

Several years ago my institution’s new provost called my office phone, which hadn’t rung in years. She’d heard a rumor that I was showing child pornography in my journalism classes and needed answers. After a few minutes’ discussion she admitted the provenance of the claim: a social media post, where I’d suggested that too few people know the difference between a film’s critique of predation and its advocacy of the same. A more robust humanities education, I posited on Twitter, might be one antidote.

My Tweet might have lacked intellectual humility, but it was not advocating for child pornography, nor was I teaching pornography at the Christian college where I’d been a professor for twenty-some years. In a too-long conversation my provost finally accepted the absurdity of that claim and, hopefully, revised her policy of believing an anonymous complaint about a faculty member at face value.

I thought back to that earlier exchange following the release of Taylor Swift’s eleventh album, The Tortured Poets Department. Once again discourse about a creative work is unfolding with little understanding of, or reliance on, the critical skills of reading and interpretation that a humanities education accords. Hot takes about Swift call her recent lyrics blasphemous and evil, a mockery of God and Christians especially. Of course folks in my parents’ generation said similar things about the music my peers listened to, symbolized in a thousand record burnings of 80s albums during church youth group meetings. But in some ways objections to Swift feel different, and even less informed. Fundamentally, the misapprehensions about her lyrics reflect the challenges of a post-literate society when so few people are reading, and fewer still are reading critically.

This is something about which most educators agree, including those of us who teach English literature: Our classrooms are no longer filled with voracious readers. Writing for Slate magazine, Adam Kotsco notes that today’s students struggle with even short reading assignments, unable “to do more with written texts than extract decontextualized take-aways.” He blames the distracting and addictive nature of smart phones, as well as the pandemic, which created significant learning losses for many students. But adults fare poorly when it comes to reading as well, with nearly half of all Americans reading zero books last year. According to one study almost half of all Americans read and comprehend below a sixth-grade level. A lack of informed readers might be one more reason for poets to feel tortured.

Some folks have insisted that children shouldn’t listen to Swift’s album. A well-known pundit said supporting this work was indefensible, and another called her music foolish and anti-Christian. But I want to argue that Taylor Swift actually encourages critical understanding, potentially helping her legion of followers to become better thinkers and readers. And The Tortured Poets Department itself is an excellent argument for the humanities, while also providing one potential antidote to our current cultural deficiency to read closely and well.

This needs to be said: I am not a Swiftie. My tastes run more to The Chicks and Beyonce than to Taylor, and I didn’t pay much attention to the singer until late last year when she started dating football star Travis Kelce and some far-right commentators lost their minds, calling her a gold-digger and attention-seeker. This level of hate for a beloved pop star intrigued me, as did the impact she was having on the game, as so many girls were now spending Sundays watching football, hoping to catch sight of their hero. So many, in fact, that a company created a tear-jerking Super Bowl commercial about the phenomena.

Following the release of The Tortured Poets Department, I wondered if Taylor Swift might have the same influence on a generation more inclined to Tik-Tok and Instagram than to explicating poetry. My conclusion? Rather than issuing prohibitions against listening to her music, insisting that Swift is anti-Christian and evil, it might make more sense to celebrate the ways Swift inspires listeners to interpret her lyrics.

Young girls especially have considerable interest in the figurative language Swift is using, and spend significant time trying to decipher the metaphors she sings, as well as her allusions to mythology, the Bible, and literary history. Swift’s music might also encourage young readers to explore the other writers she mentions, while simultaneously arming young people with the tools they need to really decipher the tensions at the heart of all good literature: the difference between good and evil; what it means to be human; how we can find right relationship in a world beset by brokenness.

Such analytical acumen seems missing from many of the criticisms leveled against The Tortured Poets Department. In her most recent album Swift, who has publicly identified as a Christian, uses religious metaphors not to demean Christians, as some commentators have insinuated. Instead, in songs like “But Daddy, I Love Him” Swift alludes to the Bible to call out the hypocrisy of church people whose self-righteousness covers their judgment, the den of vipers “dressed in empath’s clothing” who speak “sanctimonious soliloquies” but possess little in the way of actual Christian love. Rather than mocking God, Swift relies on religious imagery in this and other songs to critique those who pass judgment using God’s name—another occasion when having an understanding of the difference between advocation and critique might be helpful.

This is something my English department students get. They’ve deftly made connections between Swift and the literature they’re reading in class, noting that Swift alludes to Greek mythology, Shakespeare, Emily Dickinson, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and others. Truly comprehending her songs means knowing these allusions well. When I talked with English majors about the hate Swift’s album was receiving, they responded with exasperation. Clearly, they argued, Swift is using figurative language, and listeners would be foolish to assume that the salvific images Swift writes—from “rolling a stone away” to being “crucified”—mean she is mocking Jesus. “It’s clearly a metaphor,” one student told me, with a masterful eyeroll. “Why do people have to be so dense?”

We examined, then, why people do have to be dense: because they are reading less. Because they haven’t been taught to read well. And also because Swift is a convenient target for other people’s ire: It’s easy to disregard a female pop star whose fans are, first and foremost, girls and young women. Surely an artist singing about forlorn love and inspiring her fandom to make friendship bracelets wouldn’t make literary and biblical allusions, nor would her young listeners understand them, right? Fundamentally, the rejection of Swift’s work suggests a certain worldview. After all, Kaitlyn Schiess said in The Holy Post podcast, “I do find it a little grating that people are so upset about use of biblical language when it comes to Taylor Swift, but not when Republican politicians use scripture for their political purposes.”

Some folks might express dismay that an English professor (and a Christian college professor at that!) would support an artist like Swift. But my academic department is committed enough to the value of Swift’s music that we are hosting an academic conference next fall focused on Taylor Swift, her songwriting, her faith, and her fandom. At a time when literacy skills are lacking, the many fans who digest Swift’s work should be celebrated, as should her accomplished songwriting. Swift is offering one way to stoke not only a love for reading but for reading well. Those of us committed to that endeavor should rejoice.

Melanie Springer Mock is Professor of English at George Fox University. Her books include Finding Our Way Forward: When the Children We Love Become Adults (2023), Worthy: Finding Yourself in a World Expecting Someone Else (2018), and If Eve Only Knew: Freeing Yourself from Biblical Womanhood to Become Who God Expected You to Be(2015). Her essays have appeared in Christian Feminism Today, Literary Mama, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Brain, Child, and Runner’s World, among other places. Much of her work focuses on her experiences parenting, feminism within Christian context, and social justice.

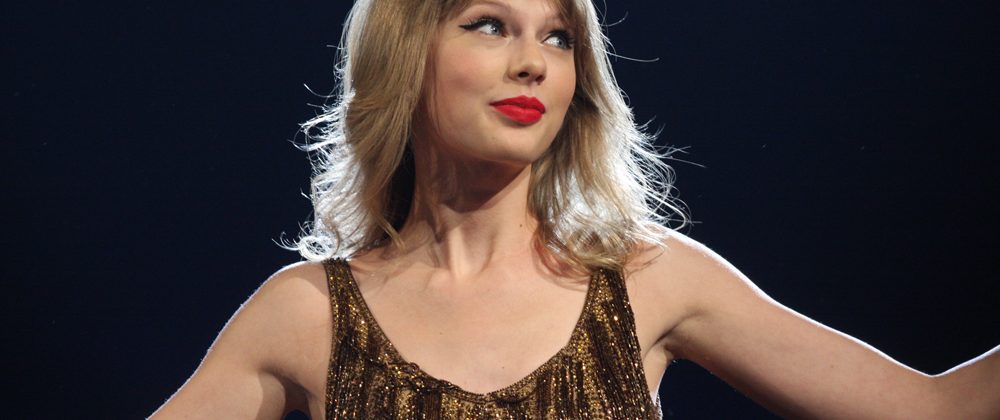

Image: Wikimedia Commons