A mid-20th century novel reaches easily across the decades

Forbidden Notebook by Alba de Céspedes. Astra House, 2023. 288 pp., $26.00

Alba de Céspedes’s 1952 novel Forbidden Notebook traces the disintegration of a woman’s internal life as she begins to keep a secret diary. A new generation now gets the chance to discover this book, translated from Italian to English for the first time this year. What many readers, including me, are finding is that Forbidden Notebook remains remarkably resonant seventy-one years after its original publication.

Perhaps the most obvious relevance for modern readers lies in the financial anxieties of Valeria, the novel’s protagonist and narrator. Valeria, who lives with her husband and children in Rome as the city recovers from World War II, mentions money almost constantly. While her parents were well-off, Valeria and her husband, Michele, both work full-time and can still barely afford the small apartment they share with their two almost-adult children. The story’s dramas and tensions all take place against this backdrop of extreme financial instability—Valeria falls in love with her boss; her husband launches a failed attempt at a screenwriting career. For American readers, especially millennials like me, this situation is all too familiar: We are worse off financially than the previous generation and unable to work our way into a better situation. De Céspedes describes the nonstop worry and angst of this anxiety over finances with a level of realism and care that bridges the years between Valeria and today’s readers.

For women readers, Valeria’s descriptions of her day-to-day life may hit even harder, as she struggles with the unequal division of labor in her home. Despite working as many hours in the office as her husband, Valeria is entirely responsible for domestic labor; Michele spends much of his time reading the paper and listening to records. At the book’s beginning Valeria writes heartbreakingly, “I’m always tired and no one believes me.” On the one occasion that she leaves town to visit a friend, she finds that “endless chores had accumulated during my brief vacation.” After months of writing in her notebook, though, Valeria begins to wonder if things could be different. “Often, when faced with men’s bad moods,” she writes, “I wonder what they would do if instead of only their office job they had, like every woman, so many different problems to confront and solve.” Unfortunately, gender imbalances in domestic labor remain almost unchanged since the novel’s publication.

These tensions also affect Valeria’s relationship with her children. Valeria’s son, Ricardo, reads almost like a predecessor for today’s incels and other modern misogynists. Many of Ricardo’s sentiments could easily belong on an incel message board, as he utters lines like, “Girls today no longer feel they have these responsibilities, they have no desire to make any sacrifice, they value only money.” Or: “Men have nothing to say to women, because they have no interests in common.” Although Valeria treats her son with obvious and undeserved favoritism over her daughter Mirella, she expresses sentiments about him that recall criticisms of today’s incel misogynists: “He seems to want to discover everywhere an evil that’s not there, a scam he expects from life and would like to thwart by force or cunning.”

Despite these powerful connections between the past and the present, the reality remains that this novel is almost three-quarters of a century old, which makes reviewing it a unique experience. It feels that with time potential criticisms of a book like this might fade away. What could be seen as rough edges in a contemporary novel—the book’s maddeningly slow pace at times, for example, or the tendency of Mirella to speak in lectures that border on manifestos—feel almost sanded away by time. Still, other moments serve to remind us just how far apart we are now from Valeria. The family feels poor because they aren’t able to hire a maid, for example. This is an extravagance that is both out of reach for most people today and arguably relies on an exploited and underpaid working class. Despite these potential shortcomings, it is impossible not to be impressed by this important and beautifully translated book, as well as by de Céspedes’s masterful handling of so many complex interpersonal and existential subjects.

One standout among these topics for me is the almost cold and always impactful dissection of relationships between mothers and daughters. De Céspedes’s descriptions of motherhood are by turns tender and brutally honest. “Sometimes we’re united in absolute intimacy, when we forget we’re mother and daughter,” Valeria writes. Then, later: “Sometimes I think that if she weren’t my daughter, it would be hard for me to love her.”

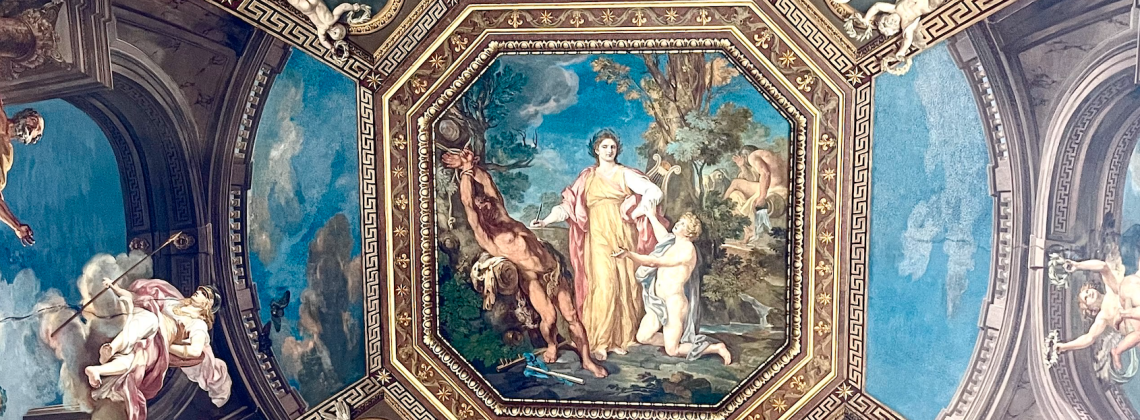

Perhaps I felt this exploration especially deeply because I happened to read Forbidden Notebook while in Valeria’s hometown of Rome with my own mother. Having never been to Europe before, we had decided to embark on a “now or never” trip together, and so I read many of Valeria’s words in a small hotel room on Via dei Chiavari while my mother snoozed in the room’s other twin bed.

While Valeria was born three generations before my own mother, many of Valeria’s lines could have come from my mother’s mouth. When Mirella gets a new job at a lawyer’s office, for example, Valeria says: “I asserted that I wanted to speak to this lawyer, ‘at least to let him know that you’re not alone in the world.’” My mother has said the same thing countless times, sharing Valeria’s desire to let the world know that her daughters are not alone.

As I read Valeria’s story in Valeria’s city, I couldn’t help but feel a kinship between the women of this story, my mother, and myself. Like Valeria and Mirella, we are both women who work. Today, though, our working isn’t so much an indication that we’ve fallen from financial grace as it is an expectation for survival. Yet, we were lucky enough to save our earnings for this trip together. Like Valeria, my mother and I are both writers, taking refuge in the written word at the end of our workdays, and at times feeling that eternal writers’ sentiment that Valeria describes: “What anguish. I would be better off to stop writing.” Finally, like Valeria, my mother has made untold sacrifices for her children.

I found myself wondering how much my mother has sacrificed for me, and if it was worth it. I wondered as we had maritozzi and espresso for breakfast. I wondered as we squelched in rainboots over Rome’s ancient cobblestones. I wondered as we craned our necks in breathtaking churches and as we walked past the same “carts overflowing with vegetables, the windows of the food shops, the dazzling lights, the voices” that Valeria describes. Was this trip, this chance for my mother to visit the land of her ancestors with her own daughter, perhaps making up for the sacrifice of motherhood? Could just one week do that? Could a lifetime?

As Valeria writes, “Sometimes children almost feel ashamed of having been born, of needing to eat, to have clothes.” I wonder if Valeria’s children ever tried to similarly repay her once they reached my age. As readers, we never find out. The book ends with Valeria’s abandonment of the notebook; she writes that she is ready to subjugate herself to her family’s needs once more. To me, though, this didn’t feel like the end of Valeria’s story. I have a feeling she didn’t completely let go of her desire for self-actualization, and I hope that her daughter didn’t either.

Sunny Rosen is an MFA candidate in fiction at LSU, a copywriter and publicist for LSU Press and The Southern Review, and fiction editor for New Delta Review. Her work has appeared in outlets like Taco Bell Quarterly and The Huffington Post. Originally from Newark, Delaware, she currently lives in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and you can find her on Twitter @sunnyraeanna

Images by the author from her recent trip to Rome with her mother