“The Trump Debate is Dead,” Bonnie Kristian stated in her recent Christianity Today article, just a few days before the Iowa caucuses, and anticipating correctly what we saw indeed materialize at the Iowa caucuses earlier this week. People came to the caucuses not looking to be convinced, but knowing exactly who Trump was and determined to support him. Many of these supporters, after all, have now had eight years of getting used to this candidate. As my favorite American historian summarized it here at the Arena on Tuesday, “The Iowa caucuses told us what we already know.”

But here’s a thing that I find curious: Since coming to Christ in 2011, I’ve happily been a member of three conservative evangelical congregations (a Church of Christ, a PCA congregation, and now an Evangelical Free Church since our move to a town where there is no PCA congregation), and none of them fit the picture painted in the headlines—you know, the fairly wild stuff that John Fea, in particular, has been covering on his blog for years—and wrote a book about it too.

The news headlines proclaim that conservative evangelicals are the voters who have been enthusiastically behind Trump from the beginning in early 2016 and are now continuing to stick with him through thick and thin. I am not disputing these findings, but I am also curious why I don’t know many of these evangelicals. My (heavily evangelical and Catholic) Twitter feed, instead, is filled with mourning and dismay from evangelicals I know over the other, Trump-supporting evangelicals. Yesterday, Marvin Olasky offered an explanation for one Iowa county that is quite striking, and you should read it, if you haven’t had the chance to do so yet. Part of the issue, Olasky reminds, has to do with people erroneously self-identifying as evangelical when they’re not exactly that. Olasky himself is, by the way, a Reformed (PCA) evangelical.

In the 2016 primaries, my very conservative evangelical semi-rural Georgia county enthusiastically supported its most famous ex-resident: Newt Gingrich. (On a side note, had he stayed in academia, Newt could have been my colleague in the History Department of the University of West Georgia. The mind boggles.) Then in the 2016 general election, I knew dozens and dozens of conservative evangelicals who wrote in Evan McMullin—in the hopes that the election would result in an Electoral College tie and would get thrown to Congress for a resolution. This scenario sounds like a deranged hope in retrospect, but indeed seemed a possibility to some at the time, this Vox article reminds.

To get back to my original point: Clearly there is more to the relationship of evangelical voters and Trump. What is going on here?

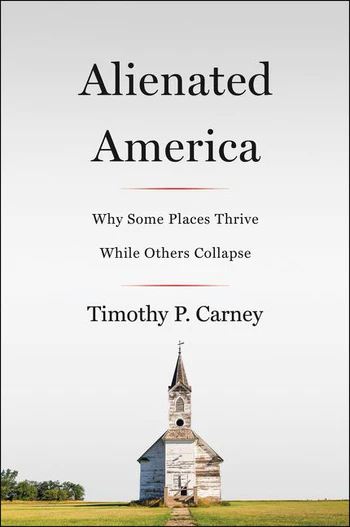

In Alienated America, published in 2019, Carney considers a striking phenomenon in the 2016 election: Trump voters tended to come from counties throughout the country where life was characterized by despair. It is to them that Trump could sell the message that the American Dream was dead, and it was time, therefore, to “Make America Great Again.”

Carney’s basic argument makes sense: the MAGA message is a hard sell to someone who is living in community with others, is part of many overlapping connected networks, and is actively focused on serving others. Trump’s message, rather, is one of utter despair, for those who felt active despair about life here today and/or who live in communities that are sinking deeper and deeper into hopelessness and isolation.

Drug overdoses, then, are a key part of this story, Carney argues: “If you were studying Pennsylvania and Ohio in the 2016 election, you could have predicted a county’s swing to Trump by looking at its rate of overdose deaths.” Even more striking, Carney notes the study of Washington Post reporter Jeff Guo, who found “a strong and dark correlation” right after the 2016 Iowa caucuses: “In some Iowa counties compared to others, middle-aged white people are twice as likely to die… These are the same counties where Trump was more likely to succeed.”

By contrast, if we look at the other extreme of the 2016 picture—conservative counties that were the least likely to support Trump in the primaries—Carney found people who are well connected to community structures and churches. Consider, for instance, “the Dutch factor”–very Dutch towns or neighborhoods, with their high rates of community involvement and church membership, were also the least enthusiastic about Trump.

Carney has a grim point to make overall: “The story of Election 2016, the story of the working-class struggle in America, the story of rising suicides and crumbling families, and the story of growing inequality and falling economic mobility, is properly understood as the story of the dissolution of civil society.”

Okay, this explains what happened eight years ago. The question I’ve been mulling over this week is: just how well has this explanation aged? I was glad to see that Carney has been thinking about this question himself, and his answer in the Washington Examiner this week is the essay with the descriptive title “Where does conservative Trump resistance survive (barely)? Where there’s more education and more church.” His analysis of the Iowa results this time around suggests that the argument still holds, to a degree, even as many previously reluctant Trump voters have decided that there were perhaps no better alternatives: “Places with a thick Christian culture resist Trumpism for a variety of reasons — mostly because in these places, daily community life is most rich and optimistic. Similarly, the most educated parts of Iowa were less supportive of Trump in the caucuses.”

I think the description “more education and more church” sums up well the communities I’ve lived in and churches where I’ve been a member my entire Christian life—college towns with a strong evangelical church culture, places where Christians remain focused on cultivating intentional relationships with each other and with the community.

There is a difference, it seems between “thick Christian culture” and a more generic church affiliation. But also, other categories are shifting, Carney suggests in concluding his article this week: “The definition of conservative is changing in the Trump era. So is the definition of evangelical. To understand the lay of conservative Christian America, we’re going to need to study harder.” The exact conclusion, in other words, that Olasky reached yesterday in his piece too.