I published this piece at Common-Place, back in 2008. I thought I would repost it for Valentine’s Day:

Can Presbyterians fall in love? Okay, everyone falls in love, but when people think of Presbyterians they normally conjure up images of stoic Protestants whose kids eat oatmeal and memorize the Westminster Confession of Faith. Reverend Maclean, the Montana minister and father figure played by Tom Skerritt in A River Runs Through It, comes to mind. Presbyterians don’t “fall” in love—they rationally, and with good sense, ease themselves into it.

This was my image of Presbyterians until I read the correspondence of Philip Vickers Fithian. Most early American historians know Philip Vickers Fithian. He was the uptight young Presbyterian who served a year (1773-1774) as a tutor at Nomini Hall, the Virginia plantation of Robert Carter, and wrote a magnificently detailed diary about his experience. For most of us, Fithian is valued for his skills as an observer. His journal offers one of our best glimpses into plantation life in the Old Dominion on the eve of the American Revolution.

But despite Fithian’s ubiquitous presence in the indexes and footnotes of contemporary works of Virginia scholarship, most of us know little more about him than the very barest facts: He was born in 1747 in the southern New Jersey town of Greenwich. He was the eldest son of Presbyterian farmers but left the agricultural life in 1770 to attend the College of New Jersey at Princeton. After college he worked for a year on Carter’s plantation and was ordained to the Presbyterian ministry. In 1776 he headed off to New York to serve as a chaplain with a New Jersey militia unit in the American War for Independence.

Such chronicling—the stuff of encyclopedia entries and biographical dictionaries—only scratches the surface of Philip’s life. It fails to acknowledge the inner man, the prolific writer who used words—letters and diary entries mostly—to make peace with the ideas that warred for his soul. Philip was a man of passion raised in a Presbyterian world of order. He came of age at a time when Presbyterians were rejecting the pious enthusiasm of the Great Awakening for a common-sense view of Christianity. And while Philip was clearly a student of this newer rational and moderate Protestantism, he remained unquestionably Presbyterian. For he was a man stretched between worlds: one of cautious belief, another of passion and sentiment; one of rational learning, another of devotion and deep emotion. His struggle to bring these worlds together is seen most clearly not in his well-known observations of plantation life but in his letters to the woman he loved—Elizabeth Beatty.

Philip first met Elizabeth “Betsy” Beatty in the spring of 1770 when she visited the southern New Jersey town of Deerfield to attend her sister Mary’s wedding to Enoch Green, the local Presbyterian minister. It may not have been love at first site, but it was close. Philip was enrolled in Green’s preparatory academy, and Betsy was the daughter of Charles Beatty, the minister of the Presbyterian church of Neshaminy, Pennsylvania, and one of the colonies’ most respected clergymen.

Betsy did not reply to this letter, and Philip’s obsession waned as he headed off to college in the fall of 1770. While he was there Philip had more than one opportunity to see Betsy again. He joined fellow classmates on weekend excursions to visit Charles Beatty’s church at Neshaminy, and it was during these visits that he made his first serious attempts to court Betsy. Though Philip and Betsy would spend much time together over the course of the next several years, the establishment of a correspondence was equally important to the development of their relationship. Betsy had given Philip permission to write her, a clear sign that she approved of his desire to move the friendship forward. By February 1772 he was signing his letters with the name “Philander” (“loving Friend”), an obvious indicator of his affection for his new correspondent.

Though much of Philip and Betsy’s courtship was conducted through letters, the exchange of sentiments usually flowed in only one direction. Perhaps Betsy did not like to write. Perhaps she preferred more intimate encounters or feared the lack of privacy inherent in letter writing. Or perhaps she did not want to encourage her suitor with a reply. Whatever the case, women generally did not write as much as men, especially when it came to love and courtship letters. In other words, Betsy may simply have been following the conventions of her day.

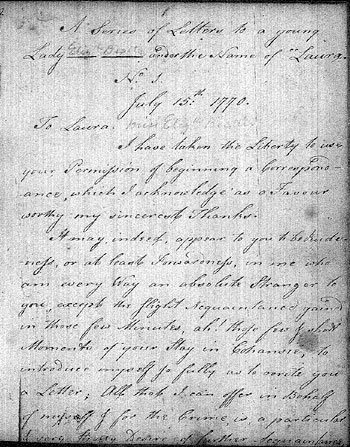

By summer 1772 Philip’s visits to Neshaminy became more frequent and his letters became more sentimental. He now began to address Betsy as “Laura” (a probable reference to Petrarch’s devotion to Laura), a name of affection that he would use for the rest of his life, and he now felt comfortable sharing the daydreams that distracted him from his studies at Princeton. “I lead you by the Hand in a cool bright Evening, & once more, in that lovely garden oh! in that pleasant, pleasant Garden, hold Conversation in Rapture with you!

Betsy was a new face in Deerfield, a fact that made her especially enchanting to the town’s young men. Philip had spent enough time with Betsy while she was visiting to begin a friendly correspondence with her. In his first letter, written shortly after she returned to Neshaminy, Philip wrote, “You can scarcely conceive . . . how melancholy, Spiritless, & forsaken you left Several when you left Deerfield!” He hoped for a prominent place “in this gloomy Row of the disappointed.” Since Betsy had departed Deerfield he could not “walk nor read, nor talk, nor ride, nor sleep, nor live, with any Stomach!” The “transient golden Minutes” they had spent together, he added, “only fully persuaded me how much real Happiness may be had in your Society.” Philip was smitten.

Read the rest here. Or dig even deeper into this story here: