O Captain! my Captain! our fearful trip is done,

The ship has weather’d every rack, the prize we sought is won,

The port is near, the bells I hear, the people all exulting,

While follow eyes the steady keel, the vessel grim and daring;

But O heart! heart! heart!

O the bleeding drops of red,

Where on the deck my Captain lies,

Fallen cold and dead.

O Captain! my Captain! rise up and hear the bells;

Rise up—for you the flag is flung—for you the bugle trills,

For you bouquets and ribbon’d wreaths—for you the shores a-crowding,

For you they call, the swaying mass, their eager faces turning;

Here Captain! dear father!

This arm beneath your head!

It is some dream that on the deck,

You’ve fallen cold and dead.

My Captain does not answer, his lips are pale and still,

My father does not feel my arm, he has no pulse nor will,

The ship is anchor’d safe and sound, its voyage closed and done,

From fearful trip the victor ship comes in with object won;

Exult O shores, and ring O bells!

But I with mournful tread,

Walk the deck my Captain lies,

Fallen cold and dead

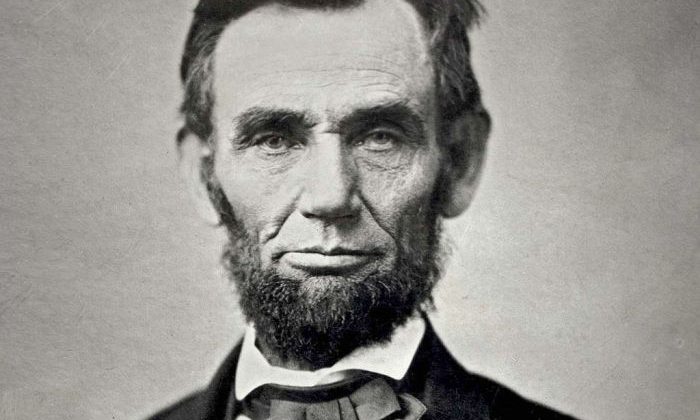

You cannot read Walt Whitman’s poem for Abraham Lincoln without noticing how much he loved Lincoln and respected him. Lincoln was celebrated for seeing the ship “anchor’d safe and sound.” He deserved flags and ringing bells and “bouquets and ribbon’d wreaths.” Why? Because he was not just a victor, he was considered good.

In recent years, we’ve had a lot of people accusing other people of “virtue signaling.” Everyone is aware that attempting to show off being ethically superior is annoying and wrong. But the accusation is thrown around so easily, it seems like it’s almost become negative to be associated with virtue. In some circles, it probably is. It has become embarrassing to be winsome among some people. Pursuing virtue might be equated with giving up on “winning” in some contexts. Think of all the people on Twitter/X who have “deplorable” in their handle—they don’t argue that their candidates and positions are not deplorable, they embrace being deplorable.

In Growing Up Absurd, Paul Goodman lamented that a young person in his time would almost certainly not grow up hoping to serve their country in some way, seeking to be the kind of person who we’d want to have a statue for. You might say that’s true because we’ve taken to tearing down statues, but we started tearing down the kind of image and service that comes with statues long ago. It’s one thing to wrestle with knowing that the people we’ve memorialized were imperfect, it’s another to suggest that we ought not to have any expectations for people on pedestals.

Unfortunately, that seems to be where some of us are. And when we’re choosing current leaders for ourselves, we speak as though it’s naïve to want anyone who is at least attempting to be closer to perfect. “Well, what are you going to do? They’re all crooks.” “You really think trying to save the environment is worth it?” “Everyone everywhere is miserable, oh well.” One reason we can’t have statues is because we don’t understand how to confront our past, another is because we’ve become cynics. We’re not the kind of society that encourages people to do the kinds of things that get remembered in marble.

It’s too bad. Our culture could value honor much more without becoming completely an honor culture. We probably won’t end up with more virtuous citizens when we’re looking to shame others for “virtue signaling” any chance we get. In The City of God, St. Augustine acknowledged that chasing after honor is a vice. But he believed that it was a vice which could prevent other vices. The attempt to be virtuous and to be honorable can prevent people from doing bad things. If we celebrate rather than shame goodness, if we appreciate virtue when we see it, if we respect innocence when it exists, we’ll probably be a little happier in the public square.

As much as we roll our eyes at other people’s attempts to do good, we crave good examples. Watch how people tear up in sports movies when the hardworking team triumphs. Watch how they enjoy all the Captain America movies and buy t-shirts that represent him. Talk to anyone who has read The Boys in the Boat. But we have a really hard time translating that into everyday life. We don’t want our kids to major in social work and be poor but virtuous. We don’t want to vote against our party because of our conscience. And we don’t want to be held accountable or judged poorly for our own bad behavior. We want to win. We want to be comfortable. We want to have no reason to doubt our own goodness. If anyone notices something bad about us or questions our choices, we just jump on the “what about” train. It calls at all stations.

What a shame. We need virtue. Democracy depends upon it. Sure, James Madison said “if men were angels, no government would be necessary.” But the Founders still attempted to cultivate a republic built on virtue. They idolized ancient Rome, where the virtues were celebrated. Men like Washington upheld figures like Cincinnatus. Hamilton’s affair mattered because they believed in honor back then. The Founders believed in public virtue and they encouraged it. They even believed in manners. George Washington wrote a whole pamphlet on civility.

The remedy is not to idolize everyone from the past or to hide all our imperfections. But we can celebrate those who pursue virtue, who seek to do better. This is the argument of Jon Meacham’s The Soul of America. The conclusion we should draw from the flaws of famous men is not that it’s silly to care about flaws. It’s that we should most appreciate those who struggle against their imperfections.

Let us return to Abraham Lincoln. As stirring as Whitman’s poem is, it is perhaps more stirring to hear Copland’s “Lincoln Portrait,” here with a solemn Carl Sandburg, or here with a rousing Melvyn Douglas. Over the music, these words are recited:

“Fellow citizens, we cannot escape history.”

That is what he said. That is what Abraham Lincoln said.

“Fellow citizens, we cannot escape history. We of this congress and this administration will be remembered in spite of ourselves. No personal significance or insignificance can spare one or another of us. The fiery trial through which we pass will light us down in honor or dishonor to the latest generation. We, even we here, hold the power and bear the responsibility.” [Annual Message to Congress, December 1, 1862]

He was born in Kentucky, raised in Indiana, and lived in Illinois. And this is what he said. This is what Abe Lincoln said.

“The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty and we must rise with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves and then we will save our country.” [Annual Message to Congress, December 1, 1862]

When standing erect he was six feet four inches tall, and this is what he said.

He said: “It is the eternal struggle between two principles, right and wrong, throughout the world. It is the same spirit that says ‘you toil and work and earn bread, and I’ll eat it.’ No matter in what shape it comes, whether from the mouth of a king who seeks to bestride the people of his own nation, and live by the fruit of their labor, or from one race of men as an apology for enslaving another race, it is the same tyrannical principle.” [Lincoln-Douglas debates, 15 October 1858]

Lincoln was a quiet man. Abe Lincoln was a quiet and a melancholy man. But when he spoke of democracy, this is what he said.

He said: “As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy. Whatever differs from this, to the extent of the difference, is no democracy.”

Abraham Lincoln, sixteenth president of these United States, is everlasting in the memory of his countrymen. For on the battleground at Gettysburg, this is what he said:

He said: “That from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion. That we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain. That this nation under God shall have a new birth of freedom and that government of the people, by the people, and for the people shall not perish from the earth.“

This is not just civil religion. Our past celebration of Lincoln has sometimes veered into the unrealistic and ahistorical. But his words themselves can be part of our present remedy as we ponder our past and the future. “No personal significance or insignificance can spare one or another of us. The fiery trial through which we pass will light us down in honor or dishonor, to the latest generation. We – even we here – hold the power and bear the responsibility.” Will we be remembered in honor or dishonor? What will the future think of a generation too “wise” for virtue? Too busy being successful to stand on honor? Cynics do not leave much of substance.

Lincoln was right, we cannot escape history. We will be remembered in spite of ourselves. Wouldn’t we rather run the risk of being unrealistically celebrated by doing some praiseworthy deeds? Wouldn’t we rather be virtuous fools than angry and empty? We here, hold the power and bear the responsibility.