In his book Philosophy 101 By Socrates, philosophy professor Peter Kreeft writes, “One advantage of being a philosopher rather than a soldier or an economist or a lawyer or a doctor is that you have job security even after death. It makes little sense to hope for a heaven that contains soldiers (that is, wars), economists (that is, poverty), lawyers (that is, injustice), or doctors (that is, disease). But philosophers, artists, musicians—they are even now doing heavenly things.” Traditionally Christians call the Good, the True, and the Beautiful the three “transcendentals.” These are the principal features of heaven and of God himself.

Scripture gives evidence of this. Psalm 19 begins, “To the chief Musician, A Psalm of David. The heavens declare the glory of God; and the firmament sheweth his handywork” (KJV). Those of us in liturgical churches may find ourselves singing the Sanctus each week, which is based on Scripture in Isaiah (Chapter 6) and Revelation (Chapter 4) in which heavenly hosts sing the praises of God: “Holy, holy, holy, is the Lord of hosts: the whole earth is full of his glory.” We have references to representational art, such as God is the potter, we are his clay (Isaiah 64: 8) Take the notion of creativity itself, perhaps most evocatively at the beginning on John’s Gospel in which creation and speech are intertwined: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” (John 1:1, KJV). This is an echo from Genesis in which God speaks the world into creation. J.R.R. Tolkien notably drew from this tradition in making his own creation story for his Middle Earth mythos. In Tolkien, God (Ilúvatar) along with his angels (the Valar) sing creation into existence. Song is therefore important as it is an attempt at bringing to the forefront the poetry that underlies all of existence.

Entire biblical books such as Psalms and Song of Songs are poetry easily set to music. Regarding philosophy, there are many references to wisdom in scripture (e.g., Job 12:12: “With the ancient is wisdom; and in length of days understanding.”). Catholics and Orthodox include the Book of Wisdom in their Bible. Overall, look at Philippians 4:8: “Finally, brethren, whatsoever things are true, whatsoever things are honest, whatsoever things are just, whatsoever things are pure, whatsoever things are lovely, whatsoever things of good report; if there be any virtue, and if there be any praise, think on these things.”

This verse from Philippians and Kreeft’s observation should inform how we educate, especially for institutions that claim to be Christian. No one contends that we don’t need soldiers, economists, lawyers, or doctors. But those are professions tied to the temporal order, arising because of the Fall and the worldly deficiencies that follow. If a school places the salvation of souls as a central part of its mission, then it needs to immerse its students in the humanities and fine arts. This should be the primary task of the school, with education in worldly matters an important secondary task. The humanities and fine arts provide us with ears to hear and eyes to see the Word of God that is at the heart of creation. They also give us a foretaste of heaven. We are already training for that which we (God willing) will be doing for all of eternity, namely giving glory to God while dwelling in his goodness, truth, and beauty.

Christian Wiman makes a similar point in his new book, Zero at the Bone. He quotes French philosopher Michel Henry saying, “At its outset, all art is sacred, and its sole concern is the supernatural. This means it is concerned with life—not with the visible but the invisible.” Art exists precisely because there is more to reality than meets the eye. We need art—broadly defined—to give us a true picture of the world. If there is no more to life than what meets the eye, why would we need art? We would describe things as Mr. Gradgrind does a horse in Dickens’s Hard Times, by referring merely to its physiology. Yet, if all we know about horses are the raw physical details, do we really know horses? Or is there something poetic about horses? Some truths about horses (or anything else in the world) can only be captured via artistic representation. For example, to genuinely know horses wouldn’t you want to hear a veteran horseman tell stories about how horses act? Perhaps there is higher knowledge about horses in the Henry Herbert Nibbs poem “The Walking Man” (which I learned from listening to Waddie Mitchell), knowledge you could never learn from a purely scientific study of horses.

Lots of schools give lip service to the humanities and liberal arts. My own institution does so in its “Mission, Vision, and Values” statement. But don’t listen to the vain words. Schools demonstrate their educational priorities through curricular and staffing decisions. If a school’s curriculum is light on the liberal arts, that tells you something about how they view the human person. Institutions that are cutting the humanities and fine arts–dumbing down the curriculum, eliminating programs, and cutting faculty lines in those areas–do not value the humanities/fine arts, no matter what happy words they throw at you. Christian schools (K-12 or higher education) that care more about SAT/ACT scores or career prep and job placement than introducing their students to beautiful art and beautiful, true ideas are telling you they don’t really care about their students’ souls, no matter the school’s mission statement or fancy Latin motto.

I know people who support “Christian education” but think all that literature, poetry, and art stuff is a bunch of sissy crap. I mean, how will that help you get a job? When are you ever going to use that? Kreeft, Wiman, and Scripture tell us when you are going to use it. In heaven. When you need it the most.

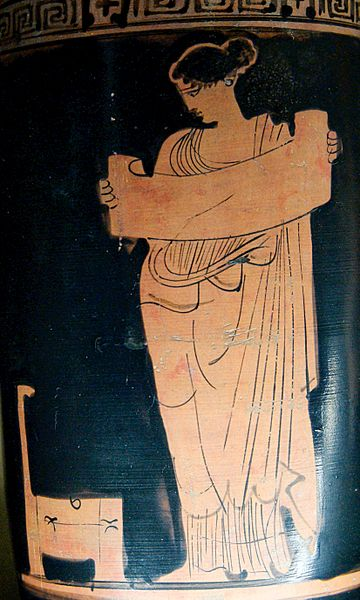

Image: Attic red-figure lekythos, Boeotia, c. 430 BC. Public domain.