Kaitlyn Schiess offers what Christians need: a better understanding of scripture and politics

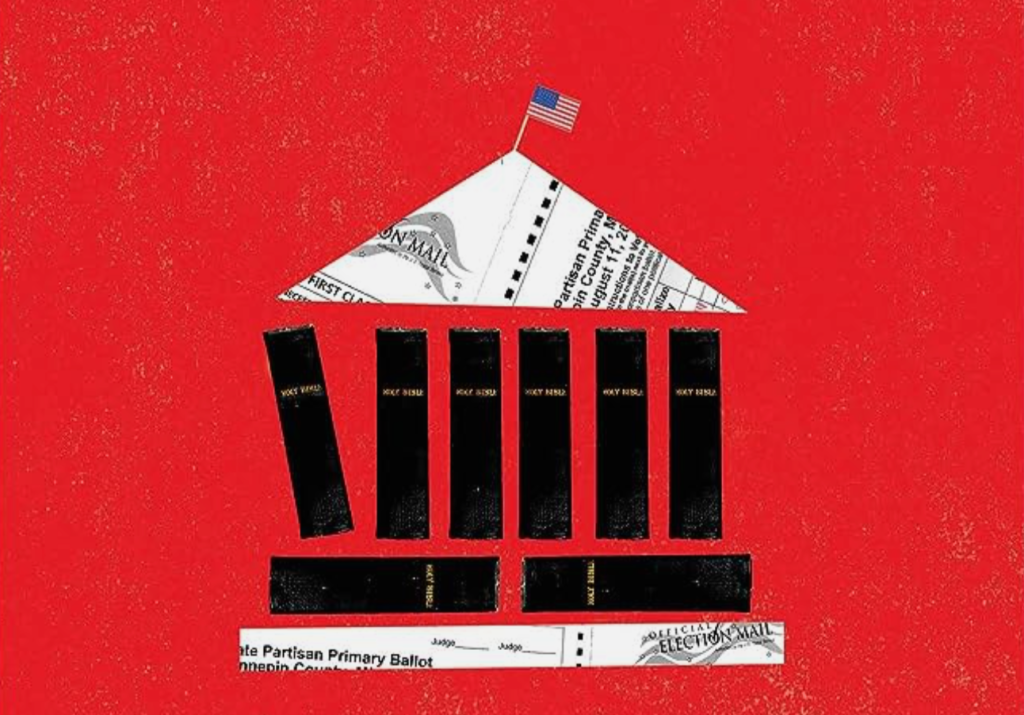

The Ballot and the Bible: How Scripture Has Been Used and Abused in American Politics and Where We Go from Here by Kaitlyn Schiess. Brazos Press, 2023. 224 pp., $19.99

It was destined to be an iconic image. In the middle of the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, President Trump ordered that a crowd in front of the White House be violently cleared away so that he could pose in front of a church holding a Bible. Using this image to open The Ballot and the Bible, Kaitlyn Schiess asks a key question: In our politics, do we tend to use the Bible as a prop? Or does it truly inform how we exercise political power?

To answer this, Schiess examines American history through the lens of various biblical passages and interpretations, ranging from the Puritan “City on a Hill” to Rev. Dr. King’s imperative to “Let justice roll down like a river” to Jerry Falwell Jr.’s use of “Render to Caesar.” Through these texts she shows how American politicians, activists, pastors, and theologians have interpreted the Bible, and how they used those interpretations to persuade or manipulate the voting public. Looking at this history has applications for Christians who are seeking to engage in biblical interpretation and faithful politics today.

Schiess offers several helpful hermeneutical tools for thinking about the use of scripture in the realm of politics. Most important is allowing the text to form us rather than simply proof-texting or superficially sampling biblical language. It is easy to pull Bible verses out of context rather than reading the entire story of Scripture and understanding a given verse within it. Schiess refers to this tendency as making “repeated and insistent references to the words of the text, as if they were easily or automatically self-interpreting.”

Lately I have been reading Deuteronomy, Isaiah and Revelation. Each of these books has a very specific place within the whole story of the Bible; each has been misused out of context. Since the Bible has formed so much of the American cultural tradition—not to mention its formative impact on the English language—it is easy for politicians and others to use the language of scripture to lend their words moral authority without doing any work to think about how their principles fit with scripture. Schiess points out that even President Biden does this, such as when he uses Isaiah 6:8 (“Here I am, Lord, send me”) to refer to American military service.

The second useful tool Schiess gives us is encouragement to interpret scripture in community—particularly in communities with deep histories and with marginalized Christians. This is clearest in her chapter on the American Civil War, where Schiess discusses white Christians’ theological and interpretive arguments for and against slavery. These white Christians attempted to find “timeless, universal principles” to defend their positions, and went to great lengths to do so. Black Christians, with a different frame of reference, had no trouble seeing themselves within the biblical story as those who were oppressed and whom God was going to liberate. With the advantage of historical distance, we can see how the former mode of interpretation misled even abolitionist white Christians who would have benefitted from listening to Black voices. That epistemological privileging of marginalized voices is still valuable to Christians as they think about political theology.

Schiess spends more time pointing out how conservative Christians have misused the Bible than progressive Christians. She demonstrates how people have twisted scripture to justify bad policy, from the Civil War to senseless hermeneutical defenses of small government. Some of this may simply be a clear-eyed view of who her audience is: Conservative Christians are more likely to be concerned with biblical interpretation than progressive Christians. This requires her to speak more prophetically to them. Still, she doesn’t limit herself to attacking the right but includes some clear critiques, for instance, of the social gospel and of President Obama.

For that matter, divisions like “right” and “left” make little sense for some of the history she tells: For instance, in the division between the rebels and the loyalists in the American Revolution, who were the conservatives? But since contemporary conservative American politics is much more obsessed with Christianity—one might consider Vice President Pence’s entire campaign pitch, for example—her critique shows the limitations of that approach in particular.

Unfortunately, the breadth of the ground Schiess covers means that this book remains a preliminary venture into political hermeneutics. She can’t dig deeply into the details of any particular scriptural interpretation since she is trying to cover all possibilities. As a follow-up to this book I’d love to read more in-depth reflections from her about, say, immigration and how Scripture speaks to it. Rather than simply saying, “The opposite of cherry-picking Bible verses is not separating theology from politics. Rather it is doing good political theology” (italics in the original), I’d love to read an in-depth response from her to a specific contemporary conversation, whether on the debt limit, climate change, or police accountability. That isn’t the book she’s writing here, but maybe it’s a recommendation for the next.

The book is also overly conceptually complex—Schiess is trying to write history, hermeneutics, and political theology all at the same time in under two-hundred pages. She does a great job, but it’s a lot to cover and means that each of the elements is a little underserved. On the positive side, that means that her references are incredibly helpful for someone trying to dig deeper. From her discussion of the history of Black American hermeneutics to her exploration of Augustine, Calvin, and Bruggeman, she paints a clear road ahead for those interested in learning more.

In spite of some powerful and helpful references to Augustine, Calvin, Bonhoeffer and other non-American figures, Schiess primarily limits herself to American source material, which helps because she already has entirely too much to cover in a brief text. But it unfortunately means that she skips some texts of obvious relevance for political theology, such as the reference to two swords in Luke 22, or Moses’s delegating of political authority.

I learned a lot from The Ballot and the Bible and took it as a clear warning. Schiess provides a series of helpful tools as guides for interpreting scripture and some important historical context for how scripture has been used and abused in the past. President Trump was cartoonish and immoral when he stood in front of St. John’s at Lafayette Square brandishing a Bible. But this book serves as a reminder that I too need to be careful when using scripture to make political points, and make sure that I am not doing the same thing with a better façade.

Greg Williams works in digital politics for a more just world. You can yell at him on X, or Threads for that matter, @gwilliamsster but he’d prefer if you were kind.