Over the next few weeks, we continue to feature the winners of this year’s Zenger Prize. What is this prize and why does it matter? See Marvin Olasky’s introduction and explanation.

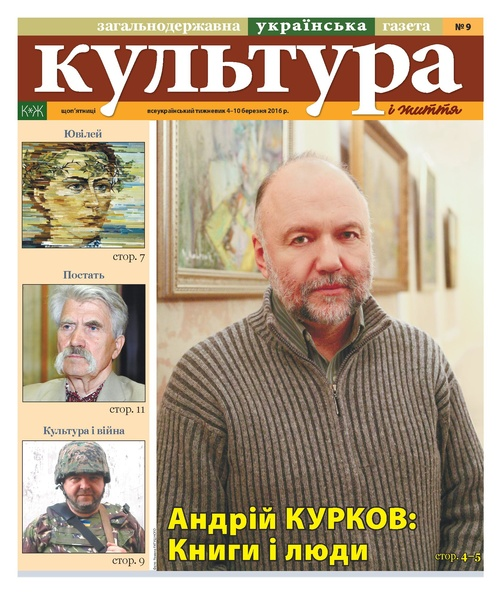

Ukrainian novelist Andrey Kurkov received 500 rejections and wrote eight novels before finally catching the attention of a Swiss publisher, who took a gamble on Kurkov’s Death and the Penguin, a satirical, surreal novel set in post-Soviet Ukraine.

The gamble paid off. That first Penguin installment has now been translated into 30 languages. “For 19 years I was sending my novels and samples in English to hundreds of publishing houses and agents,” Kurkov told me: “I’m just trying to sort out my archives, and I would say I spent a quarter of my life looking for a publisher.” He’s now published 20 novels.

It wasn’t his fiction, but his journalism for The Guardian that recently impressed Zenger Prize judges. Zenger House honored the writer for his article “The hope for ordinary Ukrainians in 2023 is the victorious return of their country—and of the light,” where judges say Kurkov used “novelistic talent to show with vivid metaphors Ukrainian life away from the front lines.”

Kurkov’s articles on the war in Ukraine maintain the grittiness of his novels but lack their characteristic humor. Once the war intensified, Kurkov said he “could not write fiction anymore.” He now writes “nonfiction essays and journalistic articles and reports trying to explain life in wartime Ukraine in a way, not from the factual point of view, but from human point of view, because I’m mostly paying attention to human stories, to people’s stories…. I know from my experience what it means to be a displaced person or to be a refugee.”

Kurkov, after writing about the deaths of two close friends, still looks for things that “provoke smiles. I’m talking about the resilience of Ukrainians, which is achieved by strange means sometimes. Ukrainians survive and don’t give up in the most difficult circumstances. For example, Ukrainians joke that the bars, especially the bars which are underground in the caves or basements, make the best bomb shelters.”

Beyond statistics and overnight developments, Kurkov said he aims to give names and faces to the effects of war: “The most sad thing about this war is that in many articles, especially abroad, the war in Ukraine consists of daily changes in statistics of the losses on both sides, losses of tanks and artillery units, et cetera. How many civilians killed, how many buildings demolished? This kind of information makes war faceless.”

From his apartment in Kyiv, Kurkov recalled the many stories that sprung from the mass exodus of civilians from Ukraine at the escalation of the conflict, saying, “half of Ukraine was escaping the war. I remember several times staying with my wife in a car in traffic jams that were 40 to 70 miles long, because all of Ukraine rushed to one and the only main road to the West.”

He believes more fodder for storytelling will result in years to come, as refugees grapple with whether to return to their homeland: “We are talking six- to eight-million Ukrainian refugees abroad… mostly women and children whose husbands are either back in Ukraine because they cannot leave or they are on the front lines, or they have been killed or wounded… I want to imagine how these families will reunite, and I cannot imagine it. [There are now] 400,000 Ukrainian kids in European schools. They are learning the languages, they’re adapting to new life in a new environment.”

Kurkov “cannot imagine that the wives, when the war is over, will take children from the schools, from their new friends, in order to come back home to the towns and cities where schools are destroyed, or schools are built now underground for safety. So this war is far from the ending, but the consequences of this war are already with us. We are living inside these consequences.”

Though Kurkov acknowledges the outcome of the conflict is far from settled, he believes the “entrepreneurial” spirit of Ukrainians will persist. When I asked him the key difference between Ukrainians and Russians, he cited history and said the main distinction is “individualism (Ukraine) versus collectivism (Russia)… For Ukrainians, freedom is more important than stability. For Russians, stability is more important than freedom.”

Despite their individualist mindsets, Kurkov said a shared sense of optimism “helps to survive…. Social optimism is based on the understanding that we are a huge community with the same faith in humanity, with the same belief that we can make life better, we can make the world better, and if the world is in danger, we can together defend the world in order not to face a real catastrophe.”

But that degree of optimism takes effort in the face of grim reality: “When I think about the last two years, I get extremely emotional because I’m one in this sea of boiling human destinies trying to settle people, trying to imagine the future, to imagine what will happen next for split families.”