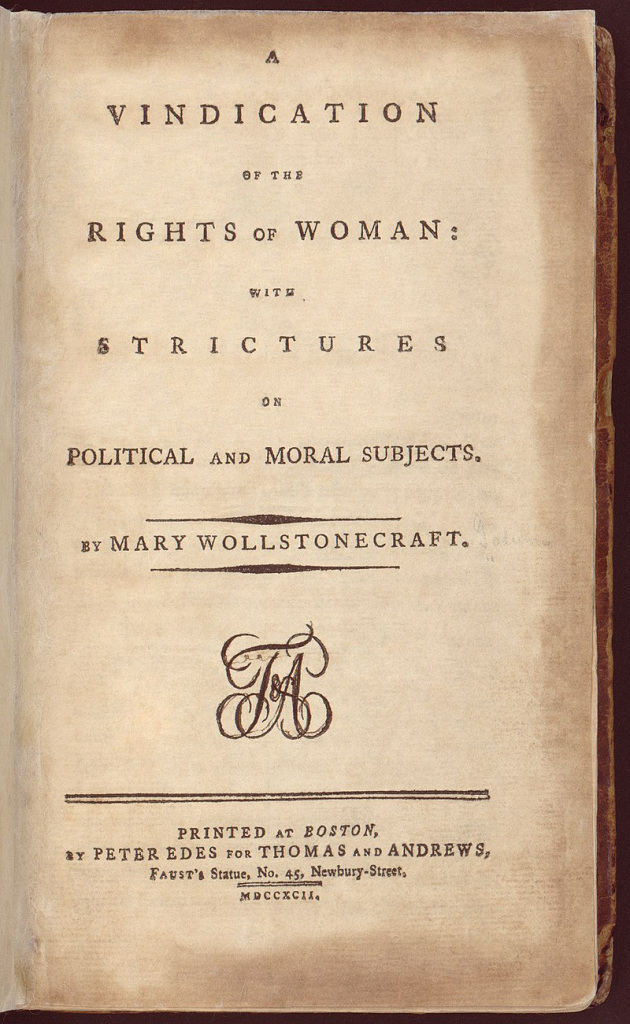

I recently penned a piece here regarding my fondness Jane Austen’s novels. Many scholars have detected an influence on Jane Austen of Mary Wollstonecraft, who wrote roughly one generation ahead of Austen. While there is no direct evidence that Austen read Wollstonecraft, we do know that Austen read the kinds of journals for which Wollstonecraft often wrote. There are certain themes in Austen’s work that suggest a Wollstonecraftian touch. Primary among those themes is women’s education. This subject is at the center of Wollstonecraft’s major work, A Vindication of the Rights of Women. Pride and Prejudice is the Austen novel where the subject is most directly addressed, although one could argue that all her novels touch on education in some manner or another.

There seems to be a resurgence of interest in Wollstonecraft, interestingly among more conservative women intellectuals. Beatrice Scudeler has written about this phenomenon here at Current and has also expertly written on the connections between Austen and Wollstonecraft. Some of these thinkers, most notably Erika Bachiochi, call themselves “sex-realist feminists.” I take this appellation to mean that we should treat the differences between men and women as real, not merely social constructs. Those differences should help form some of our policy, for example maintaining strict distinctions between male and female intimate spaces such as locker rooms and bathrooms, while demanding female inclusion in public spaces (work, politics, etc.).

It was reading Bachiochi’s book The Rights of Women that first piqued my curiosity concerning the relationship between Wollstonecraft and Austen. Bachiochi gives an interpretation of Wollstonecraft that diverges from the typical feminist take. Bachiochi’s Wollstonecraft takes male/female differences seriously, expects high levels of virtue from both men and women (including the virtue of chastity), and believes that one purpose of education is to cultivate virtue. It is Wollstonecraft’s central contention that the “feminine” education given to women of her day ill-served them. Assuming women were inherently less rational than men (or just plain old irrational), women’s education did not develop that faculty, instead focusing on skills such as music or languages that might enhance one’s sociability. The perceived inferiority of women, then, was actually a deficiency in education.

When reading Bachiochi’s characterization of Wollstonecraft’s thought, I found myself regularly jotting in the margins, “Austen.” I was reminded over and over of similar thoughts and themes in Austen’s work. Both Austen and Wollstonecraft concern themselves with education, the balance of reason versus emotion, the relations between men and women, and how all of these intertwine with virtue.

While I could point to many areas of similarity in thought between the two authors, I wish to point to a few differences. First, it should be said that Austen is simply a better writer than Wollstonecraft. Austen is one of the finest prose writers the English language has ever produced, so perhaps that is unfair, but Wollstonecraft, both in fiction and non-fiction, tends to overwrite. Her work is both verbose and didactic. For example, A Vindication of the Rights of Women contains a chapter entitled “Morality Undermined by Sexual Notions of the Importance of a Good Reputation.” Wollstonecraft takes ten pages to say that actual morality is more important than the reputation for morality. A whole chapter is spent on what could be said in one sentence.

Also, and theoretically more importantly, Austen has a sense of humor. Wollstonecraft often attacks injustices with vehemence. Austen does so with humor. This is tied to what I think is Wollstonecraft’s overreliance on reason. Wollstonecraft’s emphasis on reason is problematic in that there is a tendency to think that society’s conventions, often the result of practice and habit rather than reason, defy a rational defense. But Austen seems to be saying that although we may chafe at certain social conventions, and sometimes we might even violate them, on the whole the attitude toward injustices of these conventions is laughter rather than remaking them based on abstract reason.

You might say that Wollstonecraft is all logos no thymos, all reason no spiritedness. She demonstrates this most vividly in A Vindication of the Rights of Man, her pointed attack on Edmund Burke and his criticisms of the French Revolution. Austen, like C.S. Lewis, understands that the head rules the stomach through the heart. One must have a passionate commitment to liberality, for example, as well as an intellectual understanding of it. Logos and thymos are partners. Austen recognizes the potential injustice of authority, custom, and tradition. But she also recognizes their purpose in shaping a functioning society. Thus, the ironic take on traditional authority rather than the radical take. The purpose of laws and customs is to make up for the deficiency in reason that is natural to humanity.

It is notable that Bachiochi, drawing from Wollstonecraft, believes “justice is the primary virtue that governs relationships between parents and children.” That justice, not love, is the “primary virtue” governing the family is a conclusion that one comes to if one is constructing a family based on pure reason, rather than other variables such as love and affection. This is why I believe those who wish to defend a kind of sexual realism against radical gender theory should eschew the term feminism.

Allan Bloom, in his incisive critique of feminism, gets to the heart of the problem when he writes, “The worst distortion of all is to turn love, a relation that is founded in natural sweetness, mutual caring, and the contemplation of eternity in shared children, into a power struggle.” That, it seems, is the fundamental feminist error. In combatting feminism’s excesses we should not repeat that error. We make a mistake by slapping the name “feminist” on any branch of thought that is particularly concerned with the good of women and defending legitimate female claims. We should be able to defend the feminine without buying into the central fallacy of feminism.

I think it would do a disservice to Austen’s literature to call it “feminist” simply because it is deeply interested in the feminine. Austen’s novels are not concerned with power struggles between men and women. They are concerned with how hearts come together in such a way that is both consistent with and promotes the characters’ virtues, i.e., their quest for moral excellence. Wollstonecraft concerns herself with this quest as well, but perhaps is too wedded to pure reason to see that task to successful fulfilment. As usual, Austen shows us the way.