When the Bard was off his game

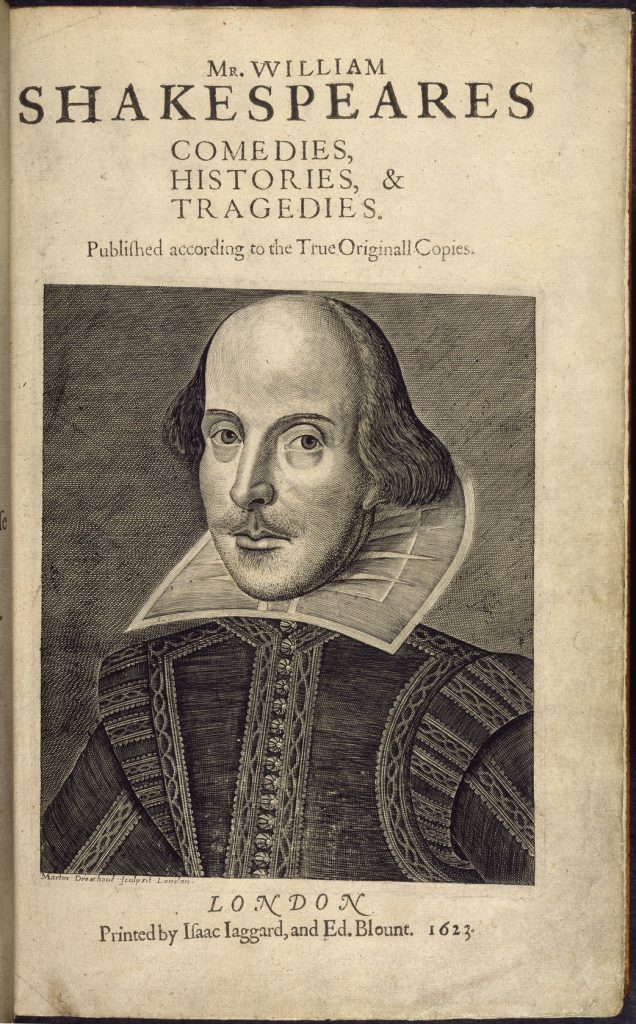

To determine which of Shakespeare’s plays are the worst, one first has to determine which plays are Shakespeare’s. I have always blithely relied upon an introductory volume I happened to purchase in my early twenties, Gareth Lloyd Evans, The Upstart Crow (1982). It lists thirty-seven plays. Not long thereafter I started collecting the Folio Society editions. Fortuitously, that series had the same list. (Thus Pericles and Henry VIII are in, but not The Two Noble Kinsmen or Edward III.)

In my youthful zeal I determined to read them all. Looking back, I can see that this was a byproduct of my spiritual formation. In my childhood, I had been handed a Bible with sixty-six books in it (no need to worry about Judith or Maccabees) and told to read them all. I am not the kind of person who skips the genealogies. I am, however, quite willing to notice that I was not enjoying Ezekiel nearly as much as I did the Psalms.

I was also taught that when I finished, I was to start over. I have belatedly realized that this assumption has also seeped into my approach to the Bard. Every decade or so some internal clock goes off that tells me that it is time to brush up on my Shakespeare.

I have felt another such urge coming on of late, and perhaps I am writing this in an attempt to fend it off. My mind organizes the thirty-seven into three categories: plays I know I like; plays I know I don’t like; and plays I don’t remember.

It is the last category that gnaws at me. If I hear a title such as Cymbeline or Troilus and Cressida and my mind is a complete blank, I feel a secret sense of failure. I am pretty sure I remember a fragment from at least one play in the trilogy Henry VI, Part I, Part II, and Part III. Isn’t there a Welsh castle besieged, and a king or rightful heir who is talked into renouncing his claim to the throne, which later proves to be a bad idea? I think so, but if you told me confidently that it actually happens in King John, I would be inclined to believe you. (And if I am right, that means I remember nothing whatsoever about King John.)

As to my favorites: when it comes to the tragedies, Macbeth. I am always glad when I return to Julius Caesar. And Lear. I seem to appreciate Antony and Cleopatra more than most people. People usually think it’s about adultery. The part that most interests me is when someone who is truly great is past their prime and off their game. How is one to know if they can pull off one more victory or if this really is the end? Both outcomes seem possible. The scene where Antony responds magnanimously to his friend Enobarbus’s desertion gets me every time. I also have a soft spot for Coriolanus. At particularly infuriating faculty meetings I sometimes fantasize about standing up and shouting, “There is a world elsewhere.”

My favorite living playwright is Tom Stoppard. One of my proudest theatrical boasts is that I saw Arcadia (1993) during its original run at the Royal National Theatre, London. Earlier this year I attended a pleasing production of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead at the Court Theater, Chicago. I went around for days fancying myself a wit by pronouncing, “I think it’s better than Hamlet.” That was all good fun until I once again saw Hamlet, and then my conscience wouldn’t let me get away with my little quip anymore. Still, the Prince of Denmark is not on my shortlist of favorites.

But there are, of course, a lot of great scripts elsewhere. I think the film Top Hat (1935) is a perfect romantic comedy, a cornucopia of clever retorts and zany plotting. If forced to choose, I would get rid of an unloved Shakespeare play in order to keep it.

In truth, many of the thirty-seven have receded far from any general awareness in our culture, some not without reason. Wheaton, Illinois, where I live, has been staging “Shakespeare in the Park” every August. There have been ten productions so far. Yet these have already included three repeats. Rather than proceed onwards to The Comedy of Errors or The Merry Wives of Windsor, the park has circled back to Twelfth Night, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and As You Like It.

There are Shakespeare plays I would not be so presumptuous as to call bad, but that I would not mind never seeing again: Othello, for instance, or The Taming of the Shrew. I think Titus Andronicus is just flat-out bad, but I will admit that my naturally squeamish disposition might be affecting my judgment. The play I would probably vote out of the canon first is Timon of Athens. My memory of it is of a boring old man whining at the audience incessantly for hours on end.

Not that Shakespeare needs me to come to his defense, but I will also note that one of the more unfair consequences of extraordinary talent is that people start acting as if you are competing against yourself—which, of course, is a game you are bound to lose. Is this film, play, book, or album as good as his or her greatest previous ones? There are those rare, blessed souls whose work just gets better as they go along, but even most geniuses live out an arc that includes a falling off at the end. Antony is past his prime and off his game.

Late Shakespeare—The Winter’s Tale and The Tempest—is very good indeed. It is not easy for anyone, however, to end before the winter sets too far in, to break their staff and stop. It’s difficult to resist the temptation to go back to the office and start tinkering with Henry VIII or The Two Noble Kinsmen.

Timothy Larsen teaches at Wheaton College and is an Honorary Fellow at Edinburgh University. He is the author of John Stuart Mill: A Secular Life and the editor of The Oxford Handbook of Christmas. He is President Elect of the American Society of Church History.

Image: Wikimedia Commons