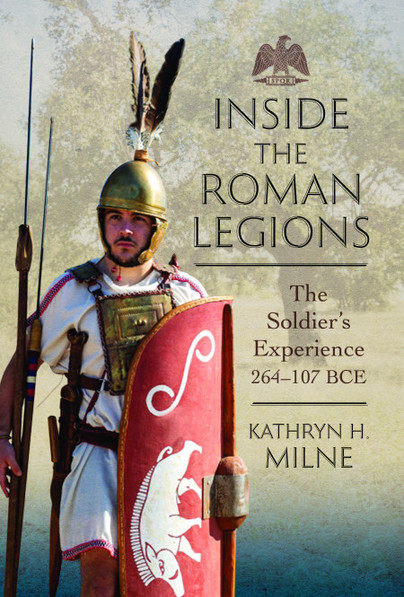

Congratulations to Roman military historian Kathryn Milne on the recent publication of her book Inside the Roman Legions: 264-107 BCE! We celebrate with (what else?) an interview with the author! If you are in the UK, you can get a copy directly from Pen and Sword Books. US release date is in June, and you can get your copy from the place named after ancient horseback archery warrior ladies. Seems appropriate.

Nadya Williams: Congratulations on your book! You’ve spent a long time researching the life of Roman legionaries—I won’t betray your age or mine by trying to estimate just how many years. The most important is, you bring a lot of research and expertise to this book. Who is your audience here?

Kathryn Milne: Thank you! The core audience I have in mind when I write is always going to be people who love the Romans, or in other words, history nerds of all stripes: professional historians, students, and enthusiasts of history who consider it a hobby and learn about it just because they find it enjoyable.

I hope that I have managed to fill in some gaps for professional historians, because I have looked at an often-overlooked section of the population, which is ordinary, everyday people living the life that their time and circumstances demanded of them. For students, I have written about the experiences of being in the Roman military, which is always a popular topic that students like to spend time writing and thinking about, and so I hope I can provide some more material for undergraduates and graduates alike to dwell on what is, honestly, a huge aspect of the lives of male Romans. And for the enthusiasts, I hope they will enjoy as much as I did following along with the complete story of how one goes from A to B in Roman military life, from Roman boy to recruit to trainee to fighter to (hopefully!) retiring out and finding something else, if indeed that’s what you decide to do.

Another audience I always have in mind is current and previous military personnel, and I get a special kick from including age-old aspects of military experience that I know they will recognize. I thought of them particularly when I wrote about moving Roman soldiers to the starting point of their campaign, which in this era is frequently overseas and handled by the navy. The process of boarding must have been really slow, keeping everyone ready for hours and then having them board in a matter of minutes. “Hurry up and wait” is a common saying in many different militaries.

And then there are little details sometimes that seem very real and human, like Scipio Africanus issuing an order to his soldiers as they were embarked on the naval transports, to be quiet and not interfere with the work of the sailors. It’s so obvious that the gist of his order was “sit down and shut up.”

NW: What are some key takeaways you hope readers will gain from reading your book?

KM: In terms of what I want readers to gain, well, it’s primarily the sense of having followed a real and common historical experience through a long period of time. Some important things I wanted to convey were that there were many different paths to take through the military of this time, depending on your temperament. I highlighted opportunities for violent men to put themselves forward and for more reticent or sedate men to take up guard duty, garrison duty or some other necessary task that wasn’t violent and bloody.

Some of these—like being assigned to the garrison of a town and serving out your year or even multiple years like that—I’ve never even seen mentioned in a historical account. I really wanted to voice these experiences and put them back into the historical record, partially, I think, because it’s important to recognize that any military enterprise has all sorts of support personnel made up of people who are absolutely vital but completely invisible.

Another thing I wanted to do was to follow the soldier’s experience for long enough to be able to connect aspects that we usually speak about in isolation. So, sometimes we talk about the influences on the population of, say, certain well-known stories about Roman heroes, where these stories come from, how they are constructed, and what they mean.

I wanted to take the reader through those experiences of growing up with these military stories so that I could prompt them to think about them again, when the situations the young soldiers had only heard about suddenly became pertinent and real. With those two things put together—what they know they are supposed to do, ideally, compared to the description of the situation they are in—you realize exactly what the weight of expectations looks like on these men’s shoulders, whether that is in a battleline preparing to fight hand to hand or in some kind of draconian disciplinary situation.

It wouldn’t have seemed as easy, or the choice as obvious, as in the tales Romans told one another, but that extra dimension of knowing the exact expectations certainly colours how you think about the experience on the spot. So that is what I aimed to do in the book, to illustrate that everything is connected, that experiences and knowledge continually build and interconnect in someone’s life, and that to try to get a good approximation of what it was like to be someone living thousands of years ago, it’s really rewarding to start at the beginning and walk with the person in as linear a fashion as you can.

NW: What were some surprises for you in telling the story in this book? (Because, yes, even after lifelong research, there are still always surprises!)

KM: I learned as much about historians, ancient and modern, as I learned about historical people. Because I was looking to tell a story from start to finish, a lot of the time I was looking into information gaps. A good number of times no-one had addressed the missing issue at all. Sometimes this was because there was no evidence, and while in an earlier era of scholarship it was common to speculate a bit or write chattily that you thought about it but there was no evidence, today usually historians just omit these mystery subjects completely.

Sometimes I discovered that the evidence was actually there, but simply no-one before me had cared to ask the question that I was asking, I suspect because it involved low level, common soldiers whose fates were not of any interest to the elites of society who wrote history in ancient times and have not risen to the interest of the professional historians living in modern times, either.

And then further into the writing of the book I realized that just not bothering to look at information about common people was actually the least upsetting thing about accounts that viewed society from the perspective of elites!

I found myself really annoyed by some posited solutions to missing information that just struck me as absurdly elitist. For example, we don’t really know how casualty numbers were collected in this era. When I looked up the current discussion on the question, I found a very awkward narrative of how there might be rolls recording personnel and then how the amount of men would need to be counted by an officer on the ground, or rough estimates made by eyeballing the camp.

I come from a pretty blue-collar background and it seemed very obvious to me that you could just… ask them? Every unit knows who came back from the battle and who didn’t, just go round and ask each tent or each century or each maniple who is missing. So, I wrote that.

And I think this kind of thing is because sometimes modern historians just fall into the patterns of their ancient predecessors that interpreted their whole world from the perspective of the elite classes, and those elite classes don’t tend to think of ordinary people like soldiers as having much agency. So instead of a solution that’s the first thought of anyone who has ever been a peon, you have this really strange discourse about ways an officer might manage to count a large amount of soldiers like cattle. I guess the takeaway from that is, there’s valuable novelty and insight in that retail job you hated.

NW: It always feels a bit overly aggressive to ask an author who has just published a book: what’s next for you? I promise, I mean this in a very non-aggressive but very excited way!

KM: My next book is about the concept of Victory or Death in the ancient world. The aim is to discuss on what occasions and for what reasons soldiers have either voluntarily adopted an ethos of ‘victory or death’ or found themselves in situations where it has been thrust upon them. It’s something that sounds quite cheesy on the surface but as soon as you start to dig, it immediately turns out to be a fascinating and multi-layered topic.

The obvious example is, of course, the 300 Spartans who died at Thermopylae during the effort to repel the Persian Invasion in 480 BCE. The curious thing is that you then also find the same sort of principle occurring in a totally different situation, so for example when the 10,000 who make the march upcountry, as described in Xenophon’s Anabasis, get together and have a democratic meeting in which they decide explicitly (by vote) to march homeward and either get there or die in the attempt.

So while Inside the Roman Legions is a what and how book, carefully following the soldier through a campaign and looking and what he was doing and how it was done, Victory or Death is going to be a why book, looking at vastly different situations that share one core theme where the question is, why was this same ethos adopted by these men in different times and places? Why was that attractive or appealing, or at least preferable to the alternative?

These types of projects are always a little speculative because they are talking about someone’s thinking and motivation, things which are difficult to know even when you have a very high quality of evidence, say, a first-hand account like we have with Xenophon.

These questions are also often the most fun, though, because you can give your best guess as someone very educated in the ancient military, and you can also lay different possibilities in front of the reader for them to think through and consider for themselves. There isn’t one right answer and everyone has some experience or knowledge that can help shed a new light on what’s happening. As ever, though, my focus is ground up, thinking through what it was like to be the ordinary men in the moment.

NW: You’re been very outspoken about the difficulties of the writing process and mental health in general. What advice would you give someone who is writing a book?

KM: Don’t give up! The most important thing is to just keep working on it. You might have to accept that it will take longer than you estimated, as it almost certainly will. You will go through periods of self-doubt, where you might become very negative about your work, and, by extension, yourself.

But you are not your work, and your quality as a writer is not determined by a first draft, which is always a rudimentary, clumsy version of what it will eventually be. If you continue to follow the process, you’ll find that it is much easier to edit work than it is to generate that writing in the first place.

So you constantly have to remember that every day is just a piece of the bigger picture and the bigger project, and that what you are feeling in the moment, when no phrasing sounds right, or you’re beginning to suspect your argument might not be hitting the really important points, is only a temporary state of affairs. Your work can be bettered tomorrow and the day after that and the day after that. Problems don’t define you because they get fixed, awkwardness gets smoothed out, dubious arguments get re-written, and it all comes together eventually just as long as you can keep on working.

It’s hard to keep your self-confidence up when you’re completing such a big project, and especially so if you’re one of my people, prone to depression, anxiety and self-doubt. We’re always going to be the tortoise in the story of the tortoise and the hare. Slow and sure (or even slow and sporadic) is our strength.

The good news is that speed is rarely a virtue in writing. If writing a book is your dream but you struggle with low moods and feelings, firstly, you’re not alone, and secondly, it absolutely can be done. The most vital thing you can do is keep coming back to it, again and again and again. You’ve only failed if you actually stop permanently.