Yesterday’s awarding of Pulitzer Prizes reminded me of an award the Pulitzer powers gave in 1991 to a courageous reporter who was anathema in his own newsroom.

That story began exactly 50 years ago when Los Angeles Times editor William Thomas created in 1974 a new beat: media critic. The goal was to do tough reporting on news media, including the Times itself. Thomas gave 31-year-old David Shaw the job and said if he did it well he would probably alienate every reporter in the newsroom.

Shaw did it well. In 1990 he wrote a series of articles showing how major news media, including the Times, displayed pro-abortion bias via words and images. He didn’t make just the obvious comparisons, such as calling abortion advocates “pro-choice” but refusing to call abortion opponents “pro-life.” Shaw complained that his own newspaper referred to a new Louisiana law as “the nation’s harshest.” He noted, “that’s the view of abortion-rights advocates… but abortion opponents regard the legislation as benevolent.”

Shaw also wrote about other word choices: calling a law that kept alive some unborn children “restrictive” rather than protective. He showed how marches for abortion received substantial coverage and marches against it often went unreported. Shaw looked at pictures, or rather the absence of pictures showing unborn children.

Shaw and I communicated because he even recommended a book I had written two years before, The Press and Abortion, 1838-1988, which showed how most major newspapers, after opposing abortion from 1871 to 1962, swung around to a pro-choice or pro-abortion position in the late 1960s and didn’t budge from it.

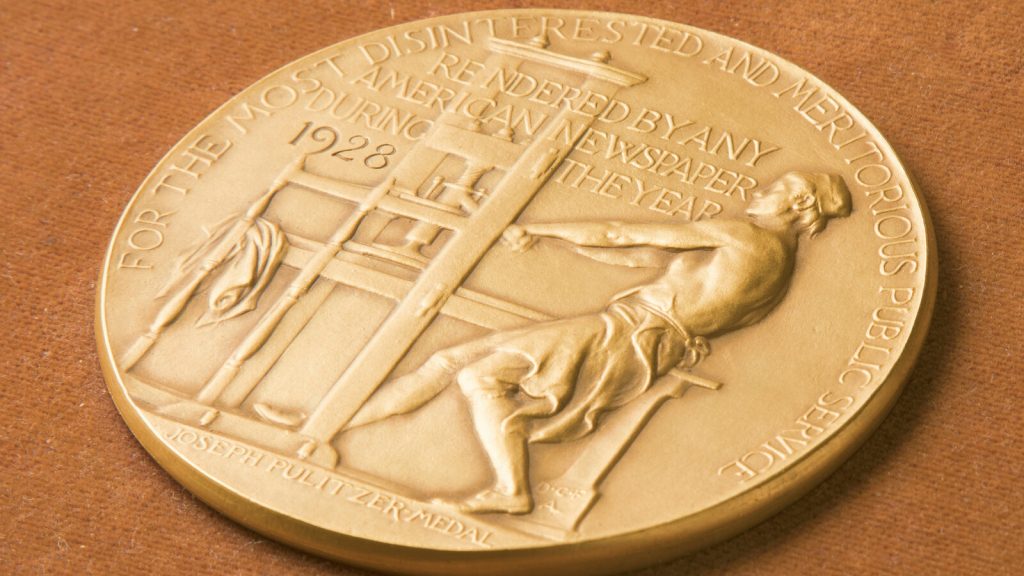

Happily, Pulitzer judges played it straight in 1991 when they gave Shaw a prize for examining how the press covered alleged sexual molestation cases. But when the Times management delivered lots of champagne bottles to the newsroom for a big celebration, the Washington Post reported that “many of the bottles were returned unopened.”

Many of Shaw’s colleagues would not speak to him. But Shaw continued to do honest reporting until he died in 2005, at age 62, from a brain tumor. In 2024, some fine reporters still do good work, but others succumb to ideological pressures or become true believers in Rousseau or Nietzsche.