Robert Fleegler is Associate Professor of History at the University of Mississippi. He is the author of two books, Ellis Island Nation: Immigration Policy and American Identity in the Twentieth Century (Penn, 2013) and Brutal Campaign: How the 1988 Election Set the Stage for Twenty-First Century Politics (UNC, 2023). Today he visits the Arena to tell about his next project!

What is the focus of your current book project? What are the big questions that you are investigating and the main stories that you hope to tell in this book?

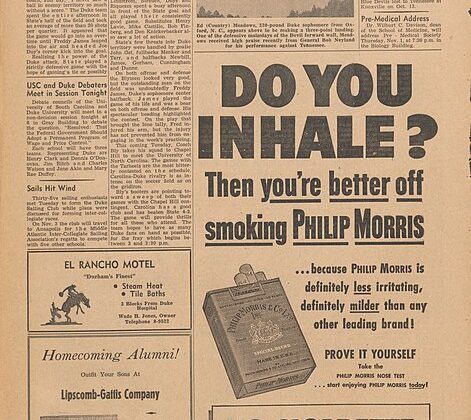

My current book project is focused on the politics of the changing attitudes toward smoking between the release of the Surgeon General’s report in 1964 and the passage of comprehensive anti-tobacco legislation in 2009. In particular, I want to delineate the process by which a strong anti-smoking culture emerged in this time frame. We went from a world in which smoking was a commonplace activity—1/3 of Americans still smoked as recently as the 1980s—to one in which it is a stigmatized activity and only 1/10 of Americans smoke. This shift came about in large part due to efforts by local, state, and the federal governments to combat smoking.

Notably, Dr. C. Everett Koop, President Reagan’s Surgeon General, used his bully pulpit in the 1980s to educate the citizenry about the dangers of smoking and his tenure will likely be a key focus point. During this time, studies showing the dangers of second-hand smoke shifted the debate away from one merely of personal choice to a broader public health concern. And as predicted years earlier by Koop, this led to the widespread segregation of the remaining smokers, who can only smoke in a few isolated places today. And once a broad-based activity conducted by a cross-section of Americans, smoking has become concentrated largely among working-class and poor people.

Can you give us a taste of something intriguing or unexpected that you have found in your work on this project so far?

I think the most interesting thing I have discovered and rediscovered is how permissive an approach we had toward smoking not so terribly long ago. A half-century ago, anti-smoking legislation merely meant laws to mandate non-smoking spaces in certain public areas such as restaurants. In the late 1970s, anti-smoking referendum twice failed in California, of all places. Even voters in San Francisco barely passed anti-smoking legislation in the early 1980s. In the late 1990s, Bill Clinton and John McCain pushed anti-tobacco legislation that seemed on its way to passage but eventually failed after relentless attacks from Big Tobacco.

High schools once designated areas for students to smoke. Planes featured smoking and non-smoking sections for years in an enclosed space where fumes were inescapable; Congress did not pass a ban on all smoking on flights until the late 1980s. Movies of that time still often featured smokers in heroic roles, like John McClane, the Bruce Willis character in the “Die Hard” films. It just seems so bizarre now.

In what ways is this story that you are telling political?

I think what is interesting is how successful the tobacco companies were in blocking strong anti-smoking bills for so long. They routinely used ad campaigns to transform public health measures into attempts by big government liberals to control citizen’s lives in the eyes of the public. In that sense, they tapped into the conservative tide of the Reagan years and beyond. Though some Republicans such as Utah Senator Orrin Hatch were strong anti-tobacco crusaders, the Democratic Party—led by liberals like Senator Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts and Congressman Henry Waxman of California–usually initiated these campaigns. Blue cities and blue states also led the way in regulating smoking.

In doing so, Democrats often placed themselves at odd with key constituencies of their base, as African Americans and working-class whites smoked in higher percentages than most demographic groups. Indeed, the tobacco companies made significant efforts to support black institutions to buttress their support in the African American community. It also reflected the post-McGovern shift of suburban voters into the Democratic Party and how their concerns might be different than those of the old New Deal coalition.