“To sing is to praise God”

Last year Joan Baez released a documentary, I Am a Noise, that teases a deep dive into secrets buried within unpublicized writings and recordings. For her fans, though, the film failed to reveal anything new about her past. She talks about her struggles with anxiety, sibling rivalry, addiction, and her relationship with Bob Dylan. The most surprising revelation concerns questions about whether her parents subjected her to “abuse” when she was a child, doubts that were raised during recent hypnosis-therapy sessions that also revealed her “multiple personalities.”

The charges of abuse are shocking, especially because Baez credits her scientist father and homemaking mother with instilling in her the values of peace, love, and compassion that she used to frame her career as a folk singer and activist. She grew up in a Quaker family, traveling the world for her father’s work as an UNESCO researcher. In places like Baghdad her father taught her to see the poor as worthy of sympathy and help. Albert Baez and Joan’s mother, the elder “big” Joan, were also pacifists, one of the most salient characteristics of Quakerism. As Baez emerged as a folk queen in the early 1960s, she followed her conscience by marching for civil rights, desegregating concert venues, and committing herself to non-violence in opposition to any war. Baez’s public stance against racism and the Vietnam War were risky to her career and her personal safety. Critics dismissed her, calling her a communist, a socialist, and an ignorant hippie. She even received death threats for speaking out.

Baez may have been a hippie during the 1960s and 70s, but she never considered herself a communist or even a traditional socialist. In fact, she is difficult to label—a radical without a Marxist ideology, a cultural icon but not an intellectual. Her role on the left does not conform to the usual categories, and yet she has had a lasting impact promoting left-of-center issues of social justice. But Baez’s identity as a Quaker sums her up best, a term she has embraced in lieu of espousing firm political affiliations.

Baez, in fact, has modeled her life on the folk ballads that made her the Queen of Folk, a martyr of sorts, sacrificing herself for the sake of others, for political causes, for love, for God, and for the world. When placed within a narrative of the tragic heroine, Baez’s political and religious activism in the second half of the twentieth century makes more sense as an integrated identity: a radical folksinger who lent a religious voice to the American left as a “Quaker Maiden.”

Baez’s interest in peace and social justice intensified when she first heard the voice of Martin Luther King, Jr., the keynote speaker at the Asilomar Conference on Civil Liberties (run by the American Friends Service Committee) in February 1958. The next year Baez met Quaker Ira Sandperl, the most profound influence on her political development. Until then, Quaker meetings had been boring to young Baez, but the bearded man talking about peace caught her attention. Soon the two began making appearances together—Sandperl speaking and Baez singing. Even at a young age Baez was considered “an expert on anything political.” She chalked that up to her Quaker education. “It wasn’t that I knew so much but rather that I was involved,” she explained. “And the family attended Quaker work camps where I heard about alternatives to violence.”

At core, Baez’s regard for human values and the sincerity of her pathos resonate most of all, serving as the crucial link between her music, religion, and political activism. She is the very model of the tragic heroines and heroes who figure so predominantly in her catalog: “Barbara Allen,” “Silver Dagger,” “All My Trials,” “Joe Hill,” “Sweet Sir Galahad.” Baez has made it her signature to sing about lost love and lost causes, heartbreak, and sacrifice. “Barbara Allen,” for example, tells of an unrequited love that lingers into death, while the cause of executed labor leader Joe Hill transcends death.

Notably, her religious outlook dovetails seamlessly with her veneration of tragic folk heroes. Quakers, like Baez’s musical martyrs, tend to pursue seemingly impossible causes. They believe in achieving world peace, and the abolition of war, poverty, and hunger. They believe that every individual is a sacred vessel of God, deserving perfect equality. And they believe in the power of love and nonviolence to overcome all obstacles—that good, ultimately, will prevail over evil.

Baez’s activism developed in tandem with her singing, a career launched at the 1959 Newport Folk Festival. From the start she utilized her fame to carry a message to the masses and to comfort the afflicted. “I preached a tiny bit more in each concert,” she said, “and in the dressing room afterwards was treated as a kind of sage, usually speaking of nonviolence and Gandhi.” She organized with civil rights activists, beginning in 1962; performed at the 1963 March on Washington; stood beside Chavez’s Migrant Workers; and marched with King in Grenada, MS and Selma, AL. She also went to jail for encouraging draft resistance during the Vietnam War.

As she put it in her 1987 memoir, she considers her voice a divine gift for “the betterment of humankind, in the service of God.” “To sing is to praise God,” she wrote in 1968. For Baez, performing is also a way to inspire her audiences to practice the gospel’s abiding truth that “Greater love has no one than this: to lay down one’s life for one’s friends.” Since the 1960s Baez has often put herself in harm’s way for the sake of political causes, as when she traveled to Hanoi in 1972 amidst U.S. bombings, or when she appeared in Sarajevo in 1993 to hearten war-torn Bosnia. Václav Havel even referred to her 1989 concert in Czechoslovakia as a turning point in his country’s Velvet Revolution. Her condemnation of human rights abuses also put her in a vulnerable position while touring Latin American nations such as Argentina, Chile, and Brazil in the early 1980s, when she received death threats upon her life. She has used the stage as her pulpit.

Baez has received as many accolades and awards for her activism as for her music. Just a partial list is impressive: the Jefferson Award (American Institute of Public Service), Thomas Merton Award, Earl Warren Civil Liberties Award (ACLU), Americans For Democratic Action Award, SANE Education Fund Peace Award, Distinguished Leadership Award (Legal Community Against Violence), Humanitarian Award (Children’s Health Fund), and the Amnesty International Ambassador of Conscience Award, as well as the two honorary degrees in Humane Letters from Antioch and Rutgers Universities.

The so-called “Queen of Folk” is clearly a significant political force around the world, and in this time of recurring despair and small victories she remains relevant as a gallant siren, not a “noise,” as this latest documentary has it. The Quaker Maiden continues to warn us of danger and call us to action.

Vaneesa Cook received her PhD in US history from UW-Madison and is currently a historian at UW- Madison for the Missing in Action Project. Her book Spiritual Socialists: Religion and the American Left was published by University of Pennsylvania Press in 2019 and was released in paperback in March 2023.

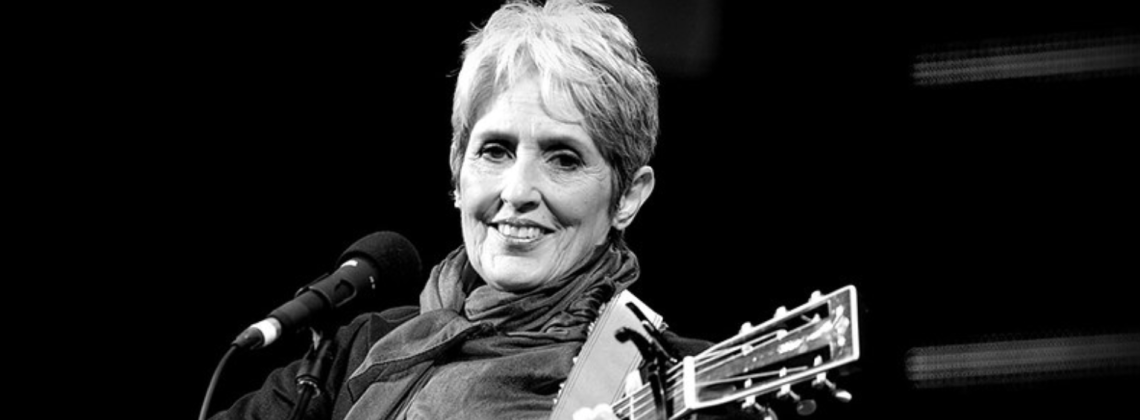

Photo credit: @streetlevel