Humor may be even more complicated than evil

Have you heard about the edgy new sit-com that’s in the works? It involves a cell of insurgents during the Iraq War. Part of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s terrorist organization in Iraq (you may recall Zarqawi for beheading American Nick Berg on video), these insurgents are bumbling, laughable incompetents. They are constantly being outwitted by Americans they’ve captured. There are endless hijinks involving malfunctioning IEDs. A fat terrorist has a secret love for the pizzas with pork sausage toppings he lets his captives order-in. A running gag involves the cell-leader’s inability to say Death to America! without sounding perfunctory and bored. Zarqawi’s lieutenants upbraid the cell for its lack of fearsomeness, but as much as the misfits try, they had better not depend on this wacky crew of mujahideens for any further advance!

OK, apart from the existence of Zarqawi, none of that is true.

But it once was. The popular 1960s sit-com Hogan’s Heroes did exactly that, only with Nazis.

Could Hogan’s Heroes get green-lit today? A lot of people are appalled that anyone once thought Nazis a fit subject for comedy, just as they’re appalled by Archie Bunker’s racism and Ralph Kramden shaking his fist at his wife and saying “To the moon, Alice, to the moon!” How is any of that funny?

It all betrays a horrifying insensitivity to minorities of all kinds and an irredeemably compromised conscience—as we might expect from people formed in America prior to the 1960s. Had they understood just how evil Nazis, racists, and sexists are, they would not have made fun of them.

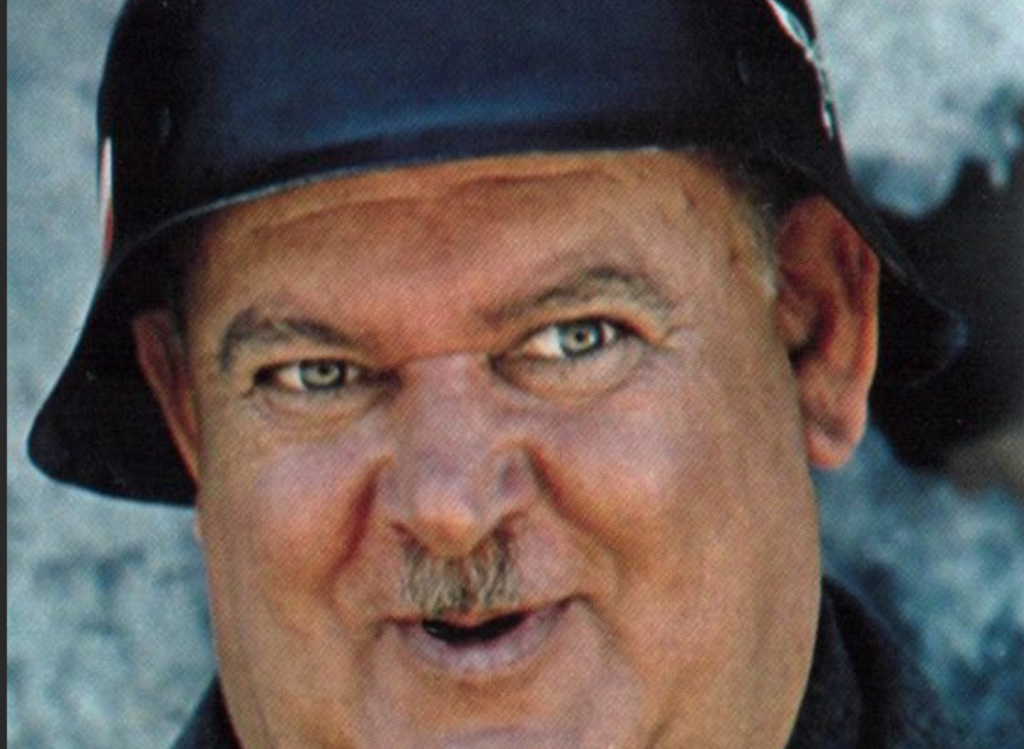

In the case of Hogan’s Heroes, though, it’s hard to believe the creators didn’t take their subject seriously. The two central Nazi characters—Colonel Klink and Sergeant Schultz—were played by German Jews who had fled the Nazis. Three other major characters were also played by Jews. Several had been held in concentration camps themselves, and some saw their families perish in the war—the parents of one at Treblinka. All five were World War II veterans.

Opinions differ on whether Nazism and other horrors can be fit subjects for humor, but I don’t believe the line is drawn between those who take evil seriously and those who don’t.

One of the lines does seem to be generational. If you were nine, as I was when Hogan’s Heroes premiered in 1965, you grew up with it. It was a beloved weekly moment of your childhood. Of course you’re not horrified, as so many of my slightly younger friends are. Not only did I watch it and laugh, I watched my father watch it and laugh.

My father, like all the forty-something fathers in the neighborhood, was a World War II veteran. He spent the first half of his twenties at war. His war was closer to him in 1965 than 9/11 is to us now.

Hogan’s Heroes wasn’t our only exposure to the war. It was everywhere in popular culture, portrayed as a heroic crusade. Sons grilled fathers for war stories at the dinner table. My father never brought it up himself, but when I asked, he answered, without self-pity, anger, or much in the way of soft-pedaling. When he told me about a kamikaze that hit his ship at Okinawa, taking out the bridge, officers, and numerous sailors, I asked if that hadn’t been sad. No, he said: Once they got the fire out, everyone was too busy scrambling for souvenirs. He got the flag and the sword but someone stole them. I was stunned: How could grown men—their own lives still in danger— be so petty and callous? (It may have been then that I began edging toward Calvinism.)

I can’t recall him ever making any judgments about such events. My father neither excused nor condemned other men, or himself. He didn’t even condemn his Japanese foes. Was he leaving space for me to draw my own lessons? Or was he too overwhelmed by it all to formulate a judgment?

We had other sources of information. One day in my elementary school library I discovered William Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, a far-too-detailed (especially when it came to Mengele’s “medical” experiments) 1000 page tome to be suitable for children. But check it out and read it I did; I learned more about Nazis than I wanted to know. It didn’t stop me from enjoying Hogan’s Heroes.

One thing the experience of World War II seems to have taught at least some of those who lived through it was complexity. The perpetrators of evil were also absurd, and the absurd is rich in comic potential. The “good guys” who saved the world from Nazism did evil themselves. And they knew it.

This sensibility resulted in no single moral precipitate. “All war is immoral anyway,” Paul Tibbets, the pilot of the Enola Gay, shrugged when asked if bombing Hiroshima was immoral. That could mean war is so wrong it should be abjured in toto. Or it could mean that since war is necessary, don’t get tripped up by the immorality of whatever needs to be done.

Is appreciating complexity a good thing? Some say it endows us with humility: It should teach you to examine your motives, your judgments of others, your plans for the reclamation of the world. Others say that itself is a problem: The last thing you should do when fighting evil is second guess yourself. President George W. Bush made it clear he was in the second camp when it came to the Iraq War. Questioning the purity or prudence of your commitment to “ending tyranny in our world” only distracts from the task.

Several years ago a roundtable discussion at the Society for U.S. Intellectual History blog addressed complexity head-on and found it wanting. Historian Keri Leigh Merrit saw a divide between older and younger historians regarding the question. “We believe,” she said, speaking for the younger, “that if we had been born fifty years ago or 500 years ago that we wouldn’t harm or abuse other human beings.” Farewell, tout comprendre, c’est tout pardonner.

When you’re a boy listening to your father’s war stories, you don’t assume that you would be a better man than he. What he could do wrong, you could do wrong. Watching My Lai unfold in the news, surrounded by guys who came back from Vietnam carrying some dark demons, you weren’t sure that in the same circumstances you might not be William Calley.

Later you carry that insight with you. One side-effect of a major war is that it has the potential to inject into a society a dose of Augustinian realism about human nature.

Robert Oppenheimer—the American physicist who developed the bomb that Tibbets dropped that killed tens of thousands of civilians, thus ending the war my father survived and later found ripe for laughing at—knew something about complexity: “We most of all should try to be experts in the worst about ourselves,” he advised. “We should not be astonished to find some evil there that we find so very readily abroad and in all others.” This is what “we most need: self-knowledge, courage, humor, and some charity. These are the great gifts that our tradition makes to us, to prepare us for how to live tomorrow.”

Is self-knowledge of that kind transferable from one generation to the next? Marine E. B. Sledge hints that it isn’t. In his memoir of the Pacific war, Sledge notes that it’s only through the personal experience of what one becomes in battle, when “the veneer of civilization” is stripped away to reveal the savage beneath, that anyone gets to know themselves at that depth. Those of us who have never had to face it should be grateful—to God, to history, to chance—for not having to. But we shouldn’t fail to respect it either. Those who have gained such knowledge did so at a bitter price, but they move through life with a clarity unavailable to the rest of us. We can get a sense of the things they’ve seen, but not of what the seeing itself did to them—or what was required to carry on.

John H. Haas teaches U.S. history at Bethel University in Indiana.

Image: CBS/Viacom