A reminder for critics of homeschooling: homeschooling happens at home, and that’s important.

On October 1st, a new, less invasive homeschooling law went into effect in my new home state of Ohio. Some, like me, breathed a sigh of relief and went on with our lives. This law is still more demanding than plenty of other states, so it’s not like there’s suddenly a free-for-all. But public outcry from the usual suspects was swift. Is Ohio abandoning all standards and throwing these poor children to the wolves (aka, um, their parents)? Some certainly think so.

“It’s fascinating how Ohio is failing on education but rising in theocracy and fascism,” one person Tweeted on Oct. 7th. Another lamented “I was saying that the US needs better home school regulation after the Ohio Nazi Home Schooling group was exposed 9 months ago.” The latter incident really did happen, by the way, but I should note that it took place under the old homeschooling law, which required district superintendent’s approval for each homeschooler’s curriculum! In other words, this particular curriculum was approved by the local public school’s superintendent, folks—although, in reality, I suspect this was more of a tl/dr situation, where an overworked superintendent just signed off without reading, not realizing how much this will come back to bite him.

There is a bigger cultural picture afoot within which this anti-homeschooling sentiment fits. This summer has seen an uptick of negative publicity about homeschooling. I wrote a response, “Homeschooling and Red Herrings,” which you can read over at Front Porch Republic. My main point there in a nutshell: we should be wary to conclude that certain mournful or scandalous incidents accurately characterize all homeschoolers. Normal is boring, so the millions of functional families who homeschool will never make it into the news.

When it comes to homeschooling policy, it seems that a lot of people have much to say on the subject. But the demands for more stringent requirements from some private citizens and lawmakers ignore where homeschooling happens. The definitive aspect of homeschooling is that it happens at home.

It is right and well for the public and the public’s elected representatives to have a say in public schooling in the state, paid as it is by taxes. Homeschooling, however, involves opting out of that system for a variety of reasons, including a desire to offer one’s children a different sort of education than that available in public schools. When states try to excessively regulate homeschooling, it looks like the state trying to mold home education into a version of public education, which is really missing the whole point. If I wanted my kids to get a public-school education, I could just send my kids to the local public school, rather than replicate the same at home.

I am not here to dunk on public schools and teachers, who are public servants par excellence and provide an essential service that many families invariably do need and want. But I want to expand on what it means to opt out of the system for those who would like to do so and (no less important) have the means to do so. Public school education is, in some ways, the quintessential industrial-age factory product. Because mass-produced, it sure is much cheaper than anything individually designed and tailored would be, just as a mass-produced jacket or dress off the rack will always be much cheaper than the same product tailor-made. Yes, the general diet of math-science-English-social studies-PE that is on offer is sufficiently balanced. Like most things off-the-rack, it’s not bad, really. But parents who want something different may ask the question: what do we sacrifice through this industrialization of the intellectual lives of children? And, by the way, clearly we do sacrifice something when we opt into the system, as this new report from the Journal of Pediatrics rings in alarm in examining the “decline in children’s mental well-being” in the U.S.

At the most obvious level, we sacrifice the ability to choose what our children fill their minds with during these crucial growth and development years. And it means opting into a faster-paced industrialized educational machinery that demands that all children learn at the same time, pace, method, etc.

Public schools are able to offer a pretty good product cheaply because they scale up, as economies of scale demand that they do. This means offering a narrow set of required subjects (foreign languages and the arts are too often undervalued—too expensive and niche), packing the classrooms full (again, this reduces costs), and—because of outside demands and requirements with which teachers are required to comply—teaching to standardized tests. After all, funding for schools is contingent on high percentages of students achieving certain benchmarks on tests, with the exceptionally naive assumption that test performances accurately assess the quality of actual learning that happens.

So what happens when we opt out of this system? I cannot speak for others, and that is the point. When we put home back in homeschooling, we get to be kings and queens of just one small castle—our own. And in my home, my husband and I get to decide to teach our children subjects that are not available in public schools but which we consider important—such as Ancient Greek. Individual instruction allows us to invest more heavily in conversations with the kids as part of the learning process.

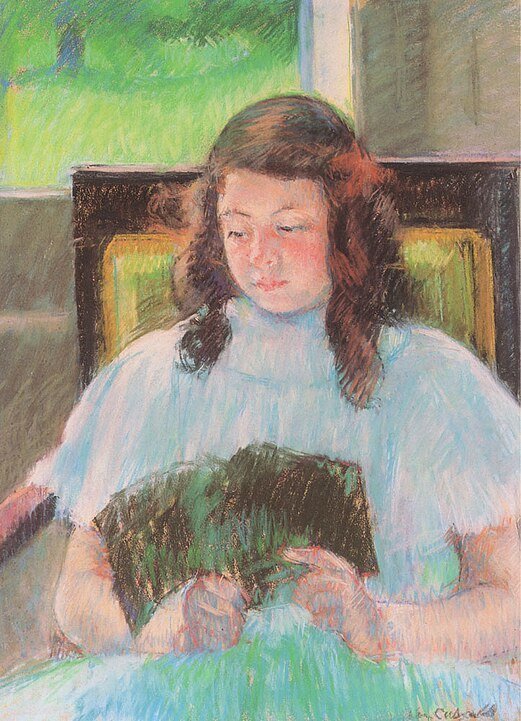

But I use the term “instruction” loosely—class time at home really doesn’t look like your typical class, first and foremost because we are, again, at home! And also, because our learning outcomes are not regular schools’ learning outcomes. How do you even objectively measure the cultivation of wonder, curiosity, and joy of learning? How do you measure the joy achieved, and the relationships cultivated over morning tea breaks with fancy cookies and a good book read aloud together? You can’t slap an assessment rubric on this.

In this modern world of ours, children and adults alike spend very little time at home. The result can be a sense of uprootedness even if, technically, one has lived in the same place for a long time. But children, in particular, need the comfort of home in their early years, I’m convinced.

My two younger kids and I spend hours each day reading books aloud and discussing them—we are currently finishing George MacDonald’s The Princess and Curdie (shout-out to Current’s Contributing Editor Tim Larsen, who kindly introduced our family to George MacDonald!). We also take regular family field-trips—both to historic sites all around and to the zoo and various parks and playgrounds. Finally, the kids spend a lot of time engaging in creative play—some of it using the massive bin of costumes and dress-up accessories that take up an entire closet. Oftentimes, the eight-year-old writes elaborate scripts for these plays, formalizing the playtime further. At times, Egyptian hieroglyphics are involved. Also, recently there has been some embroidery and the making of friendship bracelets—activities I personally abhor, so having a daughter who wants to do these things is really stretching me in the crafts area.

You may be wondering as you read this: is the end result of what we are doing better or worse than what the Williams kids would have gotten from the public schools here? Respectfully, I think this is the wrong question to ask. This is not about pursuing some form of education or curriculum that is objectively better or worse. Rather, what the kids are getting is what Dan and I think is best for them in our capacity as, first and foremost, their parents. In other words, as the ones who get to make decisions for what is best for this home, we do what we think is best for our home and in our home—rather than outsourcing these decisions to the modern educational industrial complex. Plenty of other parents would choose differently, as is their right as their children’s parents. And so, someone from outside looking in can say that what we’re doing is crazy or inadequate. Or they might be impressed. But it really doesn’t matter, because this homeschool is in my home, not theirs.

But there is more—and this really is a topic for another post sometime soon. Too often critics of homeschooling try to argue that it is bad for a democracy to have these non-traditionally educated citizens. I respectfully have a rebuttal: in this age of accelerated and unprecedented innovation and constant change (AI, anyone?) for good or ill, we need non-traditionally educated thinkers who are not afraid to think outside the box and come up with creative solutions and responses—precisely because all their lives, they have been encouraged to do this.