In Tara Isabella Burton’s new novel, fancy, fantasy, and possibility all point in one direction: home

In defending the value of book reviews a year ago, Current Contributing Editor Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn wrote, “The life of the mind—and the heart and soul—leaves traces. Our place of entry into cultural life falls somewhere in-between the pen strokes of some and the brushstrokes of others: Our voices soar or tremble amid the echoes of the spoken words of some and the still resounding music of others. One of the strongest cases for the reviewing of books is that it is a way to participate in this tradition of commenting on the ideas and creations of others, a tradition with ancient antecedents.” This week, in Current’s first ever Spring Books Week, we take a break from regular features to listen to this music and participate in this ancient tradition.

*

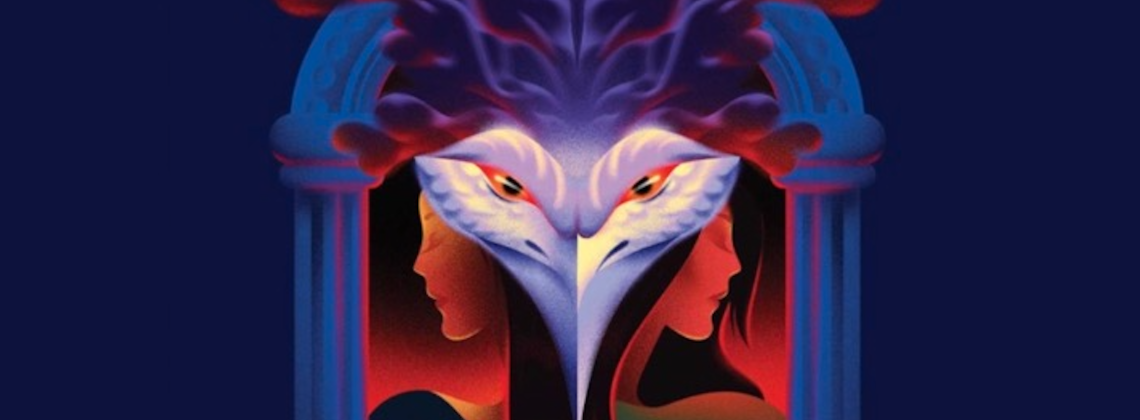

Here in Avalon by Tara Isabella Burton. Simon & Schuster, 2024. 320 pp., $28.99

When you interpret, teach, and write about fiction for a living, it is a little bit harder to fall under its spell. Until you do—and then you don’t want the spell to end. The novel lover’s eternal conundrum.

It didn’t help that I started reading Tara Isabella Burton’s Here in Avalon during the grading season, when professors will do anything to avoid reading papers that start with sentences like: “Death is commonly thought of as a detriment to life.” Indeed. Also a bit ironic, given that Here in Avalon is about people who are dead inside, longing for life.

Two very different sisters, Cecilia and Rose, live in New York City. Cecilia, the more fanciful of the two, chafes against the mundane, longing for something more, something she cannot find or even name. Naturally, when a mysterious stranger invites her to a floating cabaret aboard the Avalon, she accepts. The invitation comes only to the lost denizens of the city, who work meaningless jobs during the day and frequent lonely bars at night, knowing that this can’t be all there is. It is then they are handed a card that reads: Another life is possible.

That another life is possible is, of course, both true and false. All artists know the paradox, and it’s exactly what makes this novel so very, very delicious. “I dwell in Possibility” writes Emily Dickinson, “A fairer House than Prose.” What Dickinson means by “prose” is the prosaic. Most of us live lives of quiet desperation because we are unable to imagine something different. In response, the mysterious Avalon (an Arthurian reference; a Celtic word meaning paradise), with its moonlit, champagne-filled dances and its hauntingly beautiful music, enchants with possibility.

Rose, frantically trying to find Cecilia, figures out where she went and manages to get an invitation to the Avalon herself. When she first steps aboard, she hears a song that moves her in a way she cannot explain. She later discovers that it had been written only for her, played once, never to be played again. The narrator divulges:

Years later, when Rose tries—as she so often will—to tell the story of the Avalon, she will be able to describe so much. She will be able to describe the beading on Jenny’s orange dress, and the way the changing colors of the flame make Rebecca look as if she were made of glass. She will be able to describe, as accurately as she can remember, the layout of the boat—though the size will always vary in her telling—where the pillows lay on the divan and where stood the little wooden tables, carved into the shapes of elephants and giraffes. But she will never be able to explain, not to her satisfaction, what it was about that song that turned her inside out.

The Avalon’s intensely personal invitation is classically erotic. Rose experiences what the sociologist Hartmut Rosa calls resonance. It is the perfect word for an experience that happens in the body as well as the soul. The listener feels it in her bones and in her gut. “If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry,” wrote Emily Dickinson.

Thus the Avalon is a metaphor for (among other things) all the arts. It is the arts that fire our imagination and suggest that a more enchanted life is possible. We just have to find the community of others who finally get it. But the catch is, as Rosa explains, that although resonance can be experienced at any time—in the surprise of the year’s first snowfall or the fourteenth time you hear Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1 in G Major, it cannot be produced on command. In a world that falsely promises us total control, that’s the rub.

Consider one of the most painfully true poems about art ever written, Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” The speaker, gazing at the figures on the urn, asks:

What men or gods are these? What maidens loth?

What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape?

What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?

And then decides:

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on;

Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear’d,

Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone:

Fair youth, beneath the trees, thou canst not leave

Thy song, nor ever can those trees be bare;

Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss,

Though winning near the goal yet, do not grieve;

She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss,

For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair!

All artists understand that unheard melodies are sweeter than heard ones. The life of perfect harmony with yourself and others lies tantalizingly just beyond reach. While this fact frustrates the artist, it can destroy anyone who tries somehow to freeze life during these resonant moments. The melody made exclusively for you, the one with which your soul will eternally vibrate, cannot take shape, for as soon as it does, it is already in the process of dying away. The moment you kiss your lover, the kiss—and your lover—are already losing their allure.

It’s too much for most of us to take, so we stop imagining. The arts seduce us with the promise of another life, but our experience of them always ends the same way: consigned to this life. The endless possibilities of youth fade into the well-worn paths of age. An ancient and sad story to be sure. So is Here in Avalon yet another Romantic tease?

No. The brilliance of this novel is that it powerfully resists the either/or of fantasy escape vs. real life. Burton opens with a letter to the reader: “Here in Avalon is a love letter to cults. Or more accurately it’s a love letter to my cults: to the bizarre, maddening, and often wonderful groups of people who throughout my twenties and into my thirties have taken me out of the worlds I thought I knew, made me question who I thought I was, and challenged me to reimagine what I wanted.” Those “cults” include an idealistic group that re-creates costume balls in Italian cities out of a “shared desire to exist in a realm of beauty and poetry outside real life,” and the Bruderhof, the pacifist Christian commune Burton found herself “hungering to join” during a difficult time in her life. The tagline another life is possible is the Bruderhof’s.

If you are not in a book club, start one immediately—and debut it with this novel. If together you can figure out why Burton says it’s ultimately “a story about coming home,” you’ll be on your way to the richest of all delights. Because the novel’s tremendous power comes not from the seduction of escape, but from the truth that another life is possible—inside of this one. It was no surprise to me that the novel references St. Ignatius of Loyola, whose ability to imagine that other, more spiritually resonant life created an entire order and a group of spiritual exercises that have helped countless people to see it. When Rose confronts a member of the Avalon community by saying, “I don’t know how you can stand it . . . knowing it’s all a lie,” the text reads:

“Everything’s a lie,” Cassidy said. “You just have to choose the kind of lie you can live with. Do you know what Saint Ignatius of Loyola used to say?”

“What?”

“Perform the acts of faith,” he said, “and the faith will come.”

Burton’s novel proves that Cassidy has misunderstood Loyola’s words. Performing actions in love lead to faith because God is love, not because believing in God is a healthy lie. Ignatius of Loyola taught that another life is possible, but it starts in the most mysterious and unreachable place of all—between your ears, in this present moment, and through your irreducibly particular body. Because true freedom lies in our decision of what to pay attention to and how to respond to what happens to us.

The possibility of another life only starts there, though. What keeps it from being a fantasy is that it doesn’t end there. It continues into the next step taken, and then the next, and the next. Those steps continue into what becomes a journey, and they end at one destination: the one at which you chose to point your feet. Home.

Christina Bieber Lake is Professor of English at Wheaton College, and the author of Beyond the Story: American Literary Fiction and the Limits of Materialism. She is a Contributing Editor for Current.