Before there was Michael, there was Magic

Magic: The Life of Earvin “Magic” Johnson by Roland Lazenby. Celadon Books, 2023. 832 pp, $22.00 (paperback)

Baseball may be America’s pastime, its cultural significance powered by nostalgia even as the game’s popularity dwindles. And football is undoubtedly our national game, the sporting behemoth that draws the most fans and attracts the most attention.

Still, basketball is where America’s brightest sports stars are made. This is where athletes transcend their sport and become icons of popular culture and merchants of cool—Michael Jordan, Kobe Bryant, Lebron James, Stephen Curry, and other household names.

But before all of them, paving the way, was Magic Johnson.

Veteran sportswriter Roland Lazenby has already written well-received biographies of two other basketball superstars, Michael Jordan and Kobe Bryant. Now, in Magic: The Life of Earvin “Magic” Johnson, he tells the story of the man who “opened up the blue-sky vistas for the future of the sport” with his play on the court, and “presaged the coming age of great player power” with his charm, charisma, and influence off it.

The basic contours of Magic Johnson’s story are well-known to most casual sports fans—or, at least, those old enough to remember the 1980s. He first emerged on the national stage as a six-foot-nine-inch point guard at Michigan State, where a showdown with Indiana State’s star forward Larry Bird in the 1979 national title game drew more television viewers than any college basketball game before or since.

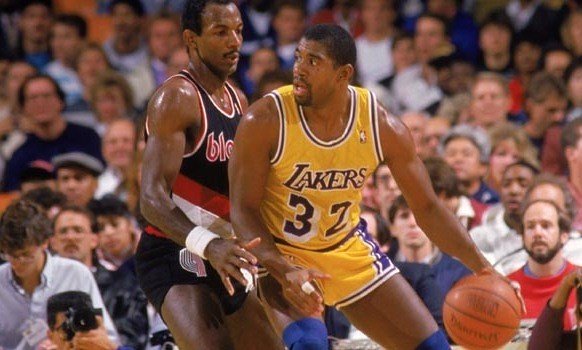

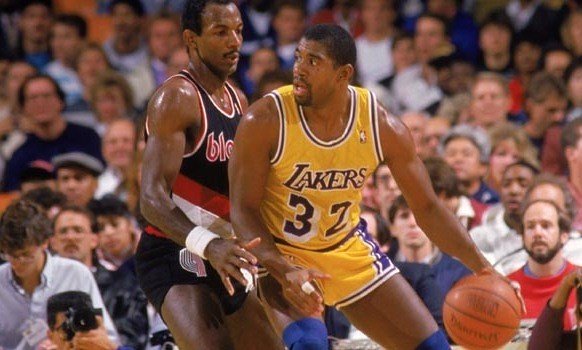

Drafted by the NBA’s Los Angeles Lakers a few months later, Johnson took the reins of a team that already featured a superstar, center Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. With Johnson running the point, by the end of the 1980s the “Showtime” Lakers had won five NBA titles—two more than rival Larry Bird won with the Celtics—helping to usher in a new era of prosperity and popularity for the NBA.

Then, tragedy struck. In 1991, still near the top of his game, Johnson revealed that he had contracted the HIV virus. At the time, HIV/AIDS was highly stigmatized, little understood, and seen as a death sentence. Johnson became an advocate for a better understanding of the disease. By surviving and thriving, he provided hope that a full life might still be possible after AIDS.

After retiring from basketball for good in 1996, Johnson turned his attention to business interests. As an entrepreneur he is still going strong today, with a net worth of more than $1 billion and a minority stake in several pro sports teams, including the Los Angeles Dodgers.

This is the life story that Lazenby traces in 800 pages. Drawing on dozens of interviews, some recent and some collected over the course of four decades in sports journalism, one strength of Lazenby’s book is the sheer number of voices whose memories are included. This is especially true of the first half of the book, where friends, teachers, teammates, and coaches offer insights into Johnson’s upbringing in Lansing, Michigan—including the local sportswriter, Fred Stabley, Jr., who gave Earvin his “Magic” nickname when Johnson was a high school sophomore.

Notably, Lazenby was not able to get Johnson to sit down for an interview. He relies, instead, on those in and around Johnson’s life who were willing to talk. Charles Tucker was one of these people, and he plays an especially large role in the narrative. A school psychologist in Lansing, Tucker had a knack for building trust and cultivating relationships, and he became a mentor and advisor for Johnson, serving as a sports agent of sorts when Johnson first made it to the NBA. Frequent quotes from Tucker line the pages of Lazenby’s book.

Along with interviews, Lazenby has done some historical research. In one early chapter he traces Johnson’s family tree in America, highlighting the resilience of Johnson’s ancestors, people who “fashioned a life in impossible circumstances,” first in slavery and then in a Jim Crow society—his father’s side in Mississippi and his mother’s in North Carolina.

Lazenby maintains an interest in race throughout the book, although he tends to overplay his hand, presenting Johnson in almost mythical hues as a racial peacemaker who “helped to calm white and Black fears about busing and integration” as a high schooler in Lansing, and then as a pro player helped white fans overcome their fear of a predominantly Black league. There is little engagement with the vast literature on sports and race that could provide helpful context to explore the nuances and complexities of Johnson’s place as a cultural symbol of racial harmony.

As he had in his biography of Michael Jordan, Lazenby also attempts to play the role of armchair psychologist, speculating on the inner forces that drove Johnson to greatness. Lazenby cites Johnson’s struggle with dyslexia early in life, which required him to do extra work to develop his reading skills. This, Lazenby says, helped him to cultivate “an exceptional level of both maturity and emotional intelligence”—a unique ability to read a room and to understand how to connect with people.

Johnson also had “natural, loving inclinations” that made him a great leader; he was generous and wanted people around him to feel welcomed and valued. At the same time, he had a firm desire for control. Johnson’s play on the court seemed to reflect this. He preferred to pass more than to shoot, averaging more assists per game than any other player in NBA history. But as teammates and coaches realized—starting with George Fox (high school) and Jud Heathcote (college)—Johnson needed the freedom to do things his way.

Paul Westhead learned this firsthand, too. The Lakers coach won an NBA title in Johnson’s rookie season. But two years later, just eleven games into the season and after a five-game winning streak, tensions between the two came to a head. Johnson wanted to run the fastbreak while Westhead wanted to slow things down and go through Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. Speaking to reporters after a win against the Utah Jazz, Johnson delivered what amounted to an ultimatum to either trade him or fire Westhead. Within a day, Westhead was gone.

Lazenby tries to make sense of Johnson’s unique combination of charm, creativity, and ruthless competitiveness. “There had been other big men before him eager to dribble and pass and display their own genius, but Johnson would prove to be the one, the single figure with the iron will and supreme talent to impose his vision on the game,” he writes. “Make no mistake, it was all carefully disguised in his quick and easy smile . . . but it was there, cold and calculating and undaunted.”

Johnson’s fierce competitiveness came out, too, in his rivalries with friends and foes in the 1980s. Some of the most interesting sections of the book feature Lazenby’s take on well-known stories involving Johnson’s complicated relationships with fellow NBA stars like Larry Bird, Isiah Thomas, and Michael Jordan.

Religion provides a subtle through line in the narrative as well, humming below the surface. Readers learn early on of the importance of faith for Johnson’s parents, Earvin, Sr., and Christine, who faithfully attended a Missionary Baptist church. During Johnson’s childhood, his mother converted to Seventh-day Adventism, which required Saturday Sabbath observance. A compromise within the family was ultimately reached: Earvin, Sr. would attend services on Saturday with his wife, and then on Sunday at the Baptist church, where he was joined by Earvin, Jr.

Although Johnson attended church for most of his childhood, Christian faith did not shape his life in the same way it did his mother’s—not in his public statements nor when it came to his private sexual exploits, which Lazenby covers in several chapters. Lazenby contrasts Johnson with his devout Christian teammate A.C. Green, a virgin who advocated for sexual abstinence and spoke frequently of his faith. “In another world, [Green] was what Christine Johnson might have wished for her son,” Lazenby writes.

Around the time of his HIV diagnosis, Johnson began to emphasize faith more. He married Cookie Kelly, his longtime on-again, off-again girlfriend. The two remain married today, and the couple began attending church services in Los Angeles. But while Lazenby makes note of Johnson’s spiritual influences, he does little to contextualize or explain how they fit within broader trends in American religion.

As Lazenby weaves together details of Johnson’s personal and public life, his subject remains elusive. Lazenby pursues meandering trails and offers layers upon layers of quotations about Johnson, but ultimately his book lacks both the sense of intimacy and the sense of perspective—of the big-picture historical and cultural significance—possessed by the best biographies. Lazenby settles instead for extensive observation and testimony about Johnson through the eyes of others.

In this, there is still much to like. How could there not be, with 800 pages of text and a skilled journalist at the helm? Any fan of basketball will enjoy learning more about an icon of the game, a figure who served as a harbinger of the modern NBA and who transformed the sport with his creativity and charisma.

For those who don’t already have an interest in Johnson, however, it seems unlikely that Lazenby’s biography will break through. It works well as a basketball book; not so well as a book about American culture and society told through the lens of sports. While Magic Johnson helped to pave the way for basketball players to become larger than life figures transcending their sport, this biography is at its best when it remains bound to the court.

Paul Emory Putz is the Director of the Faith & Sports Institute at Baylor’s Truett Theological Seminary. He is the author of The Spirit of the Game: American Christianity and Big-Time Sports, forthcoming with Oxford University Press.

Image: Kip-koech, “Magic Johnson,” Flickr 2013