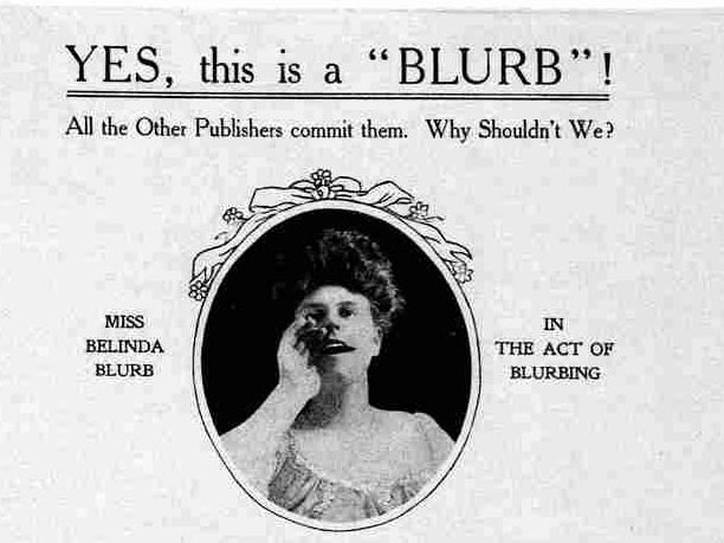

Over at The Atlantic, Helen Lewis addresses the practice of book blurbs. Here is a taste:

And that reveals another dirty secret of the blurb: They’re not addressed to you. “The biggest thing to understand is that blurbs aren’t principally, or even really at all, aimed at the consumer,” Richards told me via email. “They are instead aimed at literary editors and buyers for the bookstores—in a sea of new books, having blurbs from, ideally, lots of famous writers will make it more likely that they will review/stock your book.”

That’s the magic. Stephen King is well known for his generous praise for less commercially successful authors—which is to say basically all of them—and if he says this is an important book, then it is one. His approval is a signal as powerful as a publisher announcing that it has won a “seven-way” auction or paid a “six-figure sum.” Anointed by greatness, maybe such a golden title will be chosen by Reese Witherspoon’s book club. Maybe it will pick up chatter on TikTok or Instagram. Maybe it will become the title that everyone seems to be talking about, like Yellowface or Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow. Blurbs are therefore an uneasy hybrid of quality-assurance mark and publicity gimmick. This makes the practice of blurbing a fraught one. Are you doing a fellow striver a good turn, or acting as a gatekeeper of excellence, making sure that only the best books succeed?

Reading a book takes time, so writers have an incentive to blurb only their friends. Writing a good puff quote takes time too: If you ever see the words inspiring and illuminating, assume the blurber hasn’t even cracked the spine. Most established authors are bombarded with proofs, accompanied by heartstring-tugging notes from editors about the importance of this author’s vision. After writing my own book on feminism, I could have made a fort out of advance copies of other books with women in the title sent to me by hopeful publishers. I can only imagine the number of books Stephen King receives; it must be like a snowdrift on the wrong side of his front door. The distinguished classicist Mary Beard announced a few years ago that she was declining all requests, because she felt like she was becoming a “blurb whore” after being asked at least once a week. “I’m beginning to get a lot more authors who say, I can’t do it,” Mitchinson told me.

Read the entire piece here.

When a publisher asks me to write a blurb I usually say yes. But I am not going to offer effusive praise for a book that is not worthy of effusive praise. A few years ago a religion author asked me to blurb his book. After reading the manuscript I concluded that I could not completely endorse the book’s argument. I wrote a blurb anyway. I mentioned my disagreement with the book’s thesis, but focused on why the book was important. I don’t think the author or the publisher knew what to do with it, but in the end they used it. My blurb was tucked-away conveniently on the first couple of pages of the text rather on the back cover. Maybe they were hoping no one would find it there. 🙂