The son of a Louisiana statesman looks back at the world of Huey P. Long

I remember when I first read All the King’s Men. Travelling south on Louisiana I-10 with my dad, I noted how the book resembled the world outside our window: “You look up the highway and it is straight for miles, coming at you, with the black line down the center coming at and at you, black and slick and tarry-shining against the white of the slab, and the heat dazzles up from the white slab so that only the black line is clear, coming at you. . . .” The thrum of the highway harmonized with Robert Penn Warren’s description, and I thought it was uncanny—like grabbing a door handle at the same time as someone on the other side. It was only the first similarity between our Louisiana backdrop and a book that remains one of the best novels, certainly the best political novel, I’ve ever read.

I was struck too by the way the characters spoke. “It was still hotter than hell’s hinges,” says Jack Burden, the novel’s narrator. Even better: “Like a stuck phonograph record or a chicken-hungry preacher getting over the doxology. The words came but her mind wasn’t on them.” This verbal ingenuity, born from a rural setting, resembled expressions from home. I knew people who would have smiled, nodded, and tried to do Warren’s character one better. Happier than a dead pig in sunshine; drunk as a chicken; happier than a town hog in slop: Sayings like these punctuated conversations I grew up hearing. The dialogue from All the King’s Men was so recognizable it felt more recorded than invented.

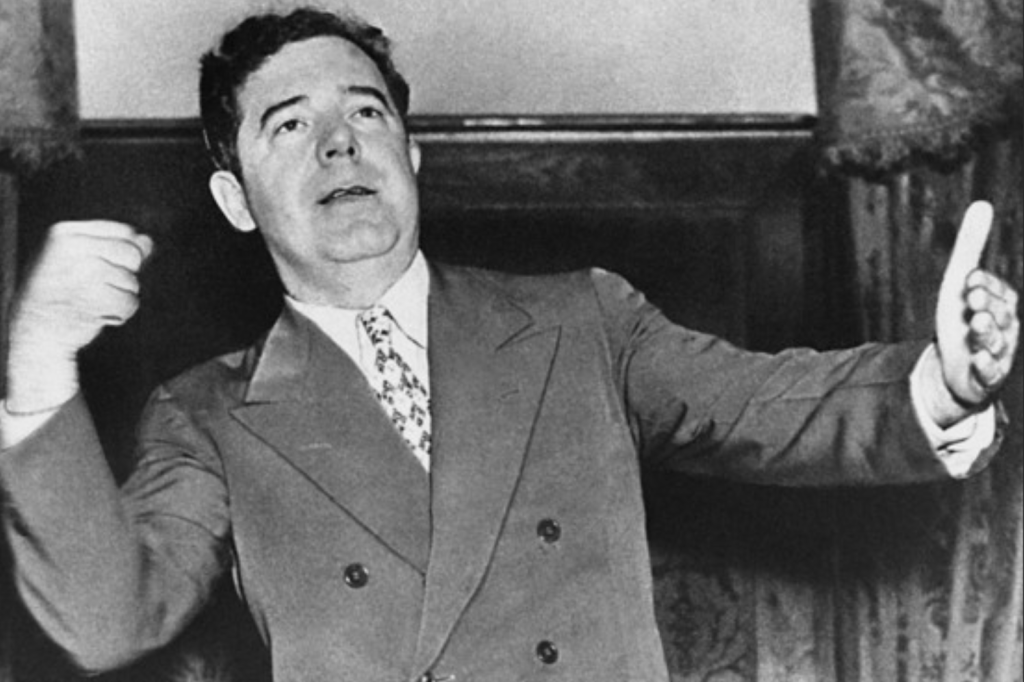

Although Warren differentiated the novel’s “politician hero” Willie Stark from Louisiana governor and US Senator Huey P. Long (“Long was but one of the figures that stood in the shadows of imagination behind Willie Stark,” Warren would say), the resemblance is certain. I read All the King’s Men in the wake of Long’s history and saw the novel as a reckoning with his life and influence, which were still realities when I grew up. My first exposure to Long came in a Louisiana history class in junior high. My first sense of Long as a real person was seeing the state capitol he built—and the pockmarks in its walls where he was shot. I attended the state university Long patronized, knew a member of his extended family in college, and watched state officials base their careers on his.

Understanding Long’s history was part of our family lore, too: My dad took a class with T. Harry Williams at Louisiana State University the year Williams won the Pulitzer Prize for his biography Huey Long. Dad remembers when someone asked Williams what he thought, really thought, about the former governor. In response, Williams confessed a biographer’s compassion: Having spent so much time considering Long’s life and work, he admitted that he was endeared to Long. In his biography he put it like this: Men of power “may do great good or evil or both, but whatever the case they leave a different kind of world behind them. Their accomplishment should be recognized. I believe that Huey Long was this kind of man.” Williams also said Long subscribed to Willie Stark’s political approach based on what he understood to be the thesis of All the King’s Men: “. . . the politician who wishes to do good may have to do some evil to achieve his goal.”

My own proximity to Louisiana politics made All the King’s Men especially evocative. My father was elected to the state legislature when I was in high school. On the day before he was sworn in he took us for a walk around the capitol grounds, where we saw the Huey Long statue. According to tradition, the statue was illuminated or not depending on the sitting governor’s appreciation for the former statesman. When Dad was elected in 1994, the statue was lighted. Long’s influence was more or less acknowledged but certainly always present, and there were people who had seen his career firsthand and remembered it well. When Dad first began his work in the senate, Senator B. B. “Sixty” Rayburn told him, “Son, I’ve been in the legislature longer than you’ve been alive.”

Before Dad’s first legislative session, my traveling and campaigning with him offered a lesson in civics and Louisiana culture—not to mention human nature—all of which made Warren’s novel all the more striking. In his famous analysis of American society, Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville notes the American tendency to “constantly form associations.” As he puts it:

They have not only commercial and manufacturing companies, in which all take part, but associations of a thousand other kinds, religious, moral, serious, futile, general or restricted, enormous or diminutive. The Americans make associations to give entertainments, to found seminaries, to build inns, to construct churches, to diffuse books, to send missionaries to the antipodes; in this manner they found hospitals, prisons, and schools.

When my dad ran for office, the American spirit of association was alive and well. Political campaigning meant addressing Rotary Clubs, veterans’ groups, farmers’ associations, business groups, and alumni organizations. The stump speeches in All the King’s Men conjure a backdrop of Louisiana’s District 33—then part of eight parishes in the north of the state—and all the miscellaneous groups across the region, requisite audiences for a political campaign.

Willie Stark’s ability to captivate recalls the remarkable charisma of the politicians I saw in action, almost all of whom were raconteurs. From festivals to formal debates, legislative chambers to church parking lots, I witnessed some of the best oratory, the kind that holds attention out of necessity. When Warren describes Stark’s capacity to spellbind, I know what he means. A friend who moved to Louisiana for college told me that when he first saw Governor Edwin Edwards speak—with his intelligence, wit, and charm—he thought, That’s probably what the devil looks like.

Returning to All the King’s Men decades after I first read it, I still find the book striking for its insights, especially its depiction of demagoguery and populist politics. Immediately we see the power of Willie Stark’s appeal. When Stark stands before a giant picture with his image, Warren helps us recognize potent mythmaking, “Under the picture was the legend: My study is the heart of the people. In quotation marks, and signed, Willie Stark. I had seen that picture in a thousand places, pool halls to palaces.” The remark suggests the extent of Stark’s appeal, his strategic understanding of human nature, his ability to beguile.

But the novel’s point of view is most remarkable. Jack Burden, a journalist turned aide to Governor Stark, sees firsthand how politics works, how deals are made—the temptations of power and money, the ensuing collateral damage. Jack, a student of history, is burdened by knowledge, and we see him shoulder even more in the story, with his ringside seat to corruption, degradation, and betrayal—others and his own. All the King’s Men shows us Jack’s cynical malaise up close.

The most surprising thing about Jack’s experience, however, is that after the story’s tragic events he rejects his earlier perspective. He even plans to return to politics with an outlook akin to what philosopher Paul Ricoeur calls “second naiveté,” a disposition informed by doubt yet not bound by it. Having seen the terrible failings of human nature, including his own, Jack nevertheless moves beyond disillusionment to acceptance and—as suggested by the book’s ending—responsibility.

I will never forget the novel’s last line, one of the most memorable of any novel I know: “. . . soon now we shall go out of the house and go into the convulsion of the world, out of history into history and the awful responsibility of Time.” Poet that he is, with an awareness of the line’s connotative weight, Warren uses “awful” to invoke dread but with elements of wonder and mystery as well. Even with all the dreadful things Jack has witnessed, there is humility in his recognition that the world yet has meaning. In its own sober way, the ending manages to disqualify cynicism and even invoke something like its opposite. Which is to say: hope. Despite the novel’s grim metaphysics, Jack’s outlook is echoed in some of Warren’s most moving work. His poem “After the Dinner Party” invokes the darkness of mortality only to close with the following line: “Even so, one hand gropes out for another, again.”

Thus the ending of All the King’s Men is a kind of beginning for Jack—and for the reader too. As someone who puzzles over life’s relationship with art, I find this aspect of the novel most moving. The best fiction returns us to our own lives with new perspective and understanding. All the King’s Men invites us into the burden of time—but with the recognition that our choices matter and that hope is possible. Today, over seventy-five years since the novel was first published, in our era of ideological stringency, when technology accelerates our worst aspects and we’re encouraged to fear our neighbors, cynicism and disaffection seem more justified than ever. The novel’s final point is relevant still.

When I ask my father about how state politics has changed since his time in office, he offers a lament: “When I went to the senate, I could not have told you with certainty who was a Democrat or a Republican. There was not a lot of concern about party labels. It was about support of good ideas and people. The partisanship was not there.” He says that despite political differences, there was always collegiality, friendship even, among his legislative cohort. They had cafeteria meals together, worked in adjoining offices, spent immeasurable hours in proximity. He says, “When you walked off the floor, the fight was over.” Accessibility has changed too: He says the ability to legislate was based on personal communication, and people were less isolated. They weren’t raconteurs for nothing.

One final note: Novels are stirring for the way they enter our imaginations and help us see what we otherwise would not. All The King’s Men is, among other things, about Jack Burden’s reckoning with who his father is. Reading it again, I recognize my own firsthand witness to an extraordinary statesman: a farmer from a two-hundred-person town who won a senate seat with a door-to-door campaign, who loved the work, not the limelight, and who served the state with wisdom, integrity, and generosity. Even as I hope for better days ahead, I know Louisiana will never see another like him.

Robert Erle Barham is Associate Professor of English at Covenant College in Lookout Mountain, GA. He is the deputy editor of Current.