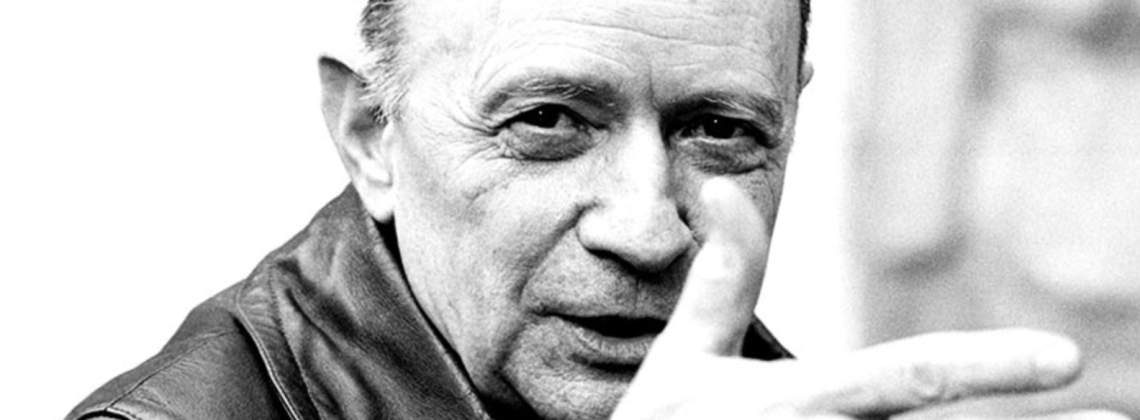

Ellul’s death thirty years ago offers a moment to recall his message

Public familiarity with the internet was still in its infancy when French thinker Jacques Ellul passed away at the age of eighty-two on May 19, 1994. At the time of his death, Ellul was primarily known as a critic of technology whose ideas had influenced an eclectic group of people, including French environmentalists, American evangelicals, Aldous Huxley, and the Unabomber. The main concern of his fifty-some books and one thousand articles, however, was a broader concept that he called la technique. In his most well-known book, The Technological Society, Ellul defined technique as “the totality of methods rationally arrived at having absolute efficiency (for a given stage of development) in every field of human activity.” Ellul contended that technique’s monomania for efficiency, and ultimately for power and financial profit, frequently came at the expense of human flourishing.

The most obvious manifestation of technique was the dependence on machines and the rapid pace of technological change that have come to characterize the modern world. Yet Ellul also insisted that human technique—the organized psychological and sociological manipulation of humans—was likewise important. In the postwar era the medium of television, he noted, consisted of little more than propaganda dressed up as information and entertainment. In many ways, the technological and mass media changes of the postwar period that Ellul wrote about set the stage for the Information Age that began with the advent of the microchip and personal computer in the 1970s. The central role the internet has played since the 1990s in accelerating the changes of Information Age has brought us to a place in which technology and propaganda have converged as never before. This makes Ellul’s ideas more relevant than ever.

It is certainly true that many of the changes in information technology over the past fifty years have improved people’s lives. But while the Information Age has many benefits, in recent years we have become more and more aware of its downsides. To call to mind a few familiar examples: In the 2010s, terrorist groups such as ISIS became skilled at using internet propaganda to recruit new members and instigate violence across the world. During the COVID-19 pandemic, disinformation led to the rise of beliefs that endangered public health. Extremists such as Antifa who participated in destructive riots that rocked many American cities during the summer of 2020 following the tragic death of George Floyd used the internet to organize their activities. Political conspiracies about QAnon and the “rigging” of the 2020 election grew and spread rapidly online before culminating in the attack on the United States Capitol building on January 6, 2021.

Overall, social media has contributed to upticks in loneliness, envy, anxiety, and anger. Jonathan Haidt’s new book The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness makes the case that the advent of the smartphone coupled with greater social media use in the early 2010s were very detrimental to adolescents. Big tech companies have gained the capacities to mine the online data of individuals and monitor their private behavior in ways that Cold War secret police organizations such as the East German Stasi could have only dreamed of doing. We now teeter on the verge of an AI revolution that could exacerbate these trends that have isolated and alienated people, made the truth more difficult to find, and threatened democracy.

Jacques Ellul was not opposed to everything that falls under the category of technique in general and technology specifically. Rather, he argued that these things always come with costs and trade-offs. And it is naïve to assume that new technologies and the proliferation of information are always improvements. Further, for Ellul, like McLuhan, the medium is the message. Ellul was especially concerned that the truncated images people see on television, in magazines, and in billboard advertisements present a distorted version of reality that serves the interests of corporations and politicians, rather than human wellbeing itself.

One of Ellul’s most salient observations was that propaganda is not solely the tool of totalitarian regimes such as the Nazis or the Soviets. In fact, the cleverest propaganda subtlety mixes truth with emotive lies designed to stir people to action. This kind of propaganda can and does thrive in democratic countries with a free press, not to mention widespread internet access. On a deeper level, as a theologian, Ellul associated the plethora of images that accompany mass media with idolatry. As the Information Age has saturated us with quick moving, highly selective visuals to stimulate our desires, and as those AI creates are completely artificial ones to boot, surely Ellul’s warnings are still worth considering, even if modern images are digital instead of graven.

When Ellul was told that the new high-speed TGV train route between Paris and Lyon would save travelers one hour per trip, he did not automatically praise this news. His response was to ask what they would do with this hour. This is the sort of question we should ask today as the Information Age has harnessed new technologies to serve the ends of propaganda at a level far above what was possible during the Cold War. If shopping and working from home will save us an hour each day, what will we do with this time? Will we use it to unplug and pursue healthy activities such as quality time with family and friends, physical exercise, intellectual and spiritual activities, or even to get more sleep? Or instead, will we spend this time in front of a screen mindlessly scrolling through social media, binge-watching shows on Netflix, or, worse yet, videos on Tik-Tok? Do not these latter activities leave us more prone to manipulation, more isolated and anxious? In a contentious election year, will we allow the algorithms of internet search engines and social media to guide us to the “news” that we want to see? Or will we intentionally avoid propaganda and seek out the truth that we actually need to see?

It is not necessary to become a neo-Luddite to take the ideas of Jacques Ellul to heart. But we do need to exercise critical thinking when dealing with technology. And above all, we need to have the awareness to put humanity over efficiency.

Bronson Long is a Professor of History at Georgia Highlands College in Rome, Georgia. He is the author of No Easy Occupation: French Control of the German Saar, 1944-1957.