A young man, bored with his life and searching for excitement, takes a road trip. He gets much more excitement, however, than he had bargained for, when his new girlfriend accidentally turns him into a donkey by smearing the wrong lotion on his body. Oops. Don’t you hate it when that happens? Unable to get the cure for regaining his human form (fresh roses, administered internally) right away, he is stuck in his new guise for a while, taking the ultimate road trip in the process. It turns out to be much less glamorous than he had expected.

This is, at its most basic level, the plot of Apuleius’ Metamorphoses or The Golden Ass, the only Roman novel in Latin to survive in its entirety. Incidentally, thanks to Egyptian papyri, plenty of novels from the Roman Empire survive that were written in Greek, but that’s a story for another day. In honor of summer road trips, though, I contend that The Golden Ass really is the best road trip novel you’ve never read.

The protagonist and narrator, Lucius-turned-donkey-by-accident is not, mind you, a willing participant in said road trip. He is, rather, repeatedly stolen, kidnapped, sold, and traded in his donkey form. His observations show the underbelly of the Roman Empire during the period that otherwise some (*cough* Edward Gibbon) have considered “the happiest age of mankind.”

In fact, we might justifiably push the question further: to what extent do the protagonist’s experiences reflect the underbelly of the mighty empire, as opposed to the normal state of affairs for all but the highest echelon of Romans? Historians contend that this novel is one of the best primary sources that we have for ordinary life in the periphery of the empire, as it shows the brutality and discomforts of that life quite openly and unflinchingly. The flinching is left to the first-time reader, perhaps. Things get quite shocking at times.

Two years ago, Peter Singer, an ethicist best known perhaps for his defense of animal lives over human ones, produced (with the aid of a translator, of course) a new abridged edition of this novel, throwing out all the side stories and anecdotes that (he contended) unnecessarily cluttered the story. More interesting to focus just on the main story, he insisted.

In walking through his thought process on this project, Singer explained that his interest in the novel to begin with was from an animals liberation perspective—here is an entire novel with an animal protagonist!—but he was doubtful as to its literary merits. He made this assessment based on his own previous lack of familiarity with the work: “The obvious explanation for the absence of The Golden Ass from the works with which I was familiar was that, despite Zimler’s praise of its literary qualities, it can’t really be a good work of literature.”

I suppose you too could coolly go around stating that any work of literature that you haven’t heard of before can’t be any good. But maybe we can do better. Believe it or not, while only a tiny fraction of Greek and Roman literature made it out of antiquity, the surviving literature includes some really good texts that you have likely never heard of, or never read. They just don’t make it into many reading lists, other than those required for Classics PhD students.

The vast majority of “Great Books” curricula or reading lists I have seen do not include much or any Greek tragedy, Greek and Roman comedy, or (indeed) ancient novels. They also eschew most ancient historical writing (except, maybe brief excerpts from Herodotus, Thucydides, and Livy), ancient manuals and handbooks, ancient letters, sermons, and travel literature.

To be clear, I am not saying this to take a jab at friends in the Great Books circles. There is much wisdom to the selection of the authors and texts that do make it habitually into every list (e.g., Homer, Plato, Vergil). The reality is that there are a lot of good texts from ANY time period, including the modern world, that most of us have never heard of and certainly have not read. It is the curse—or blessing—of being finite creatures with limited time and ability.

Any one of us can only read so much in a lifetime, and we have to come to terms with this finitude that is a defining aspect of our humanity. This is in no way a reflection on the quality of any of the books we haven’t read. Although, a Homerist friend recently learned to his chagrin that Goodreads ranks his beloved Odyssey a mere 3.8, significantly lower than Click Clack Moo, an epic tale of a humbler variety, albeit one that Singer would likely appreciate for its distinct tones in favor of animal liberation.

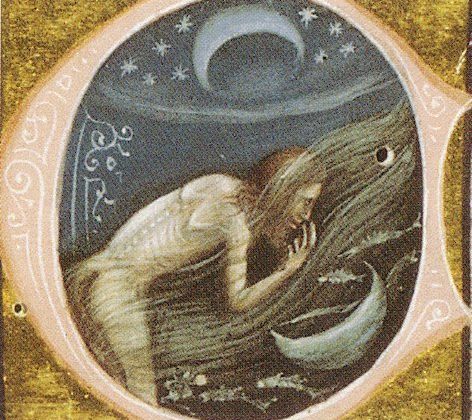

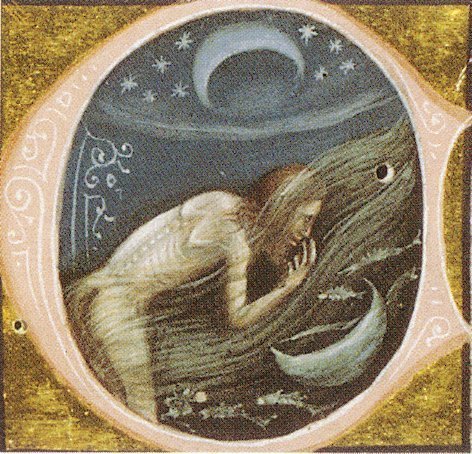

I don’t want to give away too much, at any rate, about The Golden Ass—a title, incidentally, that Augustine bestowed on this novel. Believe me, the ending will shock you and is worth the wait. I am not spoiling it for you here, although I will caution that the novel contains some violence and sexually explicit material that is inappropriate for precollegiate readers. But I do want to mention one other reader, in addition to Augustine, who found himself enthralled and deeply influenced by Apuleius’ novel. Specifically, this reader used one of the side stories, which Peter Singer had found so annoying in this novel, as the inspiration for one of his own novels. I am speaking here of none other than C.S. Lewis and his stunning novel Till We Have Faces.

Lewis based his novel on the Cupid and Psyche episode in the middle of Apuleius’ novel, transforming it into a tale about the failures of the pagan gods, and the search for the one true God.

Based on a recommendation of an elderly friend, now gone for several years, I read Lewis’ Surprised by Joy shortly after my own conversation to Christianity at age thirty. For Lewis, immersed as he had been for all his life in the myths of pagan gods, his conversion transformed how he saw the ancient world, its myths, its literature. Till We Have Faces reflects this transformation in practice. This novel is a conversation, a response from Lewis to Apuleius. It is also a reply from a zealous convert, who found Christ in middle age—in medias res of his life, so to speak—to a lifelong pagan, who was clearly on a spiritual journey of his own.

The world Apuleius describes is cruel, vicious, careless. But Lewis shows the redemption of that world and its stories for the benefit of another world, one no less fallen—our own.