Clashing appropriations of an ancient symbol underscore the extent of our contemporary crisis

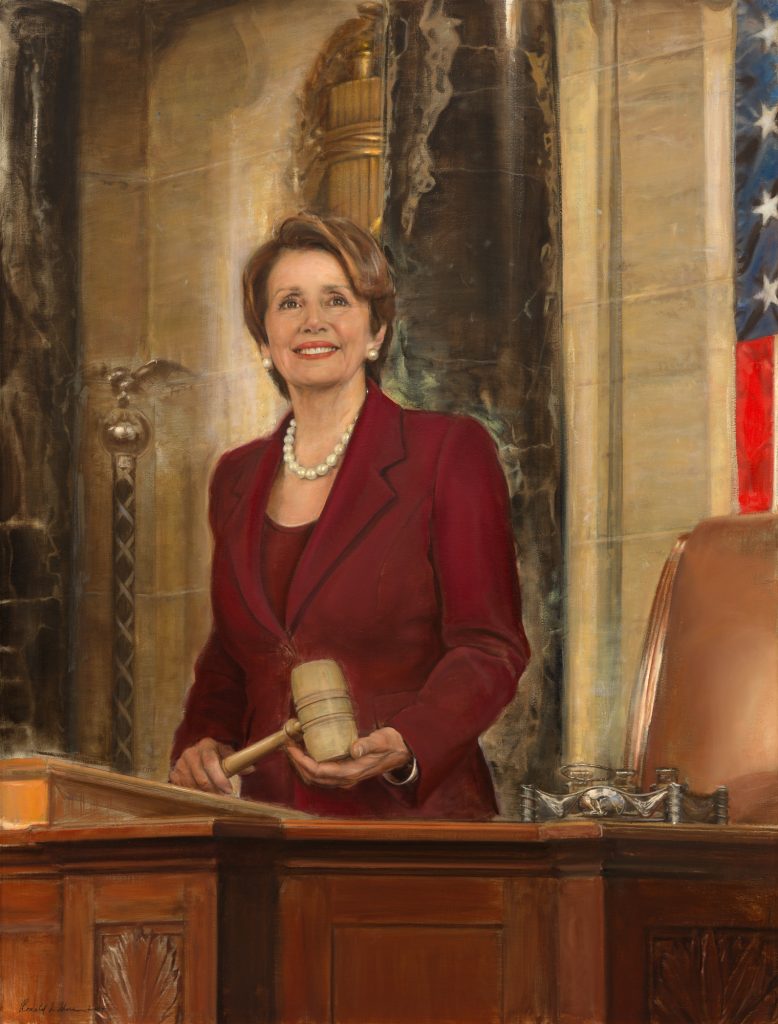

In 2014 Ron Sherr painted the official portrait of Nancy Pelosi as Speaker of the US House of Representatives, marking her service from 4 January 2007 to 3 January 2011 in that post, second in line to the presidency. Slated to join the long series of her (exclusively male) predecessors’ portraits on the walls of the Speaker’s Lobby, just outside the House chamber, the portrait remained in storage, unseen, until a mid-December 2022 celebration toward the end of Pelosi’s second term as Speaker. Sadly, Sherr died just a week before his painting was unveiled and installed.

Like other Speaker portraits, Sherr’s oil-on-canvas work is huge: more than five feet tall and a little more than four feet wide. The whole composition exudes authority. The angle is from the far right of the Republican side of the aisle, gazing up at the Democratic leader, as she stands on the Speaker’s Platform, gavel in hand, looking off at some distant point. Familiar features of the decorative “frontispiece” (1857, redesigned 1950) behind the rostrum amplify the Speaker’s status. The view gives us two of the four monumental black marble columns, the upper portion of one of the two large bronze Roman-style fasces in relief, and a snippet of the large United States flag long displayed behind the chair. The Mace is depicted close to Pelosi’s right and the fasces extend almost directly above her head. Against these points of reference, Sherr portrayed Pelosi on the platform as somewhat of a giant, rising at least two feet higher than any Speaker would in reality.

What caught my attention in Sherr’s portrait is the prominence of the fasces and the fasces-like Mace, rarely highlighted in images of the House. Perhaps a quick word of explanation is needed. In ancient Rome, the fasces were a bundle of wooden rods bound with a leather cord, in which an axe was placed—in essence, a mobile kit for corporal or capital punishment. For almost two millennia, Rome’s higher officials used attendants carrying this deadly device to mark their authority. Starting in the Renaissance we find revivals and reinterpretations of the fasces as a symbol, especially the spread of the notion that the bound sticks symbolized strength through unity.

It is this distinctly non-Roman aspect of the fasces that largely has informed its use in American public life. Soon after reaching its first quorum in 1789, the U.S. House of Representatives decided that its Sergeant at Arms should receive a Mace with a shaft composed of 13 ebony rods laced by a silver band, representing the 13 original United States. In 1857 a pair of tall, thin axed fasces found a place on the wall behind the Speaker’s Podium in the House chamber, a symbol meant to emphasize the strength of that Union—and, in the eyes of many, the abolitionist movement as well. The 1950 makeover substituted two heftier bronze fasces wreathed in laurel, resembling the rods and axe on the reverse of the recently retired “Mercury” dime piece (1916-1946).

This decision to make more conspicuous the fasces on the “frontispiece” of the House chamber is surprising in the post-World War II context. Beginning in 1919, Benito Mussolini had tried to make the fasces—which he perversely understood as representing “unity by means of authority”—a ubiquitous symbol in Italy of his Fascist party. After seizing power in 1922, he succeeded in jamming the fasces into almost every crevice of Italian life until his regime collapsed in 1943. Later, when Mussolini headed the Repubblica Sociale Italiana (RSI), a Nazi puppet state in north Italy, he revived an early form of his emblem. Strikingly, after Mussolini’s death in late April 1945, there was no comprehensive effort in Italy to eradicate the seemingly innumerable representations of the fasces.

I am aware, however, of only one example where new fasces appear in public art in the postwar era: Scottish sculptor Alexander Stoddart’s two identical casts in bronze of a heroic statue of John Knox Witherspoon (1723–1794), each dedicated in 2001. Witherspoon was a Scottish Presbyterian cleric who for twenty-six years led Princeton University, the only clergyman and only college president to sign the Declaration of Independence in 1776 and the Articles of Confederation in 1777. One of Stoddart’s ten-foot statues of Witherspoon was placed at the entrance of the campus of the University of the West of Scotland in Paisley, the town where the project originated. The other was positioned prominently on the campus of Princeton University.

Witherspoon is portrayed as a powerful and authoritative figure, his posture erect as he preaches from a tall eagle-style lectern, his gaze (like that of Nancy Pelosi in Sherr’s portrait) fixed on the horizon. This brings us to a novel aspect of Stoddart’s sculpture. The lectern’s thick shaft is formed from an axe-less fasces, with a bundle of sturdy rods bound by two horizontal bands. It is set on a double base, to the rear of which a stack of five sculpted books is propped, four of which show their spines—on the top, more than double the thickness of the rest, and differently positioned, a volume titled Cicero, then Principia (i.e., of Isaac Newton), Locke, and Hume. The statue also offers an unexpected (and unnoticed) visual trick. If one stands a little to the left of the eagle’s head as it peers down from the top of the lectern, the Cicero volume appears against the fasces as if an axe-head.

“The fasces represents Witherspoon’s activities as a statesman,” specified a matter-of-fact Princeton University press release just before the November 2001 US dedication. But what first sparked serious criticism of the monument was the findings of the Princeton & Slavery Project (established 2013, website launched 2017) that Princeton’s first nine presidents, including Witherspoon, all owned enslaved individuals. It soon was noted that the didactic plaques on the Princeton pedestal omitted that fact.

An open letter of July 2020, signed by over 350 Princeton faculty members, included a demand that the university’s administration remove the statue; a 2022 petition signed by several hundred community members concurred. In response, the university’s Committee on Naming has initiated a series of listening sessions and panel discussions, before making a recommendation to the institution’s trustees on what (if anything) to do with the statue. I have been unable to find concerns voiced specifically about the fasces-lectern. It seems likely that its provocative presence remains unnoticed.

Ron Sherr’s depiction of the fasces in Nancy Pelosi’s portrait and Alexander Stoddart’s incorporation of the device in his John Witherspoon monument plainly are two different matters. Sherr in his portrayal of the first woman to serve as Speaker takes great pains to leverage historical attributes of the House chamber, choosing a highly distinctive perspective to squeeze a number of long-standing emblems of institutional strength and prestige into a single frame. In contrast, Stoddart’s work introduces a fasces for Witherspoon in a jarring effort to reappropriate the pre-Fascist fasces as a symbol of legitimate authority. As Stoddard said in 2000: “I feel an obligation not to leave well-made art in the grubby hands of Benito Mussolini.”

It seems too late to ignore or undo Mussolini’s massive misappropriation of the fasces to promote his totalitarian ideology. Indeed, in the years since Stoddart and even Sherr completed their works, some extremists on the right have taken the fasces as a still-living symbol to animate practical action. At the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, one hate group flaunted on its shirts and flags fasces expressly modeled on those of the Nazi-dominated Repubblica Sociale Italiana. In the wake of Charlottesville, the white nationalist Patriot Front has been displaying as its emblem a ring of 13 stars encircling a stylized Mussolini-era fasces. Such representations have nothing to do with the use of the fasces in traditional American political iconography. There is no good reason after the defeat of Fascism to provide a future for new fasces.

T. Corey Brennan is a professor of Classics at Rutgers University; his most recent book is The Fasces: A History of Ancient Rome’s Most Dangerous Political Symbol (Oxford University Press, 2022).

Image Credit: Nancy Pelosi, oil on canvas, Ron Sherr, 2014, Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives