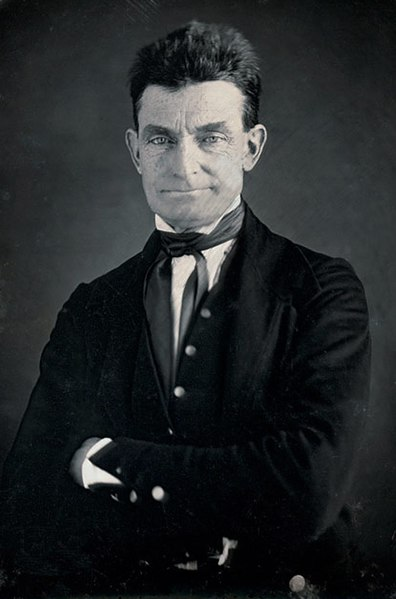

On December 2, 1859, John Brown was hung for the crime of committing treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Brown’s legacy is complicated, to say the least. Men of the time who whole-heartedly approved his hanging just as sincerely revered his memory.

Without him, there may have been no Civil War–at least, not when it did occur, and perhaps not with Abraham Lincoln as president. Brown had terrified the South, convincing them that the Republican party and Brown had the same aims, and that secession was the only way to assure their safety.

Secession brought the war, and it was only after many months of war that Lincoln became convinced that to destroy the rebellion, he must destroy its cause–slavery. Lincoln would eventually conclude that God in his providence had brought the war on America to do just that, His patience with the offense of slavery having finally run out.

Brown had attempted to spark a slave rebellion in October. He had failed. His insurrection was put down by troops led by Robert E. Lee, back in Virginia on leave from his duties in Texas.

J. E. B. Stuart was with Lee. It was Stuart who presented Brown with Lee’s demand for surrender, when Brown was holed up in the armory with hostages. Stuart recognized Brown from the days when he opposed him in Kansas. Brown politely refused: “No, I prefer to die here.”

As he sat on his coffin, being wheeled to his scaffold, Brown handed a soldier a note: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.”

Brown’s execution was a who’s-who of the future Confederacy. Thomas (not yet “Stonewall”) Jackson was there with his students from the Virginia Military Academy. Edmund Ruffin, the fire-eating secessionist who later was given the honor of firing the first shot at Fort Sumter was there. (Ruffin would also fire the last shot of the war, we might say, when, despondent over the South’s loss and unwilling to be ruled by what he called “the perfidious, malignant, & vile Yankee race,” he ended his life with a rifle in his mouth in June 1865.) A young actor named John Wilkes Booth also witnessed the hanging. Booth was a virulent white supremacist who nevertheless admired Brown immensely, calling him “a brave old man … that rugged old hero … a man inspired, the grandest character of the century!” Brown’s actions would inspire Booth to assassinate Lincoln.

For his part Lincoln was unimpressed: “John Brown’s effort was peculiar. It was not a slave insurrection. It was an attempt by white men to get up a revolt among slaves, in which the slaves refused to participate. That affair, in its philosophy, corresponds with the many attempts, related in history, at the assassination of kings and emperors. An enthusiast broods over the oppression of a people till he fancies himself commissioned by Heaven to liberate them.”

Frederick Douglass knew Brown well, had worked with him in fact, but declined to participate in his insurrection–Douglass was convinced it would fail, as it did. But he, like Booth, saw things to admire in Brown: “His zeal in the cause of freedom was infinitely superior to mine. Mine was a taper light, his was the burning sun. Mine was bounded by time, his stretched away to the silent shores of eternity. I could speak for the slave. John Brown could fight for the slave. I could live for the slave. John Brown could die for the slave.”

Henry David Thoreau went even further than Douglass: “Some eighteen hundred years ago Christ was crucified; this morning, perchance, Captain Brown was hung. These are the two ends of a chain which is not without its links.” Some months later another New Englander would write a poem expressing the same idea, and the poem would soon be set to a popular soldier’s tune called “John Brown’s Body.” Julia Ward Howe’s “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”–the purest distillation of Brown’s philosophy of sacred violence imaginable–is still sung in worship services today.

Historian Sean Wilentz takes a far darker view. Brown “was a violent charismatic anti-slavery terrorist and traitor.” The “American who most fully emulated John Brown in recent years was Timothy McVeigh,” he wrote in 2005. “In the era since the atrocities of September 11, 2001, one ought to be careful about finding some deeper good in terrorist politics of any kind.” Who knows “what Brown might have done if he had jet airplanes at his disposal.”

We are fated, says Wilentz, “to confront the legacy of John Brown whenever normal politics seems too blocked, too slow, too deafened to the cries of injustice. … The contrast posed by Brown is between a savage, heedless politics of purity and a politics of the possible. In flat political times, when the possible seems shrunken and democracy seems hollow, Brown materializes as a noble figure, an egalitarian paragon, a man ahead of his time.” But John Brown “was not a harbinger of idealism and justice, but a purveyor of curdled and finally destructive idealism. This is what Abraham Lincoln understood. John Brown deserves to live in American history not as a hero, but as a temptation — and as a warning about the damage wrought by righteous American terrorists, not just to their victims but also to their causes.”

Historian David Blight concludes, “I think he’s one of those avengers of history who do the work other people won’t, can’t, or shouldn’t.” But the mere fact that Brown acted, and that his actions sprung from noble ideals and had arguably salutary effects, does nothing to erase the moral dilemma at the heart of those actions. He forces us to confront “the meaning of martyrdom. … What constitutes the values or elements of martyrdom?” How “do we deal with revolutionary violence, in history or today? When can a cause be just … so just that violence in its name is somehow justified?”

Wherever we come down on Brown–monster? saint?–we are, if we’re thinking adequately, immediately confronted with the appeal of the opposite conclusion. He killed for “the highest ideals–human freedom and the idea of equality–but he also used the most ruthless deeds.”

“He killed for justice,” says Blight, summarizing the paradox. In that, he had something in common with Abraham Lincoln, but Robert E. Lee too.