Dreams of emancipation need not die

“The humanities aren’t dying, they’re being murdered.”

So goes the popular refrain from scholars of the humanities as departments close, tenure lines shrink, and research grants disappear. Scholars who otherwise wholeheartedly reject the great man theory of history quickly embrace it whenever the topic shifts to cuts in their own discipline. University presidents and provosts, so the argument goes, see the humanities as an obstacle to transforming once great universities into trade schools designed to meet the needs of big business rather than the body politic.

Yet, to put it delicately, most university administrators hardly arrive at work every day like Napoleon entering Jena. Most of them are following the crowd and making decisions based on trends and market data—which show that the number of students majoring in fields such as English or history has declined over 30% since 2009 and shows no signs of reversing. That the decline is happening across the entire industrialized world suggests that the root cause lies not in red state politics, the cost of college sports, or the collapse of high school humanities education, but rather in something far greater.

The work of the French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard might seem like an unusual place to search for an explanation. If postmodernism is ever brought to bear on this discussion it is usually by conservative writers who blame the postmodern turn for the humanities’ decline, treating it as a mistake that can be corrected by retracing our steps. Yet Lyotard’s landmark 1979 book The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge was mostly descriptive rather than prescriptive. And Lyotard laid most of the blame at the foot of a technology still in its infancy: the computer.

Even in the 1970s, Lyotard could tell that computers were changing the nature of knowledge. Digitalization was disconnecting knowledge from the knower. As a result, “the old principle that the acquisition of knowledge is indissociable from the training of minds, or even of individuals, is becoming obsolete.” In the future the relationship between knowledge and knower “will increasingly tend to assume the form already taken by the relationship of commodity producers and consumers to the commodities they produce and consume—that is, the form of value.”

Lyotard saw such a world of technological complexity as one in which “knowledge is and will be produced in order to be sold.” Knowledge, transformed into a commodity, would be invested in, owned, and guarded. In the modern economy, “knowledge ceases to be an end in itself” and becomes valued only for its economic utility.

It would be a future in which an abundance of easily available information would allow people to construct narratives confirming to almost any idea they wanted. Consensus about the truth would become impossible: everyone with their own story about what is true and no common ground upon which to demonstrate it. “Most people,” Lyotard concluded, “have lost their nostalgia for the lost narrative . . . what saves them from it is their knowledge that legitimation can only spring from their own linguistic practice and communicational interaction.” A better summary of the state of public discourse in our extremely online age is hard to find.

What becomes of the university in a world in which everyone has their own truth narrative? Here Lyotard is icily precise: The university once held the high calling of “the formation and dissemination of a general model of life” in hopes that an educated population would create a better world. But in a world without grand narratives, “universities and the institutions of higher learning are called upon to create skills, and no longer ideals—so many doctors, so many teachers in a given discipline, so many engineers, so many administrators, etc. The transmission of knowledge is no longer designed to train an elite capable of guiding the nation towards its emancipation, but to supply the system with players capable of acceptably fulfilling their roles at the pragmatic posts required by its institutions.”

Lyotard went so far as to predict that the instrumentalization of knowledge would eventually lead to the replacement of professors by computers which could deliver content directly to students. But even as Americans are unlikely to adopt fully online education—the residential college lifestyle remains an essential formative stage in American middle-class life in a way that it never has in Europe—the question remains: Is a lack of grand legitimizing narratives the underlying factor pulling students away from studying the humanities and towards pre-professional and marketable STEM majors?

Many popular defenses of the humanities—that they teach transferable skills, or that most graduates end up gainfully employed—preemptively concede that only instrumental knowledge can hold broader societal value. Yet many scholars are unable to articulate a more robust defense because doing so would require an appeal to grand narratives they themselves no longer believe. Without a shared system of values that gives social meaning to the study of the humanities, there is ultimately little reason for anyone to do so beyond personal enjoyment.

Lyotard was pessimistic about the prospects for turning back the clock: The ways in which technology had changed knowledge meant that such attempts would only create a system that would evolve to resemble that which it was meant to replace. And even if scholars rededicated themselves to the pursuit of truth, would enough people listen to reestablish a consensus around knowledge?

Lyotard’s famous solution was for every field to move away from making sweeping claims about the truth and focus instead on establishing truth within the confines of specific communities, periods, and disciplines. His own field of philosophy, he noted, had been “reduced to the study of systems of logic or the history of ideas” rather than making grand pronouncements on the meaning of life.

But even as he suggested this, Lyotard seems to have understood that this approach would ultimately be incapable of sustaining the academic humanities. After all, what benefit is it to know what a group of German philosophers thought about truth, or what people in early modern Britain thought about the nature of scientific knowledge, if none of it has a bearing on the ultimate questions of truth and knowledge? Does not all knowledge become trivial without a shared system of values to give it meaning?

For Lyotard, the ray of light at the end of the tunnel—or was it an oncoming train?—came from technology itself. Someday, he suggested, a computer of sufficient power could be developed that would be able to process all information. The computer’s code could then be made open to the public, thereby allowing the reestablishment of consensus around a shared narrative. The rapid growth of AI technology brings us closer to this future than ever before. Yet the outsourcing of knowledge to computers, which are fundamentally incapable of creating anything new, would represent a loss of our humanity. Perhaps the way forward for the humanities in the age of technology is to remind us what it means to be human—and to use the scalpel of history to reveal that which is truly permanent.

Christopher W. Jones is an assistant professor in the Department of History at Union University and an associate member of the Centre of Excellence in Ancient Near Eastern Empires at the University of Helsinki. He specializes in the history of Neo-Assyrian empire, and is currently working on a forthcoming book titled “The Structure of the Late Assyrian State, 722-612 B.C.”

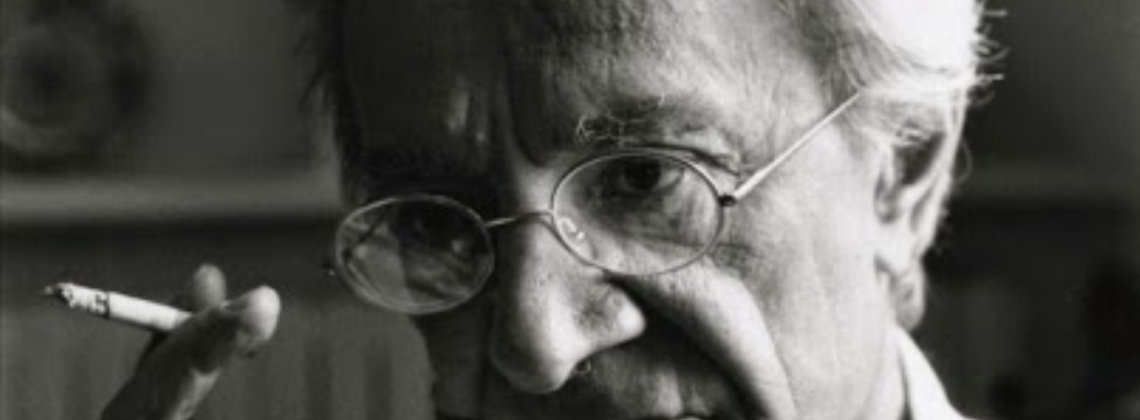

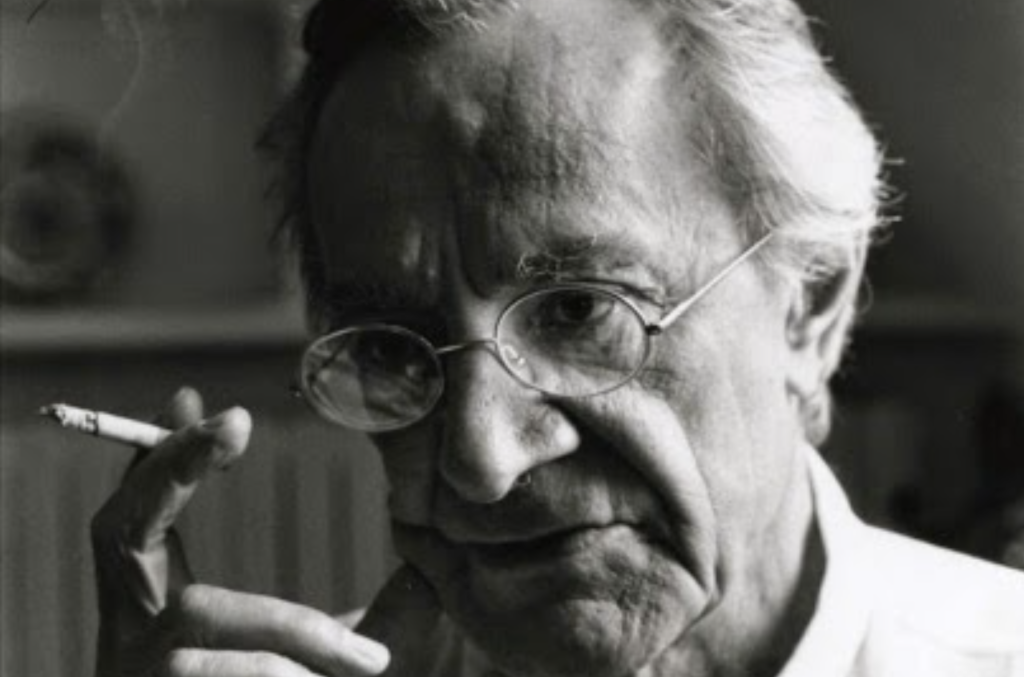

Image: Jean-François Lyotard