Mass literacy ≠ mass humanism

The shrinking of the Humanities on the American educational landscape is well-established fact. The number of students taking classes in subjects like English and history has been falling for a decade, as has the proportion of students majoring in such disciplines. Some smaller and regional schools are eliminating Humanities departments altogether; even the University of North Carolina system is eliminating distinguished professorships in all but STEM fields.

Some view these developments with alarm. I consider it reversion to the mean.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not happy about what I’m seeing. As a high school history teacher, I’ve watched as enrollments in my elective classes have dropped, and each year I nervously wait to see if I’ve got enough students for a class to run. In recent years I’ve been doing a lot of interdisciplinary and team teaching, which I enjoy and value on its merits. But when I craft my curricula, I’m mindful that a state requirement of four years of English creates a pool of students that is likely to make the difference between whether a class will fly or not, so I strive to make any course I develop eligible for English credit. My colleagues thought I was joking when I told them I made sure the first word of my newest elective is “money”—as in “Money, Morals and Mobility in a Modernizing Age.” My team of three—an English teacher, and Economics teacher (both deans), and I—will have our students read novels like Hernan Diaz’s Trust—the title is a pun on a financial instrument—and Mohsin Hamid’s How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia. The underlying principle of the syllabus is the well-established tactic known as bait-and-switch.

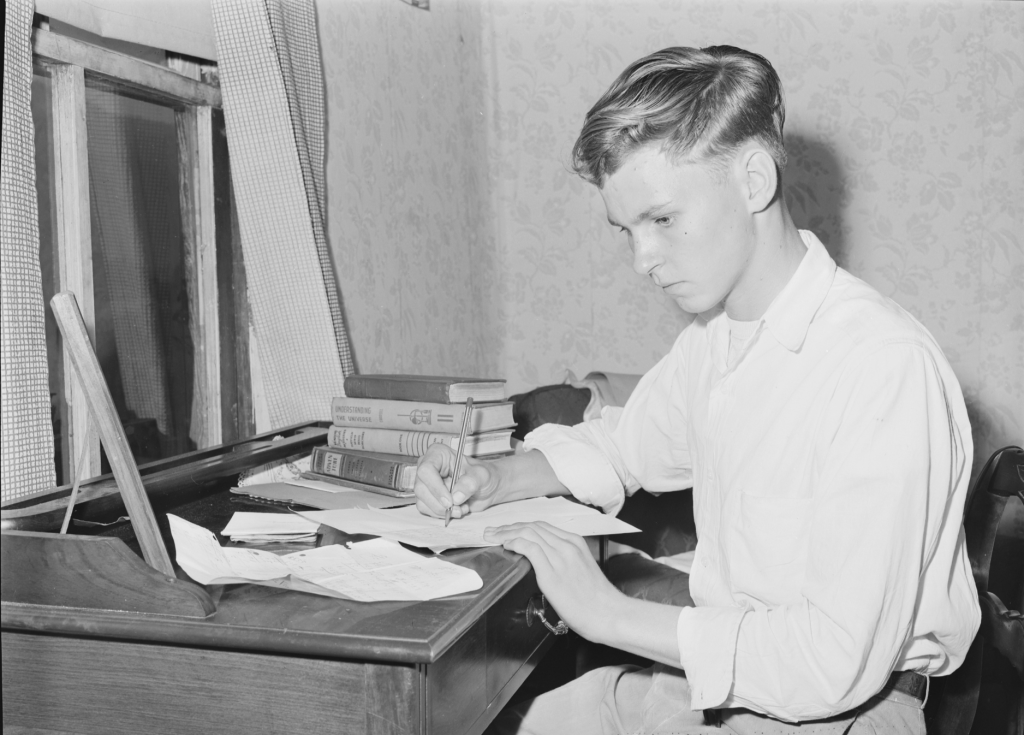

As a historian, I know the liberal arts—and associated concepts such as critical thinking and learning for its own sake—have always been minority avocations. Mass education has been one of the most important features of American society since the seventeenth century, when British colonists from New England in particular were probably the most literate people on the face of the earth. This development was foundational in the development of democracy, and the prerequisite for a meaningful free press. But mass literacy is not the same thing as mass humanism.

There was a brief moment when it seemed it might be so. Between 1946 and 1970 the number of Americans in college quadrupled: from two to eight million. It created an unprecedented mass of young people with opportunities for channeling their idealism into action through the life of the mind. In 1946, one out of eight people 18-24 years old were in college or graduate school; by 1960 that figure was one in four (in 1964 there were more undergraduates than there were farmers for the first time anywhere on earth) and by 1970 one in three.

Obviously not all these people were Humanities majors. But many of them were taking humanities courses, in large measure because they could afford to, literally and figuratively. (The profusion of cheaply produced paperback books helped make reading them a mass avocation, something today’s students, saturated in social media, generally now refuse to do.) This was the high-water mark of government-subsidized higher education, and the high tide of an American economy that lifted more boats than it ever had before, even if that number was inevitably finite.

But this was not the norm. The nation’s enviable state university system had been founded for vocational purposes—the A&M campus of the University of Texas denotes “agricultural and mechanical”—and while such schools swelled in the decades after World War II, they began to contract as American imperial affluence began to wane. That students today are mindful of their financial futures before, during, and after college aligns them with not only most Americans who have ever lived but with most young people in the world today.

The liberal arts are intrinsically elite pursuits. They require an element of leisure for their absorption and application, which is what small liberal arts colleges—and scholarships to attend them—should be about. One of the ironies of the contemporary academy is that many scholars have tried to democratize their fields, but have done so with any number of abstruse theoretical discourses that dispense with actually engaging with primary sources themselves. This approach functions as a vehicle for faculty careerism rather than educating the next generation.

Fortunately, there remain, as there always has been, those who attend to the work of sustaining a dynamic canon of shared learning. For the students who choose to engage it, there is actually a bona fide utility in doing so: Any given society needs—however small in measure—a group of people who creatively apply the wisdom of the past to the imperatives of the present. Upon them our future as a republic depends.

Jim Cullen, who teaches at the Greenwich Country Day School in Greenwich Connecticut, is the author of Martin Scorsese and the American Dream. His most recent book is Bridge & Tunnel Boys: Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel, and the Metropolitan Sound of the American Century.

Photo credit: Wikipedia Commons