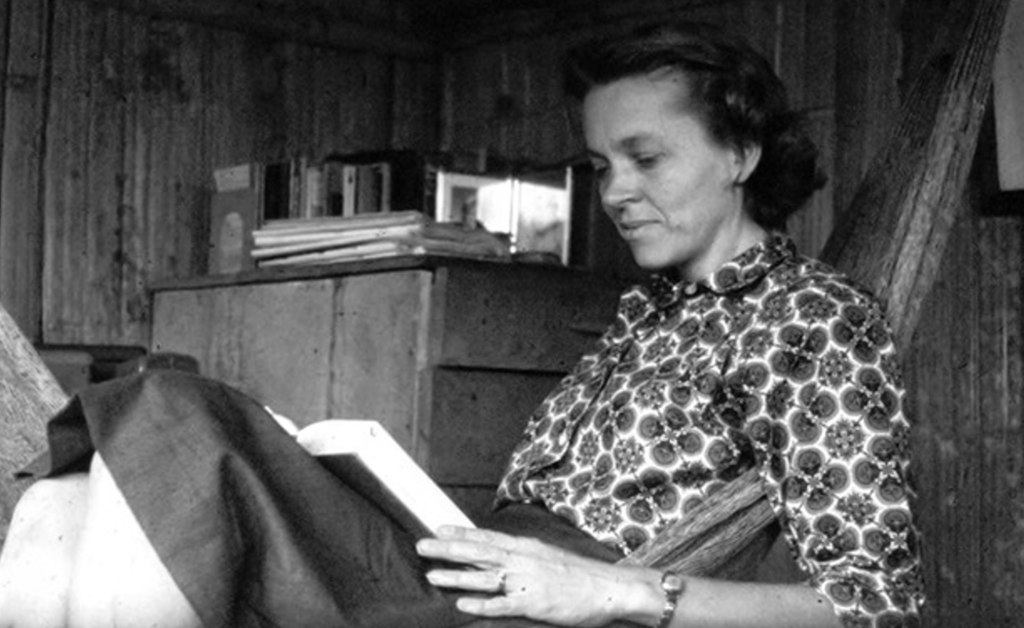

Elisabeth Elliot was not just a subject to write about. She was a writer to emulate.

For half my adult life I’ve been researching and writing about the writer, speaker, and missionary Elisabeth Elliot. I began the project in the summer of 2012, and this summer, 2023, the completed book went out into the world. I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about the events of Elliot’s life, the facets of her personality, the cultures that helped form her. I’ve read her letters, extensive excerpts from her journals, her newsletters, her books, and many of her speeches. I’ve spoken with more than two dozen of her family members, friends, and acquaintances.

I’ve also spent a lot of time thinking about the what, why, and how of biographical writing. I’ve read biographies and paid attention to how the authors handle the nuts and bolts of their craft. I’ve read biographers talking about the art of biography and thought about how to understand the fragile, soap-bubble beauty of what we call the self. I’m still working my way through the Oxford History of Life-Writing as each volume comes out, learning about varied expectations for what biography ought to do and how those expectations keep changing.

Aspects of Elliot’s own work have neatly overlapped the two tracks of subject’s life and biographer’s art. Elliot was a voracious reader of biographies, and she wrote several herself. Many of the biographies she read and wrote were of missionaries. Thus she and I share not only the semi-universal preoccupations of the biographer but also some questions that are perhaps distinct to writing about evangelicals.

Sources are a foundational concern of the biographer, both practically and philosophically. As Hermione Lee says, “You can only access [the subject] in as far as you have materials and witnesses to allow you to access them. You are at the mercy of what you can find and read and hear and see.” At present there is a general understanding that in biography you mustn’t rearrange events to support the themes of the work, or invent things that ought to have happened, or delete scenes that don’t advance the plot, and then present your work as the true story of a life.

This raises practical questions. There’s the question of whether enough information exists to tell a story. Perhaps materials have been lost or destroyed, or witnesses have aged and died. If they exist, some materials may be available for study in libraries and archives; some may be in private collections, and the owners must decide whether to trust you with the information they contain. Witnesses too, if they are living, must decide whether they will trust you with their stories. As biographer Carl Rollyson notes, these challenges have led to more than one noteworthy biography that revolves around the search for sources as much as around the life of the subject.

If the biographer gains access to source material, new questions arise. You can have, in a sense, too many sources—a lack of material in one part of a life, and still more than you can manage in another. Robert Caro has described his sinking feeling when he first entered Lyndon Johnson’s presidential library and realized that the archives contained more papers than he could ever read. The biographer must determine how to triage materials, how to make an educated guess about where key information is likely to be.

The biographer also must evaluate how much weight to give material from various sources, particularly when sources contradict each other. People omit information that doesn’t seem important to them, or that they don’t think should become public. They forget things; they make mistakes; sometimes they invent things—perhaps out of self-protection or self-aggrandizement or mischief or malice or meaning well. All these things can be true of witnesses speaking directly to the biographer, but they can also be true of sources written long before the biographer was on the scene.

Writing about a widely known evangelical Christian can hold added complexity. There is a tendency in the evangelical tradition to veer away from gossip and complaining and steer toward encouragement and rejoicing to such an extent that as a community we can end up tacitly condemning grief and lamentation, and even clear communication. This version of the power of positive thinking can affect the existence and accessibility of sources because it shapes what people preserve or destroy, what they grant or prohibit access to, and what they’re willing to talk about to a biographer.

Then, too, from the earliest medieval lives of the saints, through Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, through nineteenth-century missionary stories, and on into the present, Christians have been writing biographies with the goal of inspiring other Christians in their faith. Christian readers have been approaching these texts in search of inspiration, even reading them devotionally alongside the Bible. When research does turn up things that are decidedly non-inspirational, this habit of mind can make people deeply uncomfortable with the inclusion of this information. We want the stories to be told, but there exists the temptation to say, not like that.

Certainly, this was Elliot’s experience in writing both about her own life and about the lives of Jim Elliot, R. Kenneth Strachan, and Amy Carmichael, the missionary subjects of her full-length biographies. For each book the source material included facts that upset some of her audience—weakness and discouragement and temptation and sin. Each book reflects to varying degrees Elliot’s sense that she had to defend her refusal to “‘delicately censor’ anything at all which I felt would contribute to the faithful portrayal of the whole man.”

Ironically, having this approach as a writer did not stop Elliot from censoring some sources related to her own life. Although she kept a wealth of material, she destroyed letters from a particularly fraught time in her first year on the mission field, as well as small but pertinent portions of Jim Elliot’s journals and his love letters to her. None of us lives up to all of our principles all of the time.

Years before she was a biographer or the possible subject of a biography, Elliot wrote home from Bible school about a missionary biography she was reading, noting that “it is probably like any other biography in glossing over . . . discrepancies in character” and “spiritualizing some things which perhaps are not very deserving of such treatment.” She contrasted this approach with what she called “Biblical biography,” which “forces men into the white light of eternal Truth.”

The idea stayed with her. Twenty years later, in the preface for her biography of Kenneth Strachan, Elliot wrote:

Possibly there is no better model for biography than the Bible. There it is perfectly plain that a true understanding of the world is not to be gained by pretending that things are other than what they are. If there is good, let it not be exaggerated. If there are evils, let us see what they are, and if we will, let us bring to bear upon them the light of a Biblical faith, but let us not operate as though they simply did not exist and therefore need no redemption.

Here are riches. Christianity says that human beings as individuals and as a whole are in need of redemption, and that the God who created the universe has provided for that redemption through the life and death and resurrection and return of Jesus. When we tiptoe around sin and brokenness and grief, even if it’s because we want to inspire others or affirm faith, we deny not only the need for redemption but the possibility of redemption. When we choose to tell the truth we affirm the reality and the power of redemption—the promise that this, even this, whatever this is, will be somehow put to rights at the coming of the Lord Jesus.

Amen.

Lucy S. R. Austen is a writer and editor who has spent over a decade studying source materials on Elisabeth Elliot. She lives in the beautiful Pacific Northwest with her husband and children.

Image credit: B&H Publishing Group