Oh, did Brother Jerome drive me nuts.

Jerome Cox, F.S.C., was a friend of my father’s from their days in the Christian Brothers junior seminary in Glencoe, Missouri. Their years together in the juniorate were formative for both of them, although my father was dispensed from his vows while he was in graduate school in the 1970’s, and the bonds between them were strong, although they only saw each other once every few years. The seminary had educated them both joyfully and, sometimes, harshly: in later years, when Jerome carved a pair of hands to symbolize two of the teachers there, he carved one as an open hand and the other as a fist.

Brother Jerome himself was also much like these carvings. He had an open-handed personality, and it was this “hand” that was dominant: he was always smiling, often chuckling gently, and thought constantly of how to become a better teacher. He also daily turned out artistic works of exquisite design and detail in the little jewelry workshop he kept in the attic of the Italian villa where he spent his summers (with special permission from his order). He was greatly moved by beauty and spiritual experiences.

But he had a closed “hand,” as well: he was an old-school authoritarian, clerical in his outlook, and his response to his female apprentices’ complaints that he kept them working after hours was to blithely quote the old saw, “A woman’s work is never done.”

Although to be fair, his own work never seemed to be done, either.

Jerome had many little foibles to go along with his fundamental generosity and artistic spirit. He watered down his wine but did like to get a little buzzed, and when he was in his cups he could be bit harsh. After one of our tangles over his lack of safety standards, he pointed his finger at me over a glass of wine said, “Don’t you tell your dad I didn’t keep you safe! That’s not true!”

I arrived in Italy for my summer with Brother Jerome fresh from my first year of college and completely starry-eyed about the prospect of three entire months working as one of Jerome’s apprentices in his Tuscan workshop. Jerome was a talented artist and teacher whose specialties were statues and rings, both of which were created through lost-wax casting. He had passed through my California hometown while I happened to be home from college for a week that spring and had offered me, the daughter of his friend, a fair deal: come work construction for me on the villa, and I will teach you to make jewelry and give you room and board and twenty Euros of pocket money per week.

I was very independent-minded and had been on adventures before, so I jumped at the chance. I bought my ticket, packed very light (“you can get your work clothes here from the pile in the attic,” Jerome had said, and indeed I did) and headed to Italy almost as soon as classes were done.

The other apprentices, with the exception of one Iowa farm boy, were in their twenties and were all art students from Ireland whom Jerome had met while traveling about, selling his jewelry. We all got on fine and had lots of fun biking down to the swimming hole on the weekends and drinking Guinness in the local bars most evenings of the week.

Well, they drank Guinness. I did not particularly care for it and just went along for the break and the conversation. Later, the other apprentices would drink the watered-down wine with Jerome on the villa balcony and we’d all have a “sing-song” together. I learned to play the bodhrán (an Irish drum), and a pair of kind booksellers visiting from Cork gave me two Irish songbooks which I still use today.

We needed all this conviviality, and not just because the work was hard, both the fine-detail work of polishing and finishing Jerome’s jewelry and the heavy physical labor of tiling floors and installing electricity. It was also because we, the apprentices, and Jerome, did not understand one another. And of all of us, Jerome and I were the worst pair of all.

It all started when I was making a couple of dozen wooden screened windows with shutters for the villa. Jerome’s deal with the local Catholic diocese, which owned the 1,000-year-old villa and the adjoining centuries-old church of San Martino a Scopeto, was that he could live, teach, and create there if he also remodeled the property for eventual use as a retirement home for diocesan priests. So the grunt construction and remodeling work was a big part of each week’s labor, and I learned a great deal about construction. I had been doing carpentry work for years under the tutelage of my father, but I had never done any electrical or tiling and I had little familiarity with cement. And so it made sense that Jerome started me with the windows.

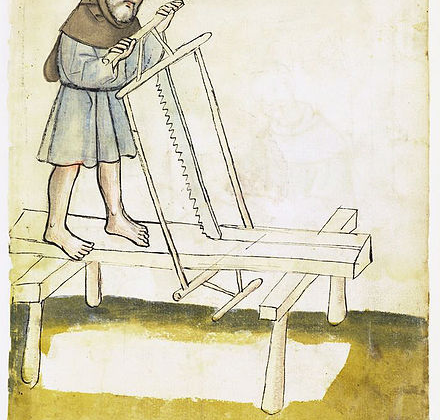

The problem was that Jerome, being appropriately poor for a Religious, liked to solve problems on the cheap. So instead of buying a tablesaw, he had simply inverted a SkilSaw and built a small table around it.

It worked brilliantly, except when you had to rip sixteen-foot planks in half without any supports on either end and without a safety guard over the blade. Which was exactly what I was doing when I came within a couple of millimeters of slicing my wrist open on it one afternoon.

“Jerome!” I said. “We have to get a guard for this tablesaw! I just almost sliced my wrist open!”

“Well, were you standing to the side of the blade?” he replied calmly.

“I couldn’t stand to the side. I had to use my hands to control the unsupported halves of the board.”

“Well, just be careful,” he said. “That’s all that’s needed. We don’t really need a guard.”

I paused for a moment as my stubbornness welled up within me.

“Brother Jerome, I will not use that tablesaw again without a guard.”

Jerome paused for a moment as his stubbornness welled up within him.

“Well, then, you will use a handsaw.”

And so I used a handsaw for the rest of the summer.

Things went on more or less this way for the rest of our months together. He assigned me to work on wiring the dank, dark wine cellar alone on the pitch blackness for days on end; he said later he thought I was enjoying it, but at the time it felt to me like an assigned penance. He once mistakenly told me the electricity was off when it was not, and when I went to connect to wires, I got a significant (though not dangerous) shock. And one day, when I was having an asthma attack on the side of the road after trying to bike up a too-steep hill, he wouldn’t drive down in the van to get me (and in the end, I was okay).

And yet…Jerome also took me to Carrara to see the quarry when there was no good reason to do so except that I might learn something and enjoy the trip. And although he usually refused to do any of the cooking, one day he surprised us all with bacon and eggs. He took us on drives through the countryside and introduced me to countless fascinating people, both Italians and others. He gave us weekends off to go to Florence, Rome, or Ravenna. He taught me to make wire-and-bead rosaries and gave me the opportunity to spend hours on end alone in the Medieval church, breathing in the musk and preparing my heart for conversion.

He taught me to turn wax into gold.

Brother Jerome died this past year, well into his eighties and after suffering from quite a bit of pain and a lack of mobility. I think sometimes of a wonderful memory of him and my dad standing next to each other at my wedding reception, both wearing eyeglasses and drinking wine, and both laughing with joy and happiness for the young woman whom they both loved in their own ways. And every year, like clockwork, he sent me a newsy and cheerful Christmas letter, always with little faces drawn at the bottom and funny little jokes sprinkled throughout. I am sure that more than once, he thought of me kindly, and prayed for me, too.

So Rest in Peace, Brother Jerome, and be assured that we remember you well. You truly drove me nuts. But you were also a good teacher.