The Art of Living is an occasional series about people who seemed to know something about living.

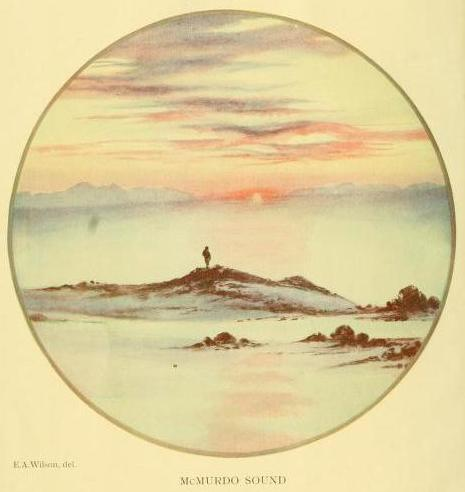

Robert Falcon Scott’s 1912 expedition to the South Pole could not, ultimately, be considered a success. He reached the Pole, but he found Norway’s flag when he got there. Roald Amundsen beat him by just over a month. The Amundsen expedition as relatively smooth, but everyone on the Scott expedition suffered from extreme challenges. Scott and four others perished on their return journey from the pole to their base. One man, Apsley Cherry-Garrard, wrote a book about the experience entitled The Worst Journey in the World. And yet. There was something about that Scott expedition and the men who were part of it that has caused them to be remembered and respected for over 100 years.

Clearly, anyone who signed up for a 1912 polar expedition had some courage. People still love to rave about Shackleton’s advertisement for the Endurance journey a few years later: “Men wanted for hazardous journey. Low wages, bitter cold, long hours of complete darkness. Safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in event of success.” Usually someone quotes that and then says something about “people today” and how inferior we are. Fair enough. But Scott not only had men seeking adventure, he had some paying to join him on his dangerous mission. It’s hard to believe.

Going to Antarctica at all required a great deal of courage. Scott had a plan for reaching the Pole, but it was untested. Scientists had determined the amount of food everyone would need and rations were carefully measured, but everything was being trialed in real time. They took ponies and relatively few sled dogs. They planned to pull sledges themselves. The ship which took Scott’s expedition to Antarctica dropped them off. There was no escape route until the ship returned. And everywhere the men encountered the hazards of Antarctica. They faced blizzards, snow blindness, scurvy, frostbite, long periods of darkness, and much more. At the very beginning, while they were on the coast, killer whales even tried to eat them. Humans love to feel like apex predators, but certainly that was not a readily available feeling to anyone on the mission. It required courage to go and courage to stick it out.

The Worst Journey in the World is a fascinating narrative of the British Antarctic Expedition, but it is also practically a handbook for Stoicism. Cherry-Garrard drew on his own diary and memories, but he incorporated diary accounts from many of the men, including some of the dead. Across the various records, it seems that throughout what truly seems to have been “the worst journey in the world,” the men endeavored to keep a stiff upper lip. They avoided complaining as much as they could. They contained their negative emotions. They tried to be cheery as much as possible. Cherry-Garrard wrote: “We were about as bad as men could be and do good travelling: but I never heard a word of complaint, nor, I believe, an oath, and I saw self-sacrifice standing every test.” This was the standard. Examples abound.

Apsley Cherry-Garrard was part of the “Winter Journey” during the British Antarctic Expedition. He and two other men traveled a great distance, in the dark, pulling sledges, in order to collect some eggs of the Emperor Penguin, for science. At many moments, it seemed that they could not survive. Yet Cherry-Garrard wrote of his two companions: “Through all these days, and those which were to follow, the worst I suppose in their dark severity that men have ever come through alive, no single hasty or angry word passed their lips. When, later, we were sure, so far as we can be sure of anything, that we must die, they were cheerful, and so far as I can judge their songs and cheery words were quite unforced. Nor were they ever flurried, though always as quick as the conditions would allow in moments of emergency. It is hard that often such men must go first when others far less worthy remain.” So they carried on, falling into crevasses and pulling each other out, sometimes dragging their sledges only three miles in twelve hours, running low on food, Cherry-Garrard nearly blind because he could not wear his glasses in the conditions, losing part of the stove they used to cook their food, and remaining level-headed.

The men who died displayed Stoicism, as well. They, too, refused to complain. One was heard to grind his teeth in pain, but the men typically remained as cheery as they could. In his journal, Scott recounted: “Should this be found I want these facts recorded. Oates’ last thoughts were of his Mother, but immediately before he took pride in thinking that his regiment would be pleased with the bold way in which he met his death. We can testify to his bravery. He has borne intense suffering for weeks without complaint, and to the very last was able and willing to discuss outside subjects. He did not – would not – give up hope to the very end. He was a brave soul. This was the end. He slept through the night before last, hoping not to wake; but he woke in the morning – yesterday. It was blowing a blizzard. He said, ‘I am just going outside and may be some time.’ He went out into the blizzard and we have not seen him since.” He went out knowingly to his death. He suffered pain and slow starvation for weeks. But, he could “discuss outside subjects” to the end!

The men of the expedition may even have taken Stoicism a bit too far. In a diary entry, Lashly wrote: “I started to move Mr Evans this morning, but he completely collapsed and fainted away. Crean was very upset and almost cried, but I told him it was no good to create a scene but put up a bold front and try to assist.” At the time, the three men were absolutely alone for dozens of miles. Evans was unconscious. Who would witness a “scene?” Even the penguins were far away at that point. In many places, in many of the men’s journals, they recall being thankful that their companions were not great complainers. A psychologist of today might not appreciate the men’s relationship with their emotions, but their approach saw them through.

It was not only Stoicism that saw them through. The men of the expedition had interests and abilities and were curious about life. They sang songs together, they played music, they recited poetry. Cherry-Garrard wrote about how they kept themselves going “…with ready words of sympathy for frost-bitten feet: with generous smiles for poor jests: with suggestions of happy beds to come. We did not forget the Please and Thank Yous, which means much in such circumstances, and all the little links with decent civilization which we could still keep going.” They read and exchanged books and then exchanged again and reread those books. They sketched. They took thermometer readings. They wrote letters to send home. They had a lecture series. Antarctica was barren, their minds were anything but.

Many are the men and women with ready complaints and overreactions for the present-day (myself among them), but we can learn something from these men from the past, who undertook The Worst Journey in the World. They stifled some of their emotions, but they did not give up their civility or their poetry or their curiosity. They understood the value of cheerfulness. In a very discouraging place, they encouraged each other. Cherry-Garrard believed that some of the men “set a fashion of hard work without any thought of personal gain.” And they were persistent in their care for others. They tended frostbite, they shared their last biscuits, they did not abandon the dying. When Scott and four others had clearly perished, a search party went to find their resting place and collect their journals and letters and observations—at great personal risk. People love to rhapsodize about Shackleton’s call to arms and about old-time adventurers, in general, but it takes a great deal more than high cold tolerance to see an Arctic journey through. It takes curiosity, courage, compassion, and self-control. And you still might not see it through. The Scott Expedition is a great example of equanimity and excellence for people in challenging times.

p.s. You can read Scott’s expedition journals and letters here.

I think it is too subtle for many Americans, but the British have a category of “heroic failure” and they delight in honoring those who populate it. Scott is a prime example – General Gordon is another, as is “the miracle of Dunkirk”.