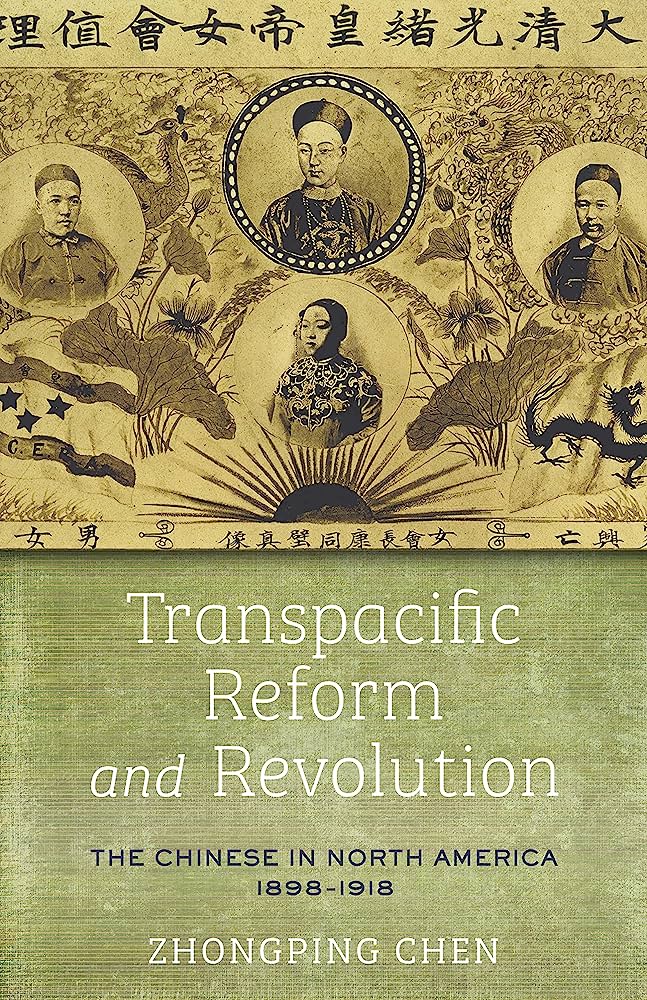

Zhongping Chen is Professor of History at the University of Victoria. This interview is based on his new book, Transpacific Reform and Revolution: The Chinese in North America, 1898-1918 (Stanford University Press, 2023).

JF: What led you to write Transpacific Reform and Revolution?

ZC: I first became interested in the subject of the book after I arrived in Honolulu as a doctoral student in 1990 because Sun Yat-sen, the “father of Republican China,” started the Republican Revolution from there in 1894. I also became interested in the subject after I began to teach at the University of Victoria in 2002 because Kang Youwei, a major agitator for the first but failed political reform in modern China in 1898, restarted his constitutional reform among the worldwide Chinese communities from this Canadian city in 1899, although his movement declined one decade later. What really piqued my interest is my primary research on the political assassination of Tang Hualong, an important statesman of early Republican China, in Victoria in 1918. Later, I found that this assassination in Victoria was linked to another political murder of a highly influential Chinese journalist in San Francisco in 1915. I was also surprised to find that the first Chinese women’s political organization actually started in Victoria in 1903, then spread to nearly a dozen Canadian and American cities, including Honolulu, by 1905. Moreover, Sun Yat-sen won support from the Chinese Freemasons in Victoria in early 1911 and then in other Canadian and American cities, including San Francisco, which helped make him the first provisional president of Republican China in 1912. All of these discoveries led me to write the book that covers the political history of modern China, Chinese Americans, Chinese Canadians, and the Chinese communities in the Pacific Rim between 1898 and 1918.

JF: In 2 sentences, what is the argument of Transpacific Reform and Revolution?

ZC: Reform and revolution in North American Chinatowns jointly led to a network revolution in the transpacific Chinese diaspora because both movements fundamentally transformed the relations among migrant participants and their interaction with the hostland culture, with homeland politics, and with their co-ethnic communities across the Pacific Rim from 1898 to 1918. Specifically speaking, Chinese migrant participants in both movements broke through racist barriers to identify themselves with the US and Canadian constitutionalism, republicanism, and other political cultures, turned themselves from overseas subjects and sojourners of imperial China into promoters and protectors of Western-style constitutional monarchy or republic in the homeland, and achieved unprecedented ethnic interconnectivity in spite of reform-revolution competition.

JF: Why do we need to read Transpacific Reform and Revolution?

ZC: This book reveals the long-neglected history of Chinese American and Chinese Canadian politics, especially their interactions with the Western political culture beyond anti-racism struggles, their interrelations beyond reform-revolution competition, and their influence on modern China and the transpacific Chinese diaspora. Additionally, this book uncovers previously untold stories of feminist politics, secret societies, and political assassinations that occurred in American and Canadian Chinatowns between 1898 and 1918.

JF: Why and when did you become an American historian?

ZC: I had already been an established scholar in Chinese history before I expanded my research interest into American history at the University of Hawai‘i in the 1990s. The doctoral program at the University of Hawai‘i provided me with further training in local Chinese history and global history, and I began to start historical research on American Chinatowns from then on. Certainly, I later also became interested in Canadian history, but my research always tries to link the different local and nation-state histories with a transpacific or global approach.

JF: What is your next project?

ZC: I have just finished a new book manuscript, “The Transpacific Chinese Diaspora in Canada: From Origins to Rise and Reform, 1788−1898,” and my next project is federally funded research on late imperial China and the Little Ice Age (1400−1900), in which climatic change affected most of the world.

JF: Thanks, Zhongping!