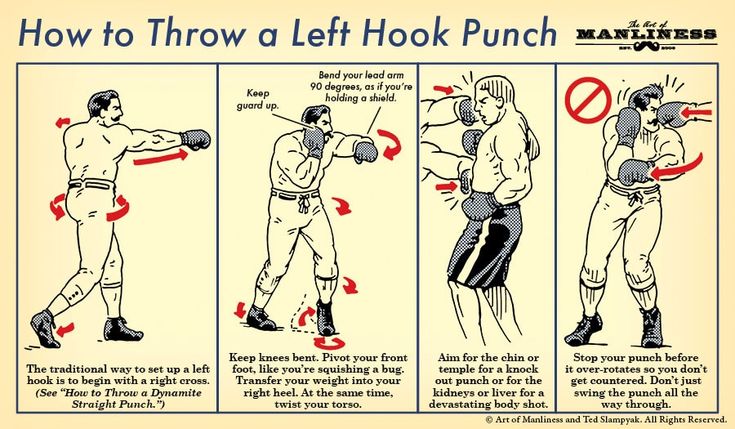

Here is a taste of Jonathan Chait’s review of Astra Taylor and Leah Hunt-Hendrix’s Solidarity. The review is titled, “In Defense of Punching Left.”

“The role of protest is another division between liberals and leftists. While both see protest as legitimate, liberals tend to think of protest as a tool for use on extraordinary occasions. For leftists, it is the primary form of political activity. “History has shown time and again that even a proportionally small number of people, if they are well organized, can have an outsized effect,” they write. Their liberal counterparts naïvely cling to the belief that they can enact policy change merely by winning elections and passing laws: “Despite all that is at stake, too many liberals hold on to the false hope that we can fact-check or vote our way out of these problems.”

One problem created by this reliance on protest is democratic legitimacy. What happens if the demands of the well-organized minority conflict with the beliefs of the disorganized majority? Taylor and Hunt-Hendrix imply that the organized minority is entitled to prevail. They lavish praise on movements calling for police defunding and complain that, “despite the largest protests in U.S. history, many police departments grew” after 2020. But polls showed overwhelming opposition to defunding the police, including among Black Americans, and Joe Biden specifically opposed this policy in 2020.

When conservatives use well-organized factions to steamroll over the preferences of a majority, we call that “minority rule.” Electoral politics, for all its shortcomings, is a more democratic method for resolving differences than bringing bodies into the streets. But this is easy to ignore if you’ve convinced yourself that protest movements represent a more authentic expression of true political justice than the verdict at the ballot box. (It’s all the easier if you’re personally funding the protesters in question.)

The reliance on protest can create legitimacy problems even within the progressive movement itself. When every cause is framed as a matter of absolute moral urgency, which is the lingua franca of protest politics, then no compromise can be brooked. Anti-Zionism is the left-wing cause du jour, but since Solidarity was written before October, the movements whose moral urgency it elevates are those focused on racial justice, climate, and student-debt relief.

The insistence on advancing as fast as possible on all fronts is useful in fostering solidarity among the groups, none of which is ever happy to accept back-burner status. But it immensely complicates the task of creating a governing agenda. The Biden administration nearly abandoned its domestic reform agenda because it couldn’t decide which programs to put aside (and hence which groups to alienate) and appeared to prefer doing nothing until Joe Manchin decided for it at the end of the process.

An additional problem is that each activist issue-group can itself be pulled left quickly by its most committed members. (The stakes for staying on good terms with the left on Israel have quickly escalated from opposing the occupation to opposing Israel’s existence in any form to, increasingly, refusing to condemn the murder of Israeli civilians). The dynamic is magnified when every component of the left is expected to endorse the demands of every other.

Moral clarity and fervor can be useful at times. But they invoke fundamentally unrealistic ideas of how politics and governing can be conducted, and they make it difficult to identify and correct errors on one’s own side. To ask a liberal to join a movement without critiquing its errors and excesses is to ask them to jump aboard a car with no brakes.

Liberals don’t have to endorse every left-wing premise to be a good coalition member. We are welcome to focus on attacking the right while politely ignoring aspects of left-wing thought we find excessive. But when disagreement arises within the progressive family, the liberal’s role is to accept critique from the left without returning it.

When Taylor and Hunt-Hendrix chide liberals for criticizing the left in order to “appear reasonable,” they seem unable to imagine any of these liberals is actually attempting to be reasonable. Who needs reason when the solutions are all so clear?

Read the entire piece at New York Magazine.

Should liberals punch left? Of course they should. Unless, of course, they want to maintain large social media followings and big platforms by creating echo chambers. Check out your favorite author or social media influencer. Does this person EVER punch the other way in their posts?

One of the reasons we founded Current was to provide a place where authors and bloggers could punch both ways. Join us!