In 1982 The Gap Band had a hit record with the song “You Dropped a Bomb on Me.” That song was a rather unconventional take on the love song. I guess if someone drops a love bomb on you that’s a good thing.

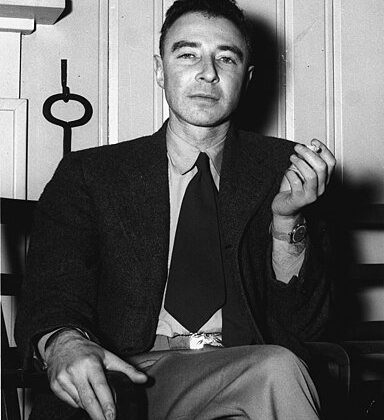

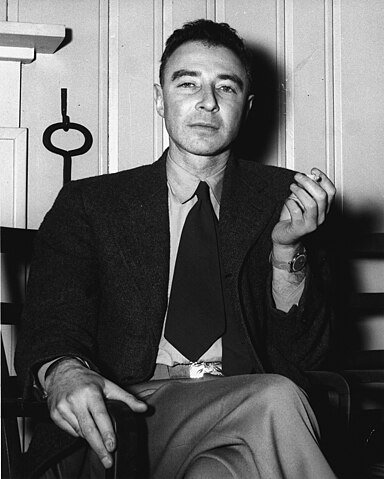

I don’t know if the Gap Band’s bomb was nuclear or not, but the release of the film “Oppenheimer,” the story of J. Robert Oppenheimer and the American development of the nuclear bomb in the 1940s, has once again opened the question of the justice behind the American dropping of two nuclear bombs on Japan to bring World War Two to a conclusion. Was this an act of naked cruelty, killing tens of thousands of Japanese civilians in a desperate attempt to finish the war quickly? Or was this a tragic but necessary operation brought about by Japanese intransigence and, given the likely brutal outcome of a conventional invasion of Japan, one that may have saved lives, especially those of American servicemen?

First, let me dismiss the pacifist objection that all war is unjust. I don’t mean to say that it is not a serious position, but this is one that is held by a small minority. Thus it is not a typical objection to the U.S. bombing of Japan. Almost all agree that given the ruthless nature of the German and Japanese regimes and the naked aggression in which they had engaged, some sort of violent response was justified.

So let us assume that the basic war aims of the United States were just. In just-war theory, when it comes to the actual prosecution of war, there are two key principles: discrimination and double-effect. Discrimination in this context simply means that a military must make a distinction—it must discriminate, between combatants and non-combatants. That’s not as easy as it may seem at first glance, but let us stipulate that civilians are typically seen as non-combatants.

That doesn’t mean you can never attack civilians, which brings us to double-effect. Some targets that are normally thought of as legitimate military targets, if attacked carry the likelihood of civilian death. Munitions factories or power plants are examples. They contribute mightily to the war effort but are largely staffed by civilians, i.e., non-combatants. The bombing of such a facility is said to have two effects—a double-effect—namely the destroying of a legitimate military target and the killing of civilians. Just war theorists usually argue that such an attack is just if the intention is to destroy the military target. In other words, one cannot target civilians qua civilians.

Both of these principles—discrimination and double-effect—are implicated in the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. The problem with nuclear weapons, and why some argue that to use them is never just, is that they are by nature indiscriminate. The devastation is so wide that it is a kind of weapon that by its nature violates the principle that one must make distinctions between combatants and non-combatants. It certainly renders such discrimination very difficult.

Further, the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings were quite purposefully of population centers. While Hiroshima contained Japanese military assets (for example 2nd Army headquarters), clearly the intent of dropping the bombs on Japan was to create mass civilian suffering to push the Japanese government to surrender. Michael Walzer argues that American insistence on unconditional surrender was unnecessary, thus any argument of military or strategic necessity fails. By August 1945, Japan was beaten. It was only a matter of time. Why go to such horrific measures to end the war when one could either use more discriminant conventional military methods and/or simply negotiate rather than impose surrender conditions? From Walzer’s view, America in August, 1945 was not in a “supreme emergency” and therefore could not justly argue for an exception to what Walzer calls “the war convention.” America should have obeyed the rules of discrimination and double-effect. The bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was wrong.

Those who counter this view typically point to three factors that might justify the dropping of “the bomb.” First, they argue that Japan was essentially one large armed camp. The whole island had been militarized. Any attack on the Japanese mainland was going to implicate civilians. Bombing defenders also point out, accurately it seems, that any conventional attack would have caused massive casualties, including civilians. Some argue that the bombs may have caused less civilian death than a conventional invasion would have. We’ll never know, but it is likely that the civilian death toll would have been high. It is near certain that military death tolls would have been catastrophic. Finally, given the nature of the Japanese regime, a negotiated surrender was both unwise and quite likely impossible. Unconditional surrender was the only realistic option. For all these reasons, dropping the bombs was just.

I tend to side with Walzer and the view that the dropping of the bombs was wrong. You can’t target civilians to save military lives. As Walzer points out, soldiers signed up for death (yes, including the conscripts) but civilians did not. While war inevitably contains all sorts of absurdities (noted in literature by the likes of Evelyn Waugh and Kurt Vonnegut), it does seem to turn the whole idea of war on its head to say we are going to attack the civilians to spare our military.

At the same time, when I put myself in the shoes of Harry Truman, I have a hard time condemning him. Those who call the bombings unjust should refrain from moral preening and show a hint of humility. The world had been at war for six-plus years, America for nearly four. The devastation had been ruinous. America alone had casualties of about 400,000 dead and another 600,000 wounded. Truman saw a way to end the war without months of gut-wrenching death and destruction, slogging block by block, city by city. One can say Truman made the wrong choice—and I do—but I will not be the one to judge him. Let us just hope and pray that no world leader ever faces a similar choice.