This is Part I of a two-part post. Stay tuned for Part II coming next week, which will focus more on Colleen’s on-going research on enslaved girls and manumission in Jamaica.

As you are getting ready for a new academic year, what are your favorite classes to teach, and why?

Hands down, one of my favorite classes is my American Foodways class. Food has played a consistent yet complicated role in the shaping of national histories, social relations, personal experiences, and cultures, and this class explores how by examining the various intersections between food and culture across the American landscape from the pre-Columbian period through the present day.

The class counts towards our Nutrition Minor, our Public History Program, our Women’s Studies Minor, and our Africana Studies Minor, and it has grown into an interdisciplinary smorgasbord (see what I did there?) with a little something for everyone. The class is still a history class at its core, but having these interdisciplinary student perspectives gives each semester its own personality, challenging me to think outside of the box historically and pedagogically each time I teach it.

The class is also a deeply personal class for many students who spend the semester considering how their ancestral, familial, and community foodways are maintained, reinvented, and changed with each generation. By the end of the semester, students leave the class seeing food as something more than “what I ate today,” and I always learn something new each semester.

Then there is “The Contest.”

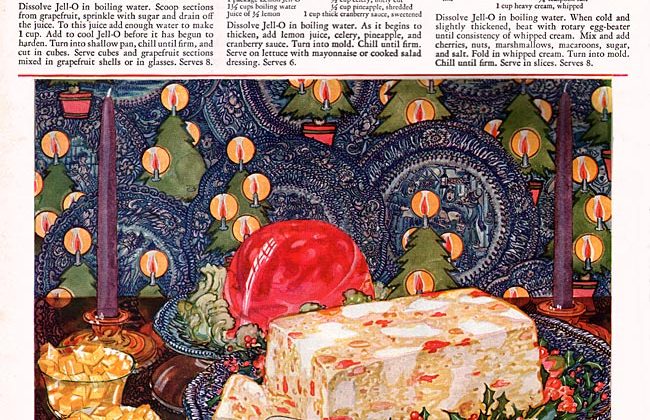

The 1950s were not kind to food, and one particular article on Perfection Salad started quite the gross-out competition in the discussion forums. Google “Perfection Salad” if you dare, but don’t say I didn’t warn you.

This was Fall 2020, just a few months after quarantine, and we were completely online and in desperate need of comic relief. That semester, as we began our unit on post-war foodways, my students naturally started posting photos of 1950s food, which quickly evolved into photos of gelatin salads, with each one worse than the last.

One was a disgusting mix of lime gelatin and tuna salad shaped like a fish with pimento stuffed olives for eyes that seemed to follow you around. Another was an elaborate mold of gelatinous goo with hotdogs and pineapple decorated with what I hope was mashed potatoes piped into the center.

The students were determined to outdo each other with each post, so I rolled with it and the “If 2020 Was a Jell-O Salad” Contest was born! Students voted for their Top 3 Abominations, and the winner with the most votes received extra credit. Word spread far and wide, and The Contest has become a major selling point for the class. This Fall I will cautiously preside over the 4th Annual contest Jell-No Contest.

My second favorite class is my Golden Age of Piracy class. I have taught this class as a grad readings class, an interdisciplinary class for the Honors College, a first year interdisciplinary seminar for Freshmen, and as an undergraduate history class. It just keeps getting better each time I teach it.

It all started with my graduate Historiography Seminar and Marcus Rediker’s Villains of All Nations. While some of my colleagues go with Eugene Genovese’s Roll Jordan Roll when discussing the Marxist historians, I decided to shift to a more nuanced (and significantly shorter) take. I also saw an added opportunity to apply Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities, another work I very much admire.My students loved Rediker’s book, and we had one of the best conversations of the semester the evening we discussed it. For weeks afterwards, they asked if I would consider offering a class on piracy in the future so I made it happen. I mean, twist my arm, right?

While the grad Piracy class spent the semester reading everything we could find on pirates, we also had a movie night once a month and watched Errol Flynn as Captain Blood, Johnny Depp’s Captain Jack Sparrow, Robin Williams’ adult Peter Pan in Hook, and Lionel Barrymore as Billy Bones in Treasure Island. Students invited friends and brought dates, a few of my colleagues joined us, and one colleague’s son came as well. When I began offering this class for undergrads, I decided to add some creative components to each unit. Now we spend the semester designing flags, crafting Codes of Conduct, writing urban legends, keeping a Captain’s Log, and participating in a semester-long treasure hunt. I love this class so much, and we have a lot of fun.

If someone wanted to dig more into the history of piracy, in particular, what would you recommend?

Haha. Well, how much time do you have? Seriously though, let’s start with books. There have been some very good books written about the Golden Age of Piracy, and I would start with Rediker’s Villains of All Nations. He does an excellent job providing a social history of piracy, and it is a great read. You come away from it feeling like you have a firm understanding of who these men are and what brings them to this occupation.

I also love Peter T. Leeson’s The Invisible Hook, which is an economic study of piracy written for non-economists. It works well with Rediker’s social history by digging deeper into the inner workings of the ships and the democratic practices that were utilized to maximize profits.

Laura Sook Duncombe’s work focuses on women who worked and interacted with piracy in various capacities. I like her work because what is out there on women tends to focus mostly on Anne Bonney and Mary Read, and otherwise treats women merely as a footnote to the history of piracy. Duncombe expands the focus to bring in more women pirates, but also considers how history has marginalized their stories and removed their agency from the narrative. She also has an excellent examination of Elizabeth I’s complicated relationship with piracy that really sheds light on the changing nature of empire during this period. From there, you can branch off to themed articles that focus on anything from specific pirates to pirates of color like Black Caeser to homosexuality aboard ships to piracy’s relationship with the trans-Atlantic slave trade. I could keep going, but that will get you started.

I’m sure our readers really want to know: just how authentic is the “Pirates of the Caribbean” franchise anyway, historically speaking?

Well, this is Disney we are talking about, right? I think the first movie hits on nearly every stereotype out there, and the ones that follow in the franchise add even more.

Then there is the sanitized characterization of the Caribbean itself. The region was a cesspool of violence, hedonism, disease, and death, and Disney doesn’t touch upon the ways Europe not only exploited the land with sugar and coffee cultivation. Then there is the history of the millions of people who were trafficked and enslaved there as part of the African Diaspora and the British penal system. Once you get over that and embrace the campiness and Disneyfication of anything close to reality and decide to enjoy yourself and the movies for what they are, then you can have a good time.

That said, you can see a lot of metaphor in the movies that corresponds with what we know as historians. There was certainly superstition aboard ship and in pirate enclaves where crews camped out, and Davy Jones, The Flying Dutchman, krakens, mermaids, and Calypso have established mythologies that many took very seriously.

We don’t have skeleton crews manning ships in the moonlight, but death was an ever- present concern anywhere in the Caribbean during this period (and in the rest of the world too, I should say) and many a flag expressed that imagery. I appreciated the spunky governor’s daughter who represented women’s growing frustration with society’s expectations and I quite imagine Elizabeth Swan presiding over an enlightened salon had she lived in another time. Her role as a pirate herself is representative of the nameless women who never seem to emerge from Anne Bonney’s shadow.

At World’s End, the third installment in the franchise, also acknowledged other pirates in other cultures, as well as the historical confederation of pirates that existed within this society. The Royal Navy’s frustration with piracy is well documented, and Tom Hollander’s place as the ruthless head of the East India Company was a great representation of how detached these administrators were and how rampant the corruption ran.

So, if you can stop wondering why the rum is gone, there’s something to be said for these movies—what they subconsciously do well, and what they do to spark interest in historical topics. Well, that is until Hollywood begins using them as a cash cow and they get so ridiculous that they become unbearable to watch.