What does it mean to live well in old age?

Americans are bad at aging. (Note: Not being good at it doesn’t prevent us from having to do it.) Part of the problem is that we idolize youth. This idolatry is particularly conspicuous in the influential demographic that now struggles noticeably with aging, though maybe we need not trace every problem to that generation. Okay, boomer?

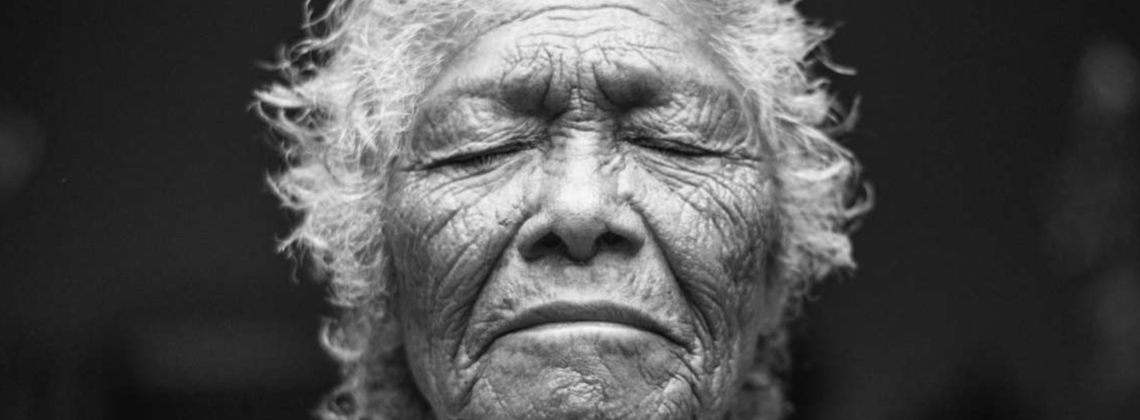

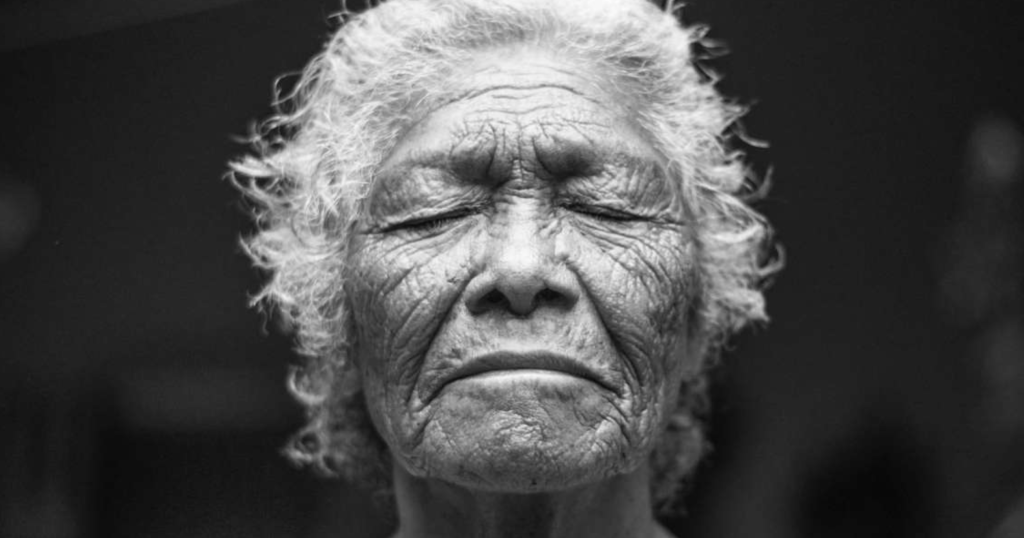

Youth rules. Arbiters of taste cater to young people through popular culture, music, advertising, film, fashion. Beauty standards stay young, favoring the smooth, the firm, the glazed-donut cheek and the flexed muscle. In obedience to that ideal, people who are not young pay their dues by pretending they are. They clear away spot, blemish, and wrinkle by chemical or scalpel, banishing parentheses around mouths or bird feet at eyes or parallel tracks between brows. Older people try to stay young by playing sports, trying on-trend hobbies, keeping up with cool kids. Nothing is wrong with sports or hobbies or fun companions, but they won’t stall time.

There are some good reasons to dread getting old. Aches and pains, creaky joints, reduced mobility, dimmed sight, and muffled hearing often come with advanced years. For some, what may be worse is the inkling that one’s best life is in the rear-view mirror, with mostly grief and loss up the (short?) road. To fight that discouragement, the 1990s popularized new ideals of successful aging, replete with sound body, fresh goals, and social connection. Most people say that as they grow old they want to remain physically healthy, mentally engaged, and integrated in satisfying relationships. Still, most will approach their final years in physical decline and isolation. Problems—structural and personal—keep us from aging as successfully as we wish.

Decline comes to all. But getting old can be especially hard on women. Women get a small window, maybe a decade, to go from “babe” to “hag,” Jessica Grose writes, an insight that troubles, starting with the fact that “babe” persists as the word we use to describe women’s peak. In the 1980s, when I was in high school, nice people were learning not to call women “girls” any more, and by the time I was in grad school, manners mandated that fourteen-year-olds starting high school be called women too. Maybe it’s because they missed out on years of girlhood that Gen Z and millennial women online have taken to calling themselves “girls” in cheeky phrases: girl boss, girl dinner, hot girl walk, and so on. For grown women the tip backward to girlhood might be cringe-worthy but is not hard to understand if the choice is between babe and hag. Hag, after all, is no harmless label. Older women at a few historical periods have not only been denigrated but also persecuted, likelier than other demographics to be accused as witches and punished accordingly.

But like that flap beneath my upper arm that keeps on waving after I stop, the pendulum swings.

Older women have gotten boosts in the last few years. During COVID, women accustomed to keeping up youthful appearances had to forego Botox or plastic surgery or dyeing their greys at salons. Some women have never gone back, learning to love age-appropriate faces and silver hair. Recent books encourage overstressed working moms, declaring that life actually will be better after middle age when they have come into their own and family demands have ebbed.

Even Barbie got on board last summer, giving seniors a boost. In Greta Gerwig’s movie, the doll-come-to-life sets her gaze on an old woman sitting on a park bench. The viewer might wince a moment, wondering whether Barbie will be repelled or (more likely and absurdly) tell the woman she is cute, which is what some young people I know say about their grandparents. Barbie skips the trap. She tells the woman she is beautiful. The older woman, played by Gerwig’s friend, costume designer Ann Roth, tells Barbie that she already knows she is beautiful. That response is supposed to make the audience cheer. Or nod, or cry, or something.

I doubt that Barbie’s gaze is enough to make older-woman beauty standards triumph in the mainstream. But these shifts at least open possibility to imagine what aging would be like in America, especially for women, if we could remake the experience according to a model proven to work.

Who does best at aging in America?

Nuns. Nuns live longer and maintain physical and psychological health better than those outside convent walls. Paradoxically, these women score higher on American indices of successful aging by doing the exact opposite of what popular advice requires. In Embracing Age: How Catholic Nuns Became Models of Aging Well, anthropologist Anna Corwin studies the Illinois motherhouse of the Sisters of the Sacred Heart to understand why. The answer is all paradox. Sisters age successfully by rejecting tenets of successful aging. Instead of trying to extend the body’s peak performance as long as possible, the sisters do not waste energy fretting over inevitabilities. Early commitment to common life is what keeps them from isolation in later years. Schooled by vows that being matters more than doing, they value each other though infirmity prevents some from contributing to the common work. Even sisters who may seem unable to do much of importance, as measured in the outside world, keep plenty busy and avoid the sting of feeling useless. When Corwin interviews one sister about how she spends her days, Sister Doreen reports that she “visits the elderly.” Doreen is in her late nineties.

Another sister goes room to room daily to talk to sisters who are immobile or in pain, and she massages their feet while she sits with them. I can hardly think of a better model of dignified human community. Well-meaning folk might tend to infantilize older people, perhaps as check against their own anxiety. Maybe it is an accomplishment to find one’s grandmother cute rather than haglike, but it hardly upholds dignity. Instead, these sisters keep their dignity and respect others’. They avoid demeaning “elderspeak,” they joke with each other, they know how to serve and be served.

The beautiful woman on Barbie’s park bench, or you, or I, might not be able to do as the nuns do. Their ways are not easy to replicate outside convent walls. These days, even people committed to each other by blood or vow seldom pass whole lives together as housemates or neighbors. Scant is our repertoire of loving service. Scant is our vocabulary for work that does not earn money. Unlike the sisters, more of us probably spent youthful years pursuing what we wanted rather than giving up all for a pearl of great price. Thus most of us, men or women, might not be able to wind down lives so kindly and fruitfully as these Sisters of the Sacred Heart. Still, any plausible alternative model of aging could be fruitful in the contrast it provides to the prevailing one. Those hoping to live well in old age could start with little acts of imitation inspired by monastic emphases: Embrace each other and all persons, speak carefully, let go, accept limits.

Agnes R. Howard teaches in Christ College, the honors college at Valparaiso University, and is author of Showing: What Pregnancy Tells Us about Being Human. She is a Contributing Editor for Current.

Image credit: Cristian Newman, licensed under CC BY.