I took a little heat for my take on the Florida African American history controversy. Last month I wrote:

The standards were much better than I expected. If I was a high school teacher in Florida I could easily work with them. In fact, some of these standards for African American history are quite thorough. Of course historians will quibble about this or that, but these standards provide an adequate–even good– starting point as teachers prepare their lessons.

Today at The New York Times, Columbia University linguist John McWhorter writes:

But in general, if I had been handed this curriculum before the outcry, my impression would have been that it was going to offend the anti-woke crusaders of the right, not critics on the left. It is such a standard-issue coverage of what slavery was that it is, again, almost surprising that Ron DeSantis would want it to go out under his name. I would have processed that single “benefit” sentence as a tip of the hat to an idea, hardly uncommon among Black people thinking about our history, that even slaves exercised a degree of agency and human strength amid the horror of the condition imposed upon them.

I also wrote this on July 22nd:

Most of the attention, however, has focused on one standard. SS.68.AA.2.3 reads: “Examine the various duties and trades performed by slaves (e.g. agricultural work, painting, carpentry, tailoring, domestic service, blacksmithing, transportation). The standards then offer a “clarification” on this benchmark. It reads: “Instruction includes how slaves developed skills which, in some cases, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

Anyone who studies slavery in America knows that enslaved men and women learned skills during slavery. They were also sold based on these skills. And many of them used these skills when they became free.

Let’s talk again about the facts of history here. The enslaved learned skills during slavery. They used these skills in their lives as freedmen and freewomen after the passing of the 13th Amendment.

But let’s not deny the fact that the framing of this standard is political. The use of the word “benefited” is morally problematic, if not overtly racist. Here is McWhorter again:

The plan was reviled for a passage it contained directing that “Instruction includes how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

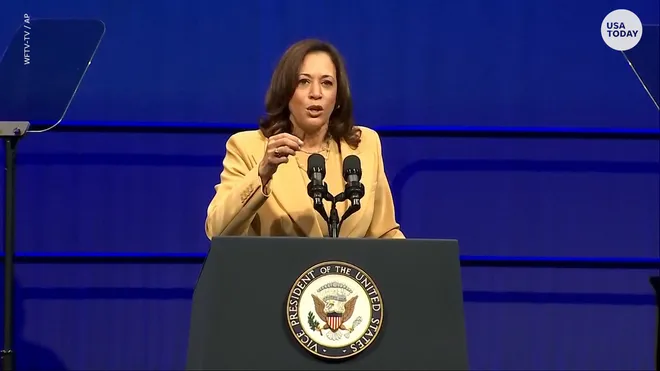

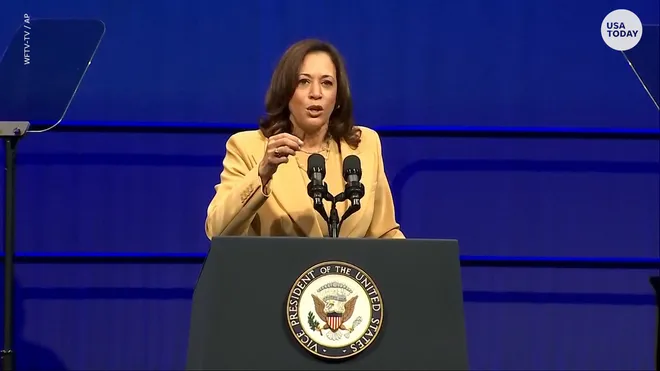

The response was swift. Most prominently, Vice President Kamala Harris, in a talk to a traditionally Black sorority, said that the work group had “decided middle school students will be taught that enslaved people benefited from slavery” and that “they insult us in an attempt to gaslight us, and we will not stand for it.” Nor did criticism come solely from the left: the Black G.O.P. representatives Byron Donalds and John James, as well as Senator Tim Scott, also decried the implication that slavery was somehow good for Black people.

True to form, DeSantis simply waved the criticism away. Cynical, dismissive and ungentlemanly, DeSantis neither compels nor impresses me overall. I revile the book banning and the antagonism toward changing conceptions of gender identity that he stands for. His peremptory response to a question about the passage was sadly typical: “They’re probably going to show that some of the folks that eventually parlayed, you know, being a blacksmith into doing things later in life.” This is a sensitive issue. A larger figure would at least have addressed it with more thought and consideration.

The passage is certainly ungainly, and it bears editing at least, and probably deletion. My colleague Jamelle Bouie has usefully outlined that any real evidence of slaves “benefiting” from their work skills took place after emancipation, not during it. Moreover, the idea of any kind of benefit gained amid the pitiless horror of slavery is highly strained, creative and almost certainly unnecessary in a curriculum instructing students about this stain on the nation’s past.

There are a few other problematic parts of the standards as well, but in the end I think McWhorter is right here:

…from the tone of coverage of this passage, one might suppose that it was a central plank in the curriculum. Instead, it was but one passage amid hundreds of others, which constitute an almost exhaustive coverage of the gruesomeness of slavery in the United States. Taken together, they are such an informed recitation of our racist past that it is almost surprising DeSantis would approve them.

Many consider it unwise to condemn someone’s character permanently on the basis of one clumsy tweet. Likewise, judging this curriculum on the basis of a single sentence — a great many of the other passages consist of small paragraphs — means not seeing it whole. Yes, it is a flaw. But does it justify assailing the work group’s efforts as a sinister attempt at “gaslighting” students?

So here’s the question: Does the “benefited” line (and a few others) mean we must reject all the Florida African American history standards? I think different historians will answer this question differently. But when taken as a whole, and viewed in the context of the last fifty years, these standards reveal the profound influence that scholarship in African American history has had on the curriculum.

I would advocate keeping the document and rewriting a few parts of it. In the end, I don’t know how an elementary school or high school student could come away from a series of classroom lessons guided by these standards and not have a solid grasp of the evils of slavery in the United States. Again, read them for yourself.

But what about the teachers who must use these standards?

The coverage of these standards seem to suggest that history teachers are simply machines who robotically deliver, word for word, what is written in their state’s standards. (I am exxagerating of course). Most of the critics of these standards have no idea what happens in an American history classroom–and that includes Kamala Harris.

I can’t speak for other colleges and universities that train history teachers, but I have been teaching history teachers for more than twenty years. My future and current teachers know what to do with these standards. They can see through the politics. The best teachers will use these standards to talk about the difference between history and politics. They will treat the standards themselves as a primary document. They might ask: “Why would these standards say that slaves ‘benefited’ from history’?” Or: “how did the context of Florida and national politics shape the writing of these standards or the selection of the drafting committee?” These teachers might talk with their students about the resilience and agency of the enslaved AND the way in which politics and the media use the past to promote this or that agenda. They might try to get inside the head of William Allen, a Black conservative scholar who apparently wrote the “benefits” standard, and wonder why the descendant of enslaved men and women might want to include such a line. They might also think about Kamala Harris’s outrage as a woman of color or as a surrogate for Joe Biden in the 2024 presidential election.

The standards are not perfect. But they are usable. I hope teachers will rise above the cultural war politics and use this moment as yet another opportunity to teach students how to think historically about the past.

Curious about what kind of heat you generated. I, too have examined the standards and find much to commend them along with the resources available at CPALMS here in Florida to help students explore the issues. Like you and others, I probably would have contexualized the meaning of “benefitted.” Part of the real problem is the tendency to view the African-American experience as nothing but victimization. Any competent educator will ask how Black communities demonstrated exceptional courage and creativity in rising above their circumstances. I think of the Clubwomen’s motto “Lifting as We Climb.” I also believe that one cannot fully appreciate “Lift Every Voice and SIng” without recognizing that hope is a major theme of this anthem. In Holocaust Studies, focusing purely on the victimization of the Jews under the Third Reich is one-dimensional. I spend a lot of time examining how victims of racism manage to build solid families, thriving economies, and a strong sense of personal dignity under nightmarish conditions. There are many ways beyond violence to resist one’s conditions.

I appreciate your discussion about how–or even whether–standards are actually taught in schools. I’ve visited countless classrooms in multiple states. Those visits confirm what research demonstrates: Most teachers seldom, if ever, consult these exhaustive, often obtuse standards documents in creating curriculum or planning their daily lessons. The actual, taught curriculum for the same course, within the same school or district, varies dramatically from teacher to teacher. This little-known fact provides important context for our debates about educational standards.

Mike Schmoker

Author, Results Now 2.0 (ASCD, 2023)