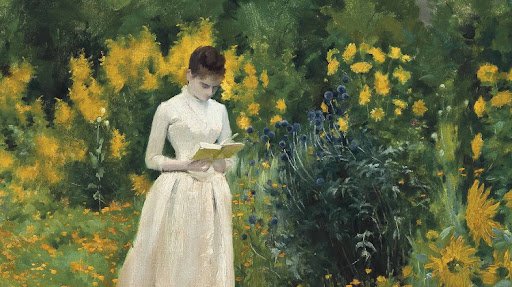

You know them. You may be one of them. They are people who seem perfectly sociable at times but get drained and go quiet after prolonged time in large groups. Left alone, they delight in books, have robust conversations with the ideas in their head, and wonder how everyone else can live with so much external noise, bright lights, and stimulation. It’s not that they do not like people—they are no misanthropes. Rather, they love people more when they are not around them every waking minute. Here are two examples.

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2014, one middle-aged man living alone with his beloved bees in the “grey zone” officially belonging to neither Russia nor Ukraine, had a hard decision to make: “He could have lived out his days in that way, but something intervened. Something broke in the country, in Kyiv, where nothing had ever been quite right. It broke so badly that painful cracks ran along the country, as if along a sheet of glass, and then blood began to seep through these cracks.” He decided to stay put in his village. Others, however, evacuated—not all at once, perhaps, but over time. And so, one day this man discovered that he was the last one left in his village, except for just one other man, on another street. Remaining in his own lifelong abode, each man matter-of-factly chose to continue his solitary existence in this new apocalypse.

Another man, slightly younger, found himself unexpectedly, with no recollection of how he even got there, in a strange house with many rooms. It seemed infinite, ever-growing, but also ever joy-giving. And while there were vestiges of previous inhabitants, some of them mere bones packed in boxes, this man appeared to be the only living human inhabitant of the house—with the exception of one other man, the Other, whom he met twice a week for just one hour, strictly timed.

These are the basic plot summaries, respectively, of two novels, each of them lovely yet heartbreaking in its own way: Andrey Kurkov’s Grey Bees (masterfully translated into English by Boris Dralyuk—it is from his translation that I quote above) and Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi. But what connects these two very different novels in my mind is this unlikely commonality: each one, in its core, celebrates the rich inner intellectual and spiritual life of introverts who find themselves living alone in crisis, even if not entirely by their own choosing. Each one finds joy in this unusual existence, even if it is not an easy joy. Sergeych, after all, is living in a horrific war zone–prefiguring the war ongoing in Ukraine right now. Piranesi, similarly, is a victim of a cruel experiment, even if he has no recollection of it for much of the book.

And yet, in both cases, we see the wired-in human impulse to love, steward, take care of other living things, rather than merely surviving all alone. Kurkov’s Sergeyich protects his bees, the long-suffering victims of the war, who do not understand that things such as wars exist and interrupt their natural impulse to do the one thing they have been designed to do—make honey. Likewise, Piranesi stewards the mysterious house, the birds living in it, and the beautiful statues decorating it. He feels a sense of responsibility for the well-being of the house and all within it, flesh feathered or marbled alike.

There is something cosmic about this. The first human, Adam, was all alone at first, aside from the animals and the various growing things in the garden, whose steward he was created to be. But what is striking is that he himself did not realize that perhaps he was not well off simply living life alone, taking care of other non-human life forms. It took God’s observation to realize that each person needs to live in relationship with other persons. We are not well otherwise.

This is a useful reminder for all of us, and especially the introverts among us, in our ever more digital and fragmented world with its disrupted in-person relationships. It is well and good for us to take care of our world, protect the beauty of creation in all its non-human forms, and yes—even delight in our ideas and time alone. But people—family, friends, neighbors, and others God brings into our lives for reasons that sometimes we may not even fully understand—are our responsibility, and as the CDC agrees right along with Genesis, stewarding them is for our own good too.