Public theology for different publics

This article is revised from the plenary lecture given at the Kuyper Conference on Public Theology at Redeemer University in Ontario earlier this year.

*

I begin with an epigram from an unusual sort of public theologian, the American poet Walt Whitman.

“Great poets,” Whitman said, “require great audiences.”

Among Americans interested in public theology, the question has often been asked, “Where is the Reinhold Niebuhr of this generation?” Among Reformed Christians, the question shifts, with a nod to songwriter Paul Simon: “Where have you gone, Abraham Kuyper?” Why are there no Abraham Kuypers or Reinhold Niebuhrs today?

In line with Whitman, I submit that the answer is that there are no more Kuyperian audiences.

So does this mean that there are, and can be, no more public theologians? Perhaps. But perhaps instead it just means that different public theologians are required for different publics.

But are there any publics today that want public theologians? This is the chain of questions prompting this reflection.

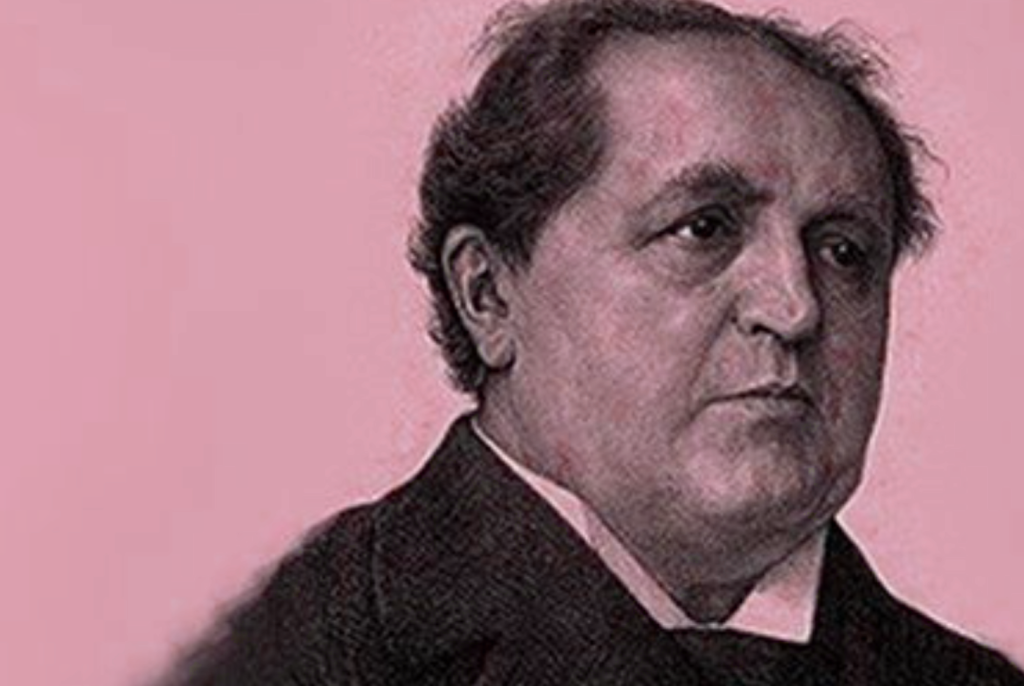

Abraham Kuyper was a man of—how to put this?—several interests. Wikipedia, the vox populi, introduces Kuyper thus:

Abraham Kuyper (29 October 1837 – 8 November 1920) was the Prime Minister of the Netherlands between 1901 and 1905, an influential neo-Calvinist theologian and a journalist. He established the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands, which upon its foundation became the second largest Calvinist denomination in the country behind the state-supported Dutch Reformed Church. In addition, he founded the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, the Anti-Revolutionary Party, and a newspaper.

So: Kuyper was a pastor who founded a large denomination; a politician who founded a political party and eventually rose to Prime Minister; a journalist who founded a newspaper; and an educator who founded a university. Kuyper was, in sum, an astonishing polymath who has inspired many from his day to our own, as he has inspired me.

He is also, however, largely irrelevant to this conversation.

To make this negative point, along with a few positive ones, requires us initially to define terms, and “public theology” in particular.

By theology I mean the articulation of the great truths of the Gospel, the Story told by the Scriptures about God in Christ reconciling the world to himself. Let us contrast this category of theology with Christian philosophy or, we might say, Christian “thought in general,” which would be Christian thinking framed and motivated by the Christian Story but directed at other subject matter than salvation per se.

A public theologian, therefore, would be someone who articulates and applies the great truths of the Gospel to matters of public moment. The discourse of such a person necessarily would make explicit reference to the triune God and the economy of salvation as revealed in Holy Scripture. A Christian public philosopher or public intellectual or public scholar would in turn be someone who participates in public discussion according to a Christian mind, but with Christian terms and categories emerging explicitly only as that conversation would require them in order to make plain that person’s meaning.

(A third category of public-facing Christian scholarship can be briefly mentioned here: expertise on Christianity. This would be the work of someone who studies Christianity as a social or cultural phenomenon: the historian, or sociologist, or literary critic, or art historian. This “officially disinterested” scholarship can, and often does, give the scholar who is herself a Christian access to the public in a strictly descriptive mode that sometimes can open into an occasion for public theology. But having noticed this category, we will now set it aside.)

The speech of a Christian public theologian, therefore, will be marked by frequent and substantive reference to the core teachings of the Christian religion. It is, after all, theology. The speech of a Christian public intellectual, by contrast, must always be consonant with the Christian Story, but it will mention distinctive Christian terms only as pertinent to the subject under discussion.

I return, then, to the irrelevance of Abraham Kuyper. Kuyper addressed a largely homogenous society—or, at least, a large largely homogeneous fraction of his society: Dutch Reformed Christians. As one reads, for instance, through James Bratt’s lovingly curated Centennial Reader of Kuyper’s work, one comes across Kuyper frequently and naturally referring to “our Dutch heritage,” “our Dutch temperament,” “our Reformed Christianity,” and “our church.” This great poet, if I may refer to him as such, required a great audience, and he had one. But that audience isn’t ours.

Canada today continues to move away from its Christian heritage. The last census sees barely half the population even claiming to be Christian, while regular churchgoing—a practice so highly correlated with every other kind of Christian practice, from regular prayer to Bible reading to tithing, that it serves as a reliable proxy for “observant Christianity”—has declined in just two generations from two out of three Canadians to under two in ten. America is experiencing similar declines in most regions of the country, as the social advantage of going to church continues to wane—even in the holdout regions of the Midwest, South, and Texas.

Think of twentieth-century public theologians still inspiring people today. Reinhold Niebuhr in the United States, yes. The courageous young Dietrich Bonhoeffer in Germany. And perhaps Canadian George Grant, who could write a Christianly inflected Lament for a Nation as recently as the 1960s.

The end of Christendom, however, has been experienced now almost everywhere. John Calvin and John Knox could be public theologians because their publics were inclined to heed what pastors said—or, in the case of the powerful, to heed the fact that many of their people would heed what pastors said. But who cares what pastors have to say nowadays?

Søren Kierkegaard is lionized now in Denmark. The last time I was in Copenhagen I took coffee in a popular shop near the university and, without making a point of it, easily spied a student with a dog-eared paperback edition of Fear and Trembling resting beside her espresso. In his own day, however, he was largely ignored by a public whose attitude toward him oscillated between indifference and irritation. One could hardly imagine a latter-day Kierkegaard attracting better press in that nation today.

John Wesley? William Wilberforce? Charles Finney? Egerton Ryerson? G. K. Chesterton? Walter Rauschenbusch? Dorothy Day? Martin Luther King? All of these figures, who addressed major public issues of their day with explicit reference to the Christian story in the Christian scriptures, addressed publics inclined to listen to people who referred explicitly to the Christian story in the Christian scriptures.

George Grant might well be the last Canadian to get that kind of attention. And the last public figures in this country who look anything like Abraham Kuyper flourished almost a century ago: William Aberhart, the Alberta radio preacher who founded the regionally very successful Social Credit Party, and the nice Baptist pastor turned quiet revolutionary Tommy Douglas, who helped found what is today the New Democratic Party and many of whose ideas—from universal employment insurance to single-payer government health care—have become so mainstream as to be linked in most Canadian minds as part of our patrimony.

One cannot function as a public theologian, however, if there is no public that wants to be addressed theologically. Great poets require great audiences.

Bonhoeffer’s government cut him off from the airwaves and cut him out of his university position when his public theology annoyed them overmuch. A content analysis of Canada’s two national newspapers, The Globe and Mail and The National Post would attest to but a trickle of identifiably Christian content in their pages as their editorial policies have tightened up over the last several decades. (Having published a number of pieces in both, I can personally attest to the near impossibility of getting anything of that sort past their editors nowadays.)

Paul Tillich once made a harsh remark about his fellow theological giant Karl Barth in the middle of the last century. Tillich—the liberal theologian’s liberal theologian—is famous for his “method of correlation,” by which he laboured to discern the leading questions of his day and then correlate Christian theology so as to answer those questions. Critics of Tillich (and I am one of them) adjudge Tillich to be far too willing to conform, not merely correlate, Christian thought to the categories and agenda of this present age. But Tillich properly looked askance at Barth who, he felt, bothered far too little to listen to the concerns of his time and respond in a way intelligible to his contemporaries.

Barth’s one venture into public theology, as it were, was the Barmen Declaration. It stopped at merely asking the state to let the church freely preach the gospel—a stopping point, if I recall correctly, that infuriated Bonhoeffer, who judged that the moment required also a statement asserting solidarity with the Jews persecuted by the Reich. Fairly or not (and Barth’s legions of supporters will bristle at the charge), Tillich condemned Barth as having culpably ignored the concerns of his fellows and instead to have merely hurled the gospel at the world “like a stone.”

How, then, can North Americans who want to bring the great truths of the gospel in particular, and a Christian mind in general, to bear on the issues of our day do so in such a way that at least some members of the public will actually pay them heed?

First, in this era of multiple streaming services and other video sources (instead of a few major TV networks) and countless journalistic websites (instead of a few dominant newspapers and magazines), we are all aware that there is not just one public. Millions of Christians remain in both countries who, one supposes, might at least be open to opinion couched in Christian language. Abraham Kuyper turns out to be relevant to us after all, as he can aspire people to address such publics.

The huge problem here, however, is that the worst Christian speakers are full of passionate intensity while the best . . . well, where are the best? To whom do our best thinkers and communicators prefer to address their thoughts? And how do they do so? Few, few, few of the latter are even attempting to address anything like a general Christian public, preferring instead to talk to each other in clever magazines and blog posts whose very graphics, let alone vocabulary and syntax, serve immediately to signal, “Only smart people welcome.”

Abraham Kuyper, by contrast, had the successful preacher’s gift—the successful politician’s gift—of speaking plainly and interestingly to a general audience. We need many more today who will get free of the compulsion to impress their fellow scholars and serve a wider public that is mostly at the mercy of well-meaning but incompetent amateurs and cynically exploitative demagogues.

Positive examples come to mind, such as Charles Camosy, a Roman Catholic scholar with powerful political arguments about abortion legislation; Kathryn Hayhoe, an evangelical scholar campaigning against catastrophic climate change; Robert George and Mary Ann Glendon, Ivy League worthies offering bold ethical opinions; and Charles Taylor, who not only explains our culture, albeit at intimidating length, but who has frequently also rolled up his sleeves to help change it, as in his participation in the landmark Bouchard-Taylor Report on “reasonable accommodation” of cultural differences in Quebec.

To turn immediately to another well-known Canadian, Jordan Peterson, will be jarring for some. But he can serve as an instructive example, both positively and negatively. Dr. Peterson, so far as I can tell, has deserved his full professorship in clinical psychology at one of Canada’s premier universities. Alas, his self-confidence has prompted him to say embarrassing things about subjects clearly beyond his ken, whether postmodernity or Christianity. He has become impressively popular in critiquing truly silly and sometimes dangerous wokeness on campus (Amen) and in offering practical truisms to young men based largely on Christian values but secularized into Anglo-Canadian decency and self-respect, a sort of male version of Girl, Wash Your Face: Dude, Clean Your Room!

We need such simplicity and verve. But we need wisdom emerging from an impressive, pertinent knowledge base and not merely from a lone guru working out of his depth. Better still, we need such wisdom to emanate from a strong community that actually practices such wisdom.

Thus my second point. Apologetics, evangelism, and public discourse about Christianity in North America today will emerge most winsomely from communities practicing what we preach. The Salvation Army, A Rocha, World Vision, the Christian Labour Association of Canada—these and many more are institutions that show more than they tell, and spokespeople identified with such good works will be welcomed to explain and advise out of the integrity and effectiveness of their mission. We need strong corporate expressions of our religion—and particularly local congregations, not just these special purpose groups—before anyone will want to listen to any of us as individuals.

Third: Successful public theology today must be bilingual in ways Kuyper never had to be.

Public theology needs to be bicultural, “biracial,” “bi-ethnic.” The public theologian has to truly get it, and get both its: the Christian community and the community he or she addresses. This is a matter of effective translation, and translation can be done well only with a strong combination of intuition and analysis: true empathy, and, ideally, sympathy.

To use Kuyper’s own categories, there must be enough commonality of culture (“common grace”) or there will be irrelevance: of concern, of argument, and of expression. There must also, however, be enough counter-culture (“antithesis”) or there will be mere redundancy, a slightly accented repetition of what is already being said.

Christian communities—and especially churches and schools—must think carefully, then, about how to foster both strong Christian commitment and a genuine immersion in the non-Christian culture they are addressing. It cannot be enough merely to look out at the world from the safety and reinforcement of our enclave to note this or that information about the world and then try to reply to the world on the basis of that conscientious study. To truly communicate, we have to be in the world, to be sent into the world, as Jesus himself sends us (John 17), so that we naturally feel what they feel and can discern what they may want to hear about the Word of Life.

As a parent of young men educated in Canadian public schools and in Canadian public universities, and as a graduate of and former professor in two of those universities myself, I am well aware of the peril, poison, and sheer puerility of so much that goes on in such places—as in Canadian public life in general. Having lived in the United States for more than a decade and as a graduate of one of its better secular universities, I feel confident making a similar observation about American culture as well.

Missionaries, however, recognize that there is no substitute for genuine cultural immersion, however challenging. And we are all missionaries now.

Are we in actual conversation with, because living life with, a public beyond the Church? Hurling the Word at the world isn’t engaging in public theology but merely virtue-signaling to one’s own constituency.

Fully forty years ago Francis Schaeffer’s protégé Os Guinness was already reaching back to Erasmus’s In Praise of Folly to tell us that North American culture would no longer sit still for straightforward presentations of Christian truth. We would have to take “oblique” approaches, Guinness suggested, looking for entry through side doors, since the front doors were generally barred against orthodox Christianity.

One thinks of Emily Dickinson’s famous poem suggesting that God himself accommodates his revelation to our capacities, and so we should to each other’s:

Tell all the truth but tell it slant —

Success in Circuit lies

Too bright for our infirm Delight

The Truth’s superb surprise

As Lightning to the Children eased

With explanation kind

The Truth must dazzle gradually

Or every man be blind —

What was true in Dickinson’s day is all the more true in ours. We are the most educated generation in world history, and yet what purchase does any form of rational argument have on us nowadays? How much interest is there in reasonable discussion of religion: in arguments based on evidence that might come to challenging conclusions?

Twenty years ago I spent over an hour on the phone with the editor of The Atlantic, Cullen Murphy (himself a Roman Catholic) about why his magazine, and others like it, would not—and would never, he avowed—publish a presentation of Christian theology, no matter how graciously and wittily presented. His readers, Murphy said, wouldn’t be interested. Yet in the pages of that very magazine appears today sub-Christian, unorthodox theology. Harvard’s philosopher of happiness, Arthur Brooks, for one egregious example, serves up sunny, but startlingly superficial, mashups of Thomas Aquinas and the Buddha. (I pause to note that those two great thinkers in fact disagree about almost everything.) This intellectually deficient syncretism somehow passes muster while an informed and articulate case for, say, the historical reliability of the Gospels or the enduring wisdom of Christian sexual ethics would be spiked immediately by whatever intern was assigned it from the pile.

Perhaps our culture may just have to outwait the Boomers and their sustained antipathy to the Christianity of their parents. Thomas Kuhn advised us (in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions) that the way paradigms finally shift is that young people with new ideas just wait for old people with old ideas to die off. Young people who are not committed Christians—whom I teach in considerable numbers as undergraduates at my university—I find to be either indifferent to or genuinely interested in Christianity, even if their parents are still either strongly pro or con. Maybe in another twenty or thirty years—although, I would suggest, already in Vancouver, Seattle, and Portland, and other quite secularized parts of North America—Christians can start to speak in public again on the same footing as everyone else.

Meanwhile, however, what to do—and who to do it?

North American publics will indeed sit still for, and even welcome, moralistic address, even explicitly Christian address, so long as it comes in the right modes. What modes?

Consider novelist Marilynne Robinson, who has done more to promote Calvinism in America than anyone since, well, Cotton Mather.

Consider New York Times journalists David Brooks and Ross Douthat—and even The Atlantic’s winsome James Parker, who sneaks in a bit of genuine Christian content every once in a while.

Consider comedians—the public speakers who chide and even hector their audiences on the moral vexations of our time, whether Dave Chappelle or Hannah Gadsby, Chris Rock or Ricky Gervais. In the midst of this chorus of voices generally hostile to Christianity, Christian Jim Gaffigan keeps succeeding as a nice Catholic man who gently makes powerful moral observations along the way. So does Stephen Colbert.

Filmmakers—from major motion pictures to TikToks, from Denzel Washington to, perhaps, your daughter. Can Christian terms, concepts, and values translate to the screen? Sometimes pretty well and pretty explicitly—from Chariots of Fire to The Chosen—but more often obliquely also.

And what about poets? Canada is not an especially poetical country. Aside from our great Margarets, perhaps, our best poetry is in song lyrics—Leonard Cohen, Bruce Cockburn, and such. Our southern neighbours, however, feature many thoughtful Christian songwriters—especially in country music and hip-hop, the two genres in which lyric writing matters most.

And maybe even the occasional graphic artist. Even artists—as suggestive and allusive and implicit as they necessarily are—might still somehow function as public theologians, especially if they possess the additional gift of cogent writing and speaking. Such polymaths win audiences not interested in run-of-the-mill theologians and can say Christian words to them.

I have American Makoto Fujimura and Englishman Roger Wagner in mind. There may not be many such, but we should celebrate them when we find them. For we need alternative languages in which to address North Americans today—most of whom think they already know what Christianity is and have made up their minds about it, when poll after poll demonstrates that most North Americans’ actual knowledge of Christianity is diminutive and distorted.

We need lots of kinds of public theologians and lots of kinds of public intellectuals to present lots of kinds of messages in lots of kinds of modes to lots of kinds of publics. Perhaps, then, the Niebuhrs and Kuypers yet flourish. They’re just speaking on their own channels to their particular publics.

How will you properly address yours?

John Stackhouse holds the Samuel J. Mikolaski Chair of Religious Studies at Crandall University in eastern Canada. His most recent books are Can I Believe? Christianity for the Hesitant and Evangelicalism: A Very Short Introduction, both from the Oxford University Press.