The Claremont Institute doubles down on a dangerous argument

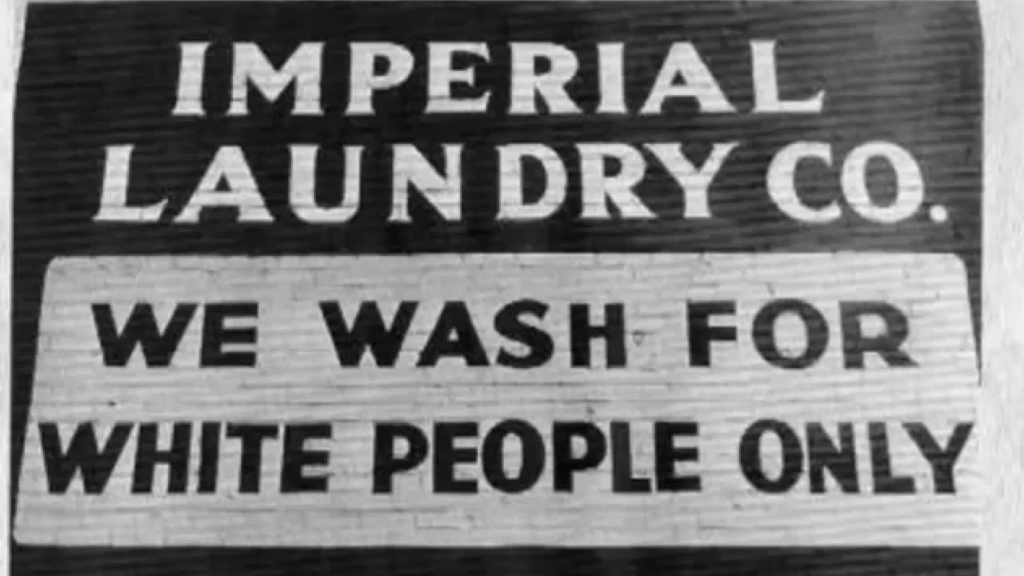

Two years ago, Current published my account of the Claremont Institute, a leading exponent of New Right ideas. The gist of my argument was that Claremont’s various authors and publications were contending, through a critique of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, for a right of private discrimination. A restaurant owner, for example, should be able to decide whom he or she will serve. Decisions of private individuals to group themselves by race or gender should be respected as an expression of a fundamental individual freedom, the freedom to associate. After all, a Claremont author argued, it is our tribal groupings along ethnic and religious lines that give meaning to our lives. According to Claremont, most of our current problems derive from the 1964 Civil Rights law because it outlawed most private discrimination.

Two years on, Claremont has doubled down on this argument. In doing so it has contradicted a key component of its political program: opposition to Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI). Worse, by more explicitly embracing white nationalism, Claremont is undermining the liberty it claims to be defending.

Claremont has continued to argue for a right to discriminate, pushing the cause of our contemporary troubles further back to the Brown v. Board of Education decision (1954). Brown is probably the most famous anti-discrimination decision ever made by the Supreme Court since it overturned for education the separate-but-equal doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). Plessy became the legal foundation for segregation. Rather than benefiting America by outlawing one kind of segregation, however, Brown was harmful, according to Jesse Merriam, one of the Institute’s Washington Fellows, precisely because it banned discrimination based on race.

In criticizing Brown, Claremont is not simply extending historically its search for the source of our current problems. After all, Brown was about discrimination in public schools. In criticizing Brown, is Claremont suggesting that discrimination by public institutions is acceptable? A Claremont Senior Fellow, Scott Yenor, has in fact argued that religious discrimination should have the force of law. He has argued that both “public and private institutions [should] honor Christianity above other religions” and that America should “legislate toward a Protestant vision of family life.” (Reassuringly, he tells us that he doesn’t want an established church.)

In the world Claremont wants, would discrimination by public institutions be on the basis of religion only? Would private and public discrimination on the basis of race be acceptable? Recent essays published by Claremont have praised a supposedly homogenous American culture that once existed and have claimed that our politics rest not on individual rights but on ties of “blood and faith” or “households and congregations.” For his part, Merriam limits himself to stating that we must be able to consider when private discrimination is constitutional and that if there will be “some discrimination and lack of diversity in some corners of American life, so be it.”

If not Merriam, then some more courageous soul following Claremont’s hints will certainly ask, Why is public legal discrimination on the basis of “blood and faith” wrong? Yenor has already argued for public discrimination based on faith. Why not discrimination based on “blood”?

There is only one reason such discrimination is wrong. It is wrong only if all human beings are created equal. On the basis of equality, the Declaration of Independence tells us, we join together and consent to participate in a common government because as equals no human has a right to rule other humans without their consent. Because our government derives from our equality, government-sanctioned discrimination—legally sanctioned inequality—is wrong, and it is wrong only for this reason. But Claremont and the new right have repudiated the Declaration and equality. This means that the Institute has now sided with the racist slaver John C. Calhoun rather than with the emancipator Abraham Lincoln.

As the reference to Calhoun reminds us, racialist thinking has long been part of American political thought. (Calhoun was an inspiration to Progressives.) This racialist thinking was beaten out of American conservatism—to the degree it was—by the unrelenting efforts of Harry V. Jaffa, in whose name the Claremont Institute was founded. Jaffa’s life’s work was to establish American politics on the rational ground of equality and individual rights. Abandoning the work of its founder, and abandoning the principles of the American founding, Claremont and the so-called New Right involve themselves in contradiction—and much worse.

Claremont claims to abhor “wokism” and “diversity, equity, and inclusion” (DEI) thinking. But it actually supports it. DEI thinking, claims Claremont, is anti-white racism and the greatest danger to America. Yet in advocating discrimination Claremont is advocating the principles of DEI, which separate Americans by race and seek to distribute life’s goods accordingly. If discrimination is good for Claremont, why isn’t it good for DEI advocates? Appeals to “blood and faith,” unlike the argument of the Declaration, leave no rational ground for distinguishing between one form of discrimination and another. DEI advocates have their blood and faith too. Once we abandon reason, all that is left is force or fraud. That explains why the essay that champions “blood and faith” also promotes an alliance “with the AR-15 crowd.”

Worse than its contradictory support for DEI is the dangerous direction in which Claremont’s racism points. Following Lincoln, Jaffa argued that any deviation from a full commitment to the principle of human equality led to tyranny. We are free because we are equal. As equals—to repeat—no one has a right to rule another without the other’s consent. In advocating discrimination, Claremont is turning away from equality. In turning away from equality, Claremont is preparing the way for tyranny.

David Tucker is a Senior Fellow at the Ashbrook Center. The views expressed here are his own.