In this story, medical extremity leads to an extremity of grace

Twin A: A Memoir by Amit Majmudar. Slant Books, 2023. 204 pp., $36.00

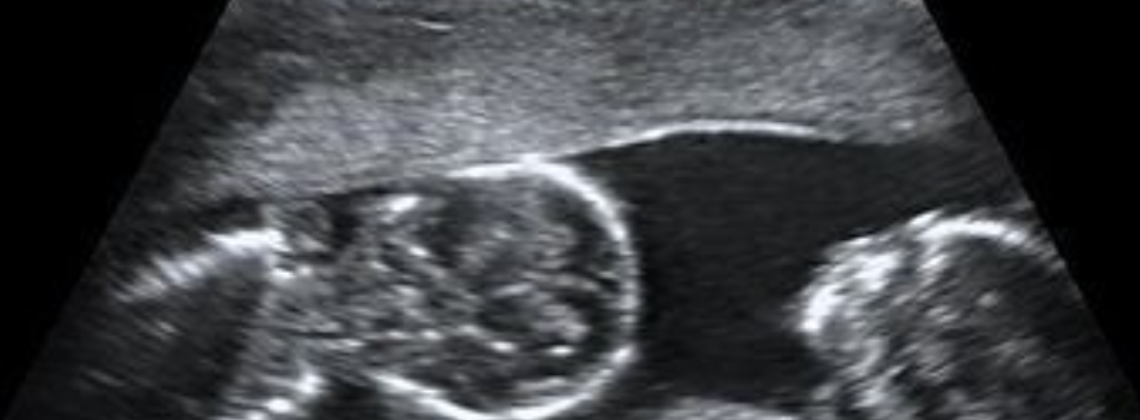

When Amit Majmudar and his wife Ami waited in an ultrasound room more than fifteen years ago, brimming with a combination of anticipation, wonder, and anxiety, they no doubt felt like any other parents awaiting that unforgettable glimpse of a firstborn child. Manifold surprises lay ahead, however. The screen revealed not one embryo but two. One of the twins appeared to be perfectly healthy. The other revealed a heart defect that would take further medical scrutiny even to be diagnosed. These moments would shape Majmudar’s identity as a father, would transform the life of his family, and would provide the impetus for his most recent book, Twin A: A Memoir.

Majmudar, a diagnostic radiologist and an award-winning novelist and poet, boasts an impressive CV. Both the doctor and the wordsmith have a voice in the memoir, as Majmudar alternates between poetry and prose. But, more than anything else, he writes as a father—a tired, worried, hopeful father who loves his family fiercely.

After skimming a summary of Twin A, a reader might wonder whether the particularity of Majmudar’s account has anything to offer. For those not among the forty thousand U.S. families who receive a congenital heart disease diagnosis each year, might not the steady literary rhythm of ultrasounds and catheterizations and blood draws and IVs prove somewhat . . . tedious? I am here to offer a resounding “No!” Twin A, which takes the form of an extended letter from Majmudar to his son Shiv, eloquently considers many of the experiences held universally by mothers and fathers—and indeed by all human beings.

Throughout the book, Majmudar reveals to the reader the poetry of the human body—the sheer miracle of our physical systems working together every moment to sustain life. He borrows language and themes from the epics of different civilizations, suggesting that if there is any epic greater to us than our own lives, it is found in the lives of our children.

Though I am not—at present—parent to a medically fragile child, my story shares similarities with Majmudar’s all the same. Majmudar and I both come from an Indian lineage (in his case on both sides of his family, in my case on one) with all of the support and expectations and preconceptions that this heritage entails. As he describes the continuous coming together of grandparents and aunts and uncles and cousins for each procedure that his son undergoes, I cannot help but think of my own extended family. No matter what differences or disagreements they might have, relatives always show up when the going gets tough. I cannot help but think that Western culture—particularly when it comes to illness and death—could learn much from Indian culture in this regard.

Furthermore, my family tree also boasts a pair of high-risk twins: my little brothers, born when I was two-and-a-half years old. The story of their infancy and birth is theirs and my parents’ to tell, but as I turned the pages of Twin A—especially now that I am a parent myself—I was filled with a renewed appreciation for the sacrifices that my parents must have made during those early years of my life. And I could not help but empathize with the figure lurking throughout Majmudar’s story: Twin B. He writes to his son:

Your brother has stayed in the background of this telling. He has been the one who played with you in the long waiting rooms, who helped you pick out your after-appointment stickers, who woke up with you at 5:30am on your cath mornings. His omnipresence in your story has tricked me into having him go without saying, like the air.

None of our stories belongs to us alone. Twin A’s story cannot be told without Twin B, without his father, without his mother, without the doctors and nurses and aides who assisted at each procedure.

In making this point and throughout the narrative, Twin A reminded me of two of my favorite books about ethics: Alasdair MacIntyre’s Dependent Rational Animals and O. Carter Snead’s What It Means to Be Human. Majmudar’s memoir is in no way a philosophical account; as he puts it (in terms that cannot fail but make any new parent chuckle and nod), “in those first four years, the only philosophical thought my mind experienced was bewilderment.” But he and his wife bear living witness to many of the philosophical observations made by thinkers like MacIntyre and Snead.

For MacIntyre, the paradigmatic example of parenthood is found in the lives of parents to children with disabilities. Although MacIntyre primarily considers children with impairments, both physical and cognitive, that necessitate a high level of parental care throughout life, I believe Majmudar also demonstrates an intensified example of the virtues that we all try to cultivate as we raise our families.

Concerned with the role of dependence in human virtue, MacIntyre identifies virtues of “uncalculated giving” and of “graceful receiving.” The former is readily apparent in the parent-child relationship, from the hospitality of the womb to the steady cycle of meals provided and clothing procured and pediatrician appointments scheduled. The latter, “graceful receiving,” is often more difficult to cultivate. Sometimes it begins simply with the grateful and humble acknowledgement of the role of myriad others in shaping our lives for the better. Majmudar does this time and again in the pages of Twin A.

“None of this happened in a vacuum for us,” he writes. “Your mother and I were never alone—not before, not during, not after.” He acknowledges, of course, the network of familial love and support standing behind him and his wife: the siblings and parents who cooked meals and held babies and provided relief. But he also expresses gratitude for their team of medical professionals and for the centuries of medical progress that made it possible for his son to have a fighting chance at life. Parents of healthy children, faced with many (true) stories of medical malpractice and overreach, sometimes forget to give credit where it is due. How many of us would not be here without the advances of the medical establishment?

Familial and local communities are not only the relational contexts in which parents learn to receive. We are graced by our children themselves, even when they seem to be only shapeshifting images on an ultrasound screen. Majmudar notes how his wife grew in her ability to be present to others going through difficult seasons. Undergoing the strain of raising a medically needy infant, she learned “how much even a brief text checking in can break the loneliness of suffering [and how a] phone call can give the obsessive mind a release valve.”

Even the mother of a healthy baby can learn this lesson—how many of us have been snapped out of circular worries about a child’s sleeping or feeding by the gentle voice of a woman who has been there before? His wife was always compassionate by nature, Majmudar tells his son, but “no small part [of this presence to others] is you at work through her. What you have taught her. What you have awakened.” It takes both gratitude and humility to acknowledge that we are perfected through the work of a tiny child.

Twin A also prompts his parents to deeper reflections on the meaning of human suffering. Although Majmudar’s writing is inspired by his Hindu beliefs, the problem of evil affects the faith of each of us. In addition to drawing from tenets of Hinduism, such as karma, Majmudar considers Christian approaches to suffering, most notably those present in the Biblical book of Job.

There is perhaps no harder task as a parent than watching one’s child suffer—whether, like Majmudar, you have to wait helplessly during surgeries and intense medical procedures or are merely up through the night cradling a toddler with a bad cold. In other words, it’s one thing to be at peace with God’s sovereignty over my suffering (suffering I have often brought upon myself!); it is a more difficult hurdle to clear when my son is in pain.

Much like Job, Majmudar does not arrive at any definitive answers here. But maybe answers are not what the suffering person needs most of all, he muses. “Explaining suffering and enduring suffering are two different things . . . Just because you can’t explain it doesn’t mean you can’t endure it.” If he can give his son only one of these, he is content for it to be endurance.

And the threat of future suffering is always lingering, even when everything seems to be going well. It’s part of the human condition, after all. “That sense of something lurking is how we go through life,” Majmudar writes. “[There] is never any point when we can sit back and say, ‘That’s it; that’s the whole story.’” This is true for all human persons. But it is perhaps especially true for parents.

In What it Means to Be Human, O. Carter Snead writes about the “unchosen obligations” involved in having children. The progressive embrace of a woman’s “right” to choose abortion rests on the faulty belief that no one ought to be forced into the obligations of parenthood before she is fully ready. But, of course, who is ever able to fully choose the responsibilities that come along with a new child? Even the parents of a healthy, “planned” infant cannot know what his or her future may hold—and yet still they commit to loving and cherishing this child, come what may. This radical commitment lies at the heart of parenthood.

At two points in the memoir the author tells of how the Majmudars made this commitment in a decisive way. The first is when they commit to Twin A, even with all of the uncertainty of his diagnosis. The genetic counselor advises Ami to undergo an amniocentesis, a procedure with well-documented risks to fetal outcomes, in order to gather more information about her son’s condition. Even though they are themselves members of the medical establishment, the Majmudars reject the procedure. They know why the doctors want more information at this point in the pregnancy.

“Is it ethical, or fair, or anything but atrocious to pick Twin B to live, and Twin A not to, just because Twin A doesn’t match nature’s default ‘Normal’ setting?” he asks. They already love their unborn twins—both of them. There is no further decision to be made.

Later, in the final chapters of the narrative, the Majmudar family grows from four members to five. Many parents, faced with years of expense and medical interventions and worry, would have decided that they were two-and-done. But instead, they give birth to their daughter. They were well aware that this pregnancy too was susceptible to risk.

Majmudar recounts a conversation with his wife from this time: “We are opening ourselves up, I warned her, because happiness is promised no one. We will be adding a third thing to fear the loss of: we will be creating someone out of nothing, and we will need that person to be happy for us to be happy.”

He expresses the tension felt in the heart of every parent, the strange joy of putting your happiness—partially—into the hands of a tiny little body. The Majmudars’ happiness must have seemed fragile indeed in the wake of that diagnosis so many years ago. In all their plans and dreams for the future, such a scenario never entered the realm of possibility.

And yet—“We are glad that life ignored our imaginations,” Majmudar tells his son. “[Otherwise,] we would not have dreamed big enough.”

Abigail Wilkinson Miller writes from northern New York state, where she lives with her husband and son. She recently completed an MTS in Moral Theology at the University of Notre Dame. Her writing can be found online at publications like Public Discourse and The European Conservative and at her Substack, Little House in the Adirondacks.