Almost every day we are told that these are dark times. We can talk about almost nothing without also talking about polarization. So many people seem to feel that things are not good and that they are not doing well enough. We see that reflected in the responses people have to the successes and struggles of athletes and celebrities and businesspeople, who are almost the only kinds of people we ever hear about. It may be that rather than finding a better way to have some of these conversations about polarization and resentment, we should just have a different, better conversation.

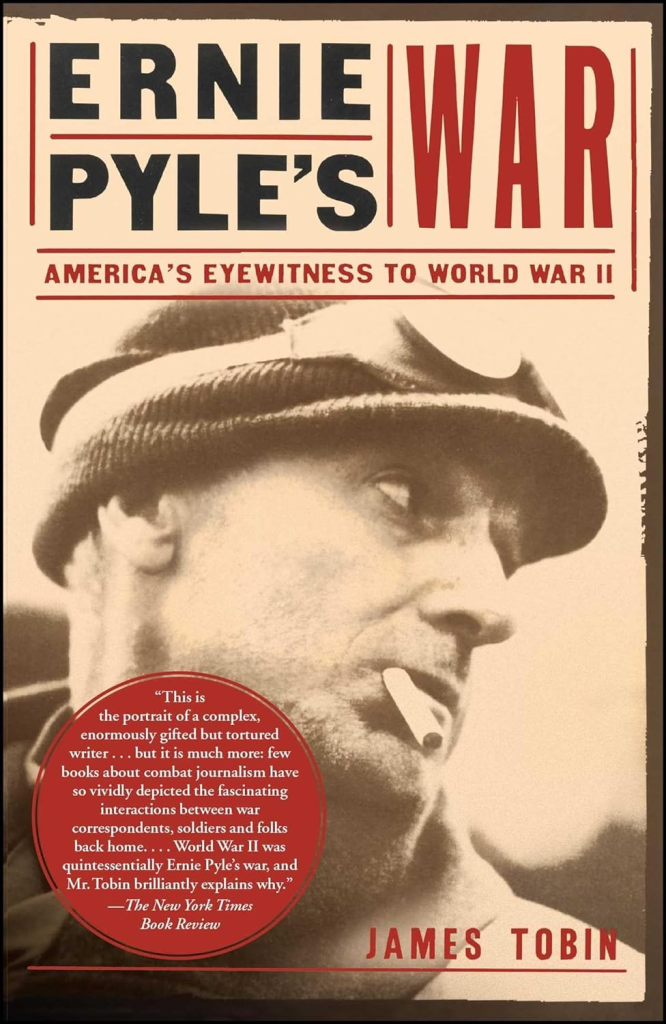

In Ernie Pyle’s War: America’s Eyewitness to World War II, James Tobin explains what made Ernie Pyle perhaps the most beloved wartime correspondent of all time. Pyle had a special ability to represent the common man. His articles highlighted the role of the average soldier and referenced the real lives and experiences and names of normal, everyday Americans being called on to do extraordinary things. Pyle was among the infantry for much of World War II, writing up scenes and relating to people back home what their boys were doing. Pyle himself was the archetypal “little man”—not very big, not especially handsome, a farm boy from rural Indiana, someone who worked for a living and for whom life was not always easy. Yet he soldiered on, worked hard, was good to people around him, and dealt with his difficulties without overburdening others.

Ernie Pyle did a great service to his reading public and he was remarkable among his peers, but he was also part of a wider context. As James Tobin explains in Ernie Pyle’s War, Pyle and the admiration of him were part of an era in which the world was being overrun by fascism, economic troubles were very severe, and people were afraid that democracy might be doomed. In that moment, artists and writers wanted to emphasize the American experience and to save America by loving her.

“And what was constant and valid? By 1940, the answer was being trumpeted from movie screens, Post Office walls, and the essays of the literary elite: the People, the ordinary American of factory and farm, the Common Man. In great public murals, WPA artists enshrined the Common Man and Woman as custodians of folk wisdom, symbols of frontier strength and industry, sources of the nation’s salvation. In Our Town, Thornton Wilder discovered deep wells of quiet resilience. The plain man of Main Street rose up as Frank Capra’s Jefferson Smith in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, a fiery preacher of American integrity. Henry Fonda became not only the downtrodden Tom Joad of The Grapes of Wrath, but also Abe Lincoln of Illinois, the archetypal common man.”

We might do well to consider a similar attempt. We worry about the Common Man—how will he vote? Will he be able to pay off his mortgage? His school loans? Will he go to university? Will his obesity slow down? We treat him like a liability, a cause for concern. Surely there are causes for concern, but a little more celebration might go a long way.

Riddle me this: what are some of the best recent books and movies that celebrate the everyday person? Because there is a certain heroism in a long, daily commute to pay for braces and insurance for 2.5 kids who play soccer very averagely. There is courage in the person who is a first-generation college student, whether or not they become a CEO or an astronaut. There is noteworthy dedication and resolve in the long marriage, even when it does not produce “generational wealth.” There is an admirable creativity and appreciation of the arts in the person who plays guitar every evening and whose friends appreciate their gifts, even if their YouTube never accrues more than 200 followers.

We have a real hunger for such acknowledgement and appreciation, even if we do not immediately recognize it. Consider all the venom directed at “elites,” especially “coastal elites.” Almost no one serious identifies as one, but so many people are mad at them. “Elites” have an agenda—all the time, about everything. Elites tell you that marriage doesn’t matter, but they actually all go ahead and get married. Elites don’t respect or understand tradition or religion or skepticism toward science. They are hypocritical and judgy about everything. They do not understand your budgeting problems. They are not troubled by gas or grocery prices. It does not really matter that there is not some organized elite group, that they have no actual agenda, that no one seems to know who “they” are—we’re mad at “them.” Why? A lot has to do with people not feeling represented in what they see on tv or in shows or in movies.

America excels at celebrating those who rise above others, but we need improvement in celebrating everyday Americans. You can have a very good life without becoming rich or visiting over thirty countries or retiring at forty. And we can all acknowledge the very good lives around us that never get televised. Much of the conversation about “resentment” in our society has centered on politics. Politicians need to take seriously the frustrations of people who are losing status, who feel disenfranchised, etc. But politics is only ever part of a more holistic solution. The everyday person could use more acknowledgement in other arenas, as well. It has been a while since Aaron Copland wrote “Fanfare for the Common Man” in 1942. We’re overdue.

As a little closing inspiration, enjoy the opening lines of Walt Whitman’s “I hear America Singing,” with appreciative and valorizing lines for many of nineteenth-century America’s occupations:

I hear America singing, the varied carols I hear

Those of mechanics, each one singing his as it should be blithe and strong,

The carpenter singing as he measures his plank or beam,

The mason singing his as he makes ready for work, or leaves off work,

The boatman singing what belongs to him in his boat, the deckhand singing on the steamboat deck,

The shoemaker singing as he sits on his bench, the hatter singing as he stands,

The wood-cutter’s song, the ploughboy’s on his way in the morning, or at noon intermission or at sundown,

The delicious singing of the mother, or of the young wife at work, or of the girl sewing or washing,

Each singing what belongs to him or her and to none else,

The day what belongs to the day—at night the party of young fellows, robust, friendly,

Singing with open mouths their strong melodious songs.