Right now my WWI research is focused on automobiles. One way I’ve been learning more about their use during the war has been by reading memoirs and accounts from drivers. These drivers tend to be pretty interesting. When the war broke out, the British actually used a couple dozen volunteers, who brought their own cars, to drive staff officers around the Western Front and occasionally ran messages and did some light reconnaissance. These men weren’t in the army and were kind of a civilian supplement to the war effort in its early years. And some of these men had real adventures.

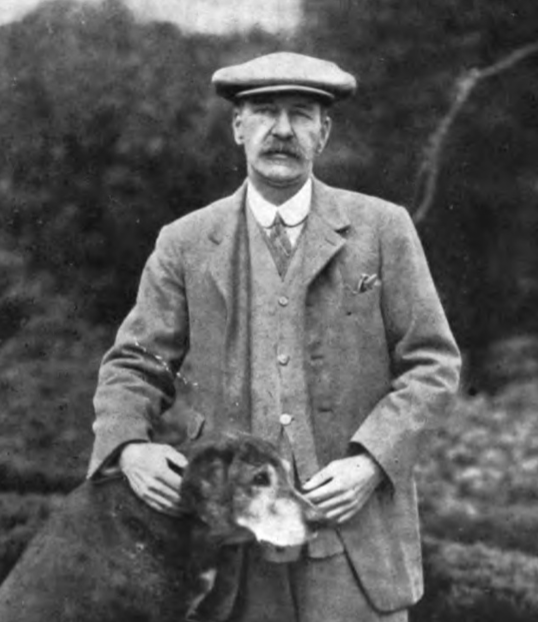

I first came across A. “Toby” Rawlinson through his book, Adventures on the Western Front, August, 1914-June, 1915, published in the 1920s. Rawlinson was a member of the Royal Automobile Club, so when the war broke out, he went over with around 24 other men and their cars, to help out. He was soon driving all over France and Belgium, where he was familiar with the roads because of his background in automobile racing.

Right away Adventures on the Western Front was gripping. Rawlinson had to navigate difficult terrain–slick roads, bad weather, crowded lanes. His car offered little protection from the elements. He took officers around, got shot at, etc. And it was in the early days of the war, before the trenches were set–there were advances and retreats. He had some narrow escapes.

Adventures on the Western Front is also entertaining because of who Rawlinson was and who he knew. After being shot at a few too many times, he went back to London and bought his own machine gun to affix to his car. He was happy with the results. As it happens, he knew a lot of important people. Sometimes on his journeys he would stop the night at a familiar chalet for a comfortable bed and a good meal. His brother was also General Henry Rawlinson, so he was briefly able to reconnect with him. Everywhere he went, Rawlinson met or made friends.

Whatever needed to be done, Rawlinson threw himself into doing. At one point, he got his brother to officially send him to Paris, where he went to review all the guns and mortars the French had ever devised (and kept at a facility in Versailles). His mission: to see if an old mortar could be adapted and improved to counter the German minenwerfer. He found one and made the improvements. (They were called Toby mortars.) And he got involved in devising better fuses and shells, too.

It was all going pretty well until he got sick and had to go back to England for a spell. While there, he got a letter suggesting that he really shouldn’t be using a military title in Europe which he didn’t have (he had been temporarily called an officer by superior military personnel at times to get past some sentries). Offended, Rawlinson withdrew his services from the Western Front. But in no time at all, he had joined up with the Admiralty, put in charge of a mobile defense unit of armored cars. That led me to his next book, The Defence of London: 1915-1918.

The Defence of London contains Rawlinson’s adventures with armored cars and fixed guns and the attempts to stop zeppelins and aeroplanes from attacking England. At this point Rawlinson was in the Navy, but initially operating very independently. He worked to acquire guns from France, devise new fuses, establish fixed and mobile positions for defense, etc. He was able to use his creativity and work with an elite team. He eventually found himself fully embedded in a military chain of command and not always near the top. He encountered what he called “red tapeism.” But he put in three years before he resigned.

Of course, Rawlinson’s story doesn’t end there. When he resigned from the Navy, he offered his services up to the Army. The next book is Adventures in the Near East: 1918-1922. I’ve already put in my Inter-Library Loan request. How can I not want to know more? Someone like Toby Rawlinson is worth reading about.

The great man theory of history isn’t very good, but there have been some great men and women in history. There are some people who are just more interesting or inspiring than others. There are some people who have led exceptionally adventurous lives. Sometimes we can learn from them. Rawlinson was a bold experimenter, someone who asked forgiveness rather than permission, and someone who was always willing to volunteer himself. The world might be a better place if a few more of us were more like Rawlinson.

There are all kinds of really interesting people in history who aren’t nearly as famous as you might expect. Jimmy Winkfield was a black jockey–the last to win the Kentucky Derby–who also spent a significant amount of time in Russia and France. Did you know that Merian C. Cooper, who produced King Kong, also made an ethnographic film called Grass, about a tribe in Persia herding their animals to seasonal pastures? You can watch it here. You might be familiar with Out of Africa, but do you know about Beryl Markham, who was an early twentieth-century female aviator in Kenya? None of these people are so obscure that someone hasn’t written a biography about them, but I bet plenty of people haven’t heard of them.

Why read the story of someone like Rawlinson? Why watch Grass? Because it’s good to have a few examples of people who led truly adventurous lives and thought outside the box. So much of what we see is filtered by algorithms and influenced by what is thought to be popular. Even many of our current cultural heroes are varying types of vanilla. But when we see that other people can do incredible and unlikely things, it reminds us that so can we. When we see that others can succeed off the beaten path, it reminds us that we have more options than we seem to have. People with wide-ranging interests and experiences help remind us that it really is a wide world out there.