A prophetic meditation on the banality of idolatry

A Web of Our Own Making: The Nature of Digital Formation by Antón Barba-Kay. Cambridge University Press, 2023. 306pp., $29.99 (paperback)

Many of my students believe that digital technology is basically neutral. Sure, the digital landscape has made it exceptionally easy to bully someone, sow disinformation, or advance harmful ideologies. But, they are quick to say, we can also leverage this same technology to lift up historically silenced voices, pursue justice, and express genuine care by crowdsourcing material support for those in need. Today’s technology can equally agitate or soothe. It can help you feel loved or leave you feeling lonely. In sum, it just depends on how you use it. And, if we’re being honest (my more pragmatic students confide), despite whatever social ills may be rooted in the digital, it’s a technology that provides daily conveniences and pleasures that we’d simply rather not do without. Besides, it’s not as if we can turn back the clock and just stop using technology. It’s integral to the world we live in now, so we just have to deal with it.

When I encounter this stance on technology year after year, I tend to grow depressed. It reminds of the opening scenes of The Matrix, where Neo is going about living his dreary life working in a cubicle, vaguely pursuing relief through his computer hacking, drifting through spells of desperation amidst the incoming tides of everyday human existence. It’s just how life is, he thinks . . . until Morpheus shows up. Morpheus tells him that there is in fact more to life and offers Neo a choice: He can take the blue pill and return forgetfully to his previous existence, so dissatisfying but safe, or he can take the red pill and have his eyes opened to see the actual Reality. Neo opts for the red pill and goes careening down a wild journey of mind-bending revelation that initiates him into the nature of Reality and empowers him to live with newfound purpose.

If you are like my students but also know deep-down that you are the red-pill-taking type, read Antón Barba-Kay’s A Web of Our Own Making and be prepared for a ruthless unmasking of what our digital technology is really doing to us.

Barba-Kay begins the journey by sketching out an all-too-familiar perplexity of the internet and our times—put simply, you can’t live with it and you can’t live without it. If we are willing, however, he is prepared to lead us on a full-throated investigation into the existential meaning of our particular digital moment. But we’d better buckle up because this bruising philosophical examination is not for the faint-hearted, nor does Barba-Kay suffer fools gladly.

In fact, he doesn’t seem to suffer sages either. He expresses dismay at the critics of digital technology (whom he otherwise admires)—Nicholas Carr, Jaron Lanier and the like—who manage to end their treatises on “a note of contrived and desperate positivity” about the future of humanity in a world tangled up in the digital juggernaut. He finds their conclusions to be “anemic” against the full weight of the problems they have articulated, “as if one could tame the whirlwind by politely requesting that it shift its trajectory a little to the left.” Writing with verve, Barba-Kay is relentless in his honesty about our primal tendencies as human beings. He takes us by the collar and thrusts us right up to the edge to stare unflinchingly into the troubled abyss of technology and human nature.

In the first half of the book, Barba-Kay introduces his understanding of technology as both forming our sensory perceptions of reality and materially manifesting society’s unexamined values and visions of the good life. His sweeping observations on how technologies function to phenomenologically shape our ways of knowing are reminiscent of Marshall McLuhan, Walter Ong, Harold Innis, and Jacques Ellul. Working within this tradition of medium theory, he familiarly contrasts the cumulative and enduring qualities of knowledge when transmitted via writing and printing to the immediacy and evanescence of digital information. But what distinguishes Barba-Kay’s stance is his chilling observation that digital technology is the first to be aesthetically felt and understood as “natural.” It is, he argues, a system that can so efficiently data-analyze and quantify the realm of our qualitative experiences that it satisfies us with the sense of having all our desires and hopes “engaged, activated, met and answered.”

Unlike most critics who might be simply predisposed to dislike industrialization’s colonizing drive to quantify all that is qualitative, Barba-Kay steps out further and points out digital quantification’s superpower: its ability to appear value-free and neutral. This renders its formative and ethically consequential effects invisible to us. Like the technology of the mirror, he argues, digital technology presents a likeness of our reality that seems so utterly accurate that we simply take it for granted as reality itself. He writes,

. . . the more digital technology is capable of anticipating and accommodating our desires the harder it is to keep it in view, the greater its formative power, the more it looks just natural or intuitive to us. What’s “natural” is, in this sense, the highest achievement of contrivance. Just as mirrors are themselves invisible, digital technology sinks in by covering its own tracks.

Like a mirror into which we cannot resist gazing, digital technology gives us such powers to measure, manipulate, and control that we simply can’t help but identify its powers and criteria as authoritative in “our own conception of what is true, who we are, and what is good,” Barba-Kay laments.

As a result, we tend to willingly ignore digital technology’s simulacra and mediating presence, and we allow ourselves to be drawn in and disarmed. We take and we consume, thinking nothing is happening. The problem: Everything is happening. Algorithms are ceaselessly churning out predictions of what will satisfy us next. Our data are being ceaselessly collected and then employed to tighten our leash to platforms and devices ever more. Hundreds, even thousands of years of civilizational institutions premised on the limitations and inefficiencies that have long characterized corporeal human existence and the demands of finding ways to live together are swiftly eroding, giving way instead to the supreme efficiencies of code. In the process, if we are unbound by the limitations of time, space, and creaturely finitude, we may bypass the opportunity to cultivate such second-order goods as patience, perseverance, grace, and humility.

Because we fail to recognize how everything is happening, Barba-Kay warns that our contemporary digital ecology is fundamentally dis-integrating and dehumanizing. It is dis-integrating our liberal democracies because the key ingredients for citizenry no longer exist in today’s online environment: We are freed from the accountability of our bodies, freed to pursue and build our own individualized cultures, and freed from the bothersome inconveniences that used to require us to ask for directions, walk over to talk to our colleague or neighbor, go to the store, wait one more day. The democratic project itself becomes increasingly untenable as the constraints of everyday life that have long trained us in the common social ethics and art of neighborliness are diminishing with the total responsiveness of today’s technology.

Beyond the uncertain future of longstanding institutions, Barba-Kay is also concerned about the kind of people we are becoming. He worries that we have become routinized in the “desire to be disburdened, to be involved in the search for hacks, cheat codes, walkthroughs, multitasking shortcuts, abbreviated instruction manuals, frictionless ease.” We have become so acquainted with eluding drudgery, or even any form of unwelcome demand for effort, that we get “caught up in a way of doing things that we don’t understand because we don’t need to, since understanding is itself a hassle of which we’ve been relieved.” In this way, our digital world dehumanizes us by recklessly constructing a felt quality of existence that promises us freedom from the friction of “the dull, the painful, the difficult.” The trouble is, when we increasingly evade the very features of the human condition that our forebears have otherwise been forced to confront, we forego a confronting that actually opens us up to discover what makes a life worth living.

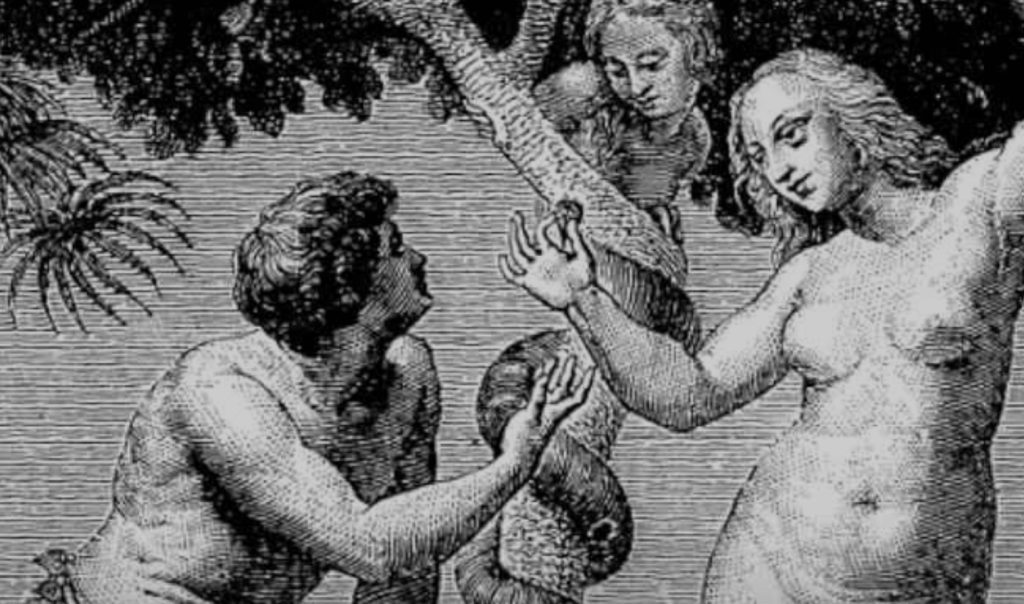

Like a haunting echo of Hannah Arendt’s notion of the banality of evil, Barba-Kay presses hard into this curious banality of our digital world’s capacity to thoroughly indulge us in “the commonplace seductions of what we know to be smaller satisfactions.” Such is the plight of our modern idolatry. Like the people of Israel who worshiped their self-made golden calf when the God who liberated them from slavery was present but seemingly inert and mute, we too are prone to choose the lesser satisfactions found in our self-made technological world over the realities that we know deep down to be richer and more meaningful—and ultimately, more true.

Like the God of Israel, the problem with Reality, Barba-Kay points out, is that it cannot be tamed. We are vulnerable to its whims. And so, in our fear, we prefer the security of control and protection—even if it is ultimately a fiction. However, what has turned upside down in our current technological moment is the extent to which Reality is no longer the “neutral, descriptive term—not something that was there all along—but an aesthetic category of experience as it exists now in specific contrast to life online.” In fact, because we can be so thoroughly cocooned in the bubble-wrap of our technological world, the “friction” of Reality feels now simply like another lifestyle choice. Reality is now “an ‘experience’ artificially and perversely chosen for its own sake”—like camping or homesteading!

Writers in the Marxist and/or postmodern veins, like Herbert Marcuse, Guy DeBord, Zygmunt Bauman or Jean Baudrillard, would point out that the ideologies of industrialized and consumer capitalism have long persuaded us to prefer the comforts of fiction over the harshness of reality. Barba-Kay highlights, by contrast, how today’s technological systems amplify and concretize the plausibility structures of this way of being.

One of his most poignant observations concerns the nature of the threat of artificial intelligence and robotics. It is not that humans will “lose” to autonomous technologies that will “learn to do without us.” Rather, he despairs, the danger is rooted in the kryptonite of our human nature: “that we will unlearn how to be without them.” He writes that the real threat lies in how “we will increasingly rely on and train ourselves to work with or alongside them, such that they will come to be that in terms of which we understand ourselves—our most important mirrors.”

When we consider how much our imaginations about what is “natural” have changed through human history, and when we consider how fluid our understandings of what it means to be human actually are, and when we consider how easily we forego our dignity and rights when given the options of full bellies, comfortable lifestyles, and protection from harm, the sobering assessments Barba-Kay lays out deserve many deep sighs and at least a few sleepless nights. Like a fever dream, A Web of our Own Making works on the reader in fits and starts, circling in and swooping down on the fact that the key threat to today’s technology lies in our own selves. In this way, he delivers a strong dose of tough love—a prophetic word that may not be welcomed, but very much needs to be heard.

Felicia Wu Song is Professor of Sociology at Westmont College. She is the author of Restless Devices: Recovering Personhood, Presence, and Place in the Digital Age.