Last week I wrote about the universalism behind the French Revolution and its tremendous appeal. But the French Revolution was a long time ago. One aspect of the present seems to be a reluctance toward universalism. If this is indeed a postmodern era, it tracks with Jean-François Lyotard’s definition of postmodernism as “incredulity toward metanarratives.” This can be very frustrating when trying to decide a course of action or interpret the world around you. It can muddy the waters in very serious ways. Principles can often lose out to particulars.

Without any nostalgia for the French Revolution, we can see the obvious appeal of universalism, or at least an overriding belief in an ideology or a conviction about the best way to uphold a principle, regardless of circumstance. It can be incredibly clarifying. It can help determine a course of action without fifty years of consideration. The same is true of a decided allegiance, one knows who the allies are without much work. And yet, such seeming clarity can actually obscure too much.

In the middle of the twentieth century, many people in Western Europe and the United States believed that communism was not only the best system but that it would be a better future for us all. Among some public intellectuals, support for communism included support for the Soviet Union. It seemed clear that communists should support communist countries. After all, that was consistent with the universalism of communism. In most cases, these people had little knowledge, and sometimes no experience, of what the Soviet Union was really like. Of course, when the West gained more awareness of what the Soviet Union was like, it wasn’t only the Soviet Union that was discredited in the West, it was the entire concept of communism for most people. And people who thought they were standing on principle had actually become public apologists for Stalin.

Whenever we have an automatic allegiance to a certain kind of label, we are in dangerous waters. What do we truly know about the situation on the ground? Today some conservatives are vocal in their support for Hungary and Russia, or Uganda, as “conservative” and “Christian” countries. Their loyalty to proclaimed conservatism is strong. But few of those fans actually live, or would like to live, in those places. And what will happen when the particulars of how those countries operate become more widely known? If the linking between these countries and a universal idea of conservatism is successful in the public mind, what will that do to the image of conservatism, as a whole? Who and what will these pundits have been apologists for? The same applies for every situation in which people at a great distance are certain who the good guys are, without needing any information to verify that.

This risk always applies to ideology. It may never be the safe harbor for moral clarity that it seems to be. Vaclav Havel suggested that ideology distances us from the truth, because it creates an intermediary between what we believe and the reality that exists. It distorts reality. When we buy ideology, we sell facts. In “Power of the Powerless,” Havel argues that ideology separates us from our moral responsibility. Ideology outsources our moral compass to a system, a way of thinking. Ideology can give us marching orders, but do we want to walk down the path it suggests?

Even loyalty, in general, includes risk. Loyalty is meaningless if it is entirely conditional but it may be morally abhorrent if it is never reconsidered. One can think of the hot water Ashton Kutcher was in earlier this year, when he compromised his public stand against human trafficking and child sexual abuse with his letter of support for his friend, convicted rapist Danny Masterson. It is easy to be critical of Kutcher, but how many of us have unquestioned personal allegiances, to people or causes or positions?

Without universals, certain operations become quite complicated. You can ask all the metric system countries how much they enjoy dealing with the United States. Without allies and enemies, foreign policy is beyond complicated, maybe impossible. Sometimes action is required before we have time to fully process the moral ambiguity in a situation. We cannot always live in the particulars.

But when we are acting as individuals, at least, we are best off without automatic replies in many situations. One needn’t be entirely relativist or cynical to keep one’s list of unquestioned allegiances short. Very often we’re for or against a side based on our teams or principles, but we have no idea what is actually going on and lack the proximity to know about the relationship between “our” side and “our” principles. A reluctance to immediately “know” what to think about a topic can be a sign of appropriate humility. Even when we have firsthand encounters with different people and situations, we are still operating within the limits of our human frailty.

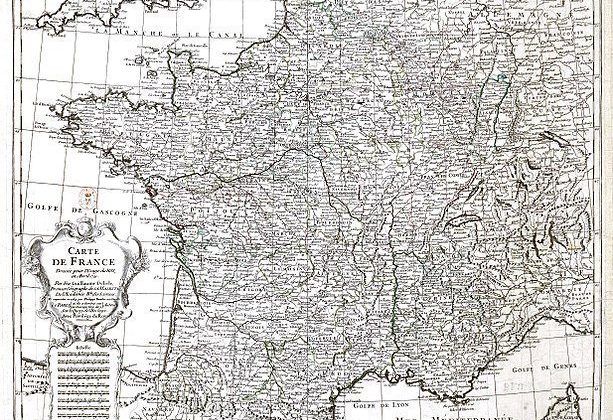

The French republican calendar has inspired some great Twitter (X) accounts, but 1792 was not a new dawn of human history. The French Revolution was a very significant moment in human history—for the whole world—but its hopes were not universally realized. If we could call up those early revolutionaries, they may still insist on the universal relevance of their principles, but they would have to recognize that their principles were not universally achieved and they did not manage to make their revolution a revolution for all people. In the same way, we may hold unwavering principles, but we can remember that we may not always have an immediately clear vision of how they apply in all contexts. There are times when our desire for moral clarity can lead to us being complicit, or worse, in events far from our ken.