The divide between them is wider than you might suspect

Progressivism: The Strange History of a Radical Idea by Bradley C. S. Watson. University of Notre Dame Press, 2020. 276 pp., $30.00 (paperback)

Ideas matter—but perhaps not as much as intellectuals like to believe.

John Maynard Keynes, brilliant in his own right, captured the sentiment of most intellectuals when he declared that only ideas matter in history. He ended his classic The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936) with these words: “But, soon or late, it is ideas, not vested interest, which are dangerous for good or evil.”

As his biographer Robert Skidelsky observes in his overview of economic thought and policy Money and Government: The Past and Future of Economics: “The relationship between ideas, circumstances and power is one of the most complicated questions in the social sciences.”

For scholars of history and political thought this relationship between ideas and context presents an even hoarier problem. Determining the influence of ideas within a historical context presents multiple problems that can easily lead to specious results.

A student of history can be misled by seeing a prominent idea circulating among intellectuals and then linking this idea to a current or later social or political phenomenon. This problem is apparent in a series of studies on modern progressivism undertaken by scholars associated with the Claremont Institute—specifically Charles R. Kesler, Ronald J. Pestritto, and Bradley C. S. Watson.

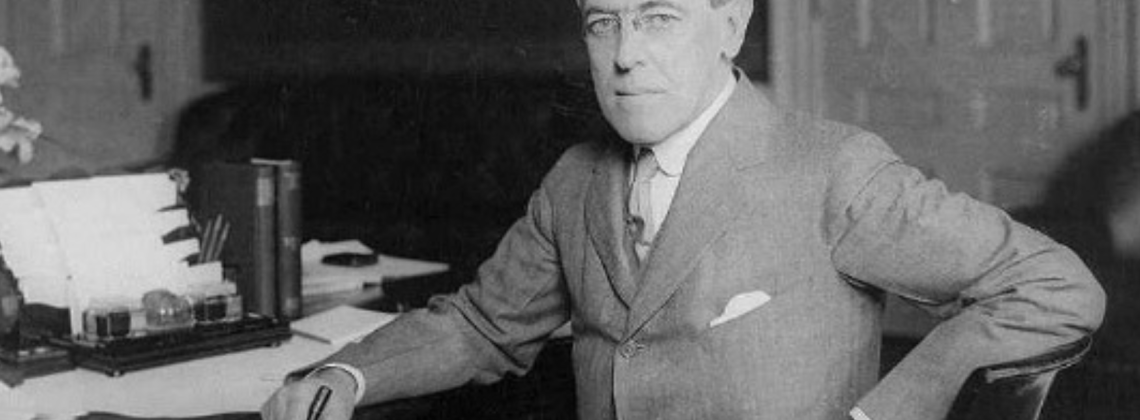

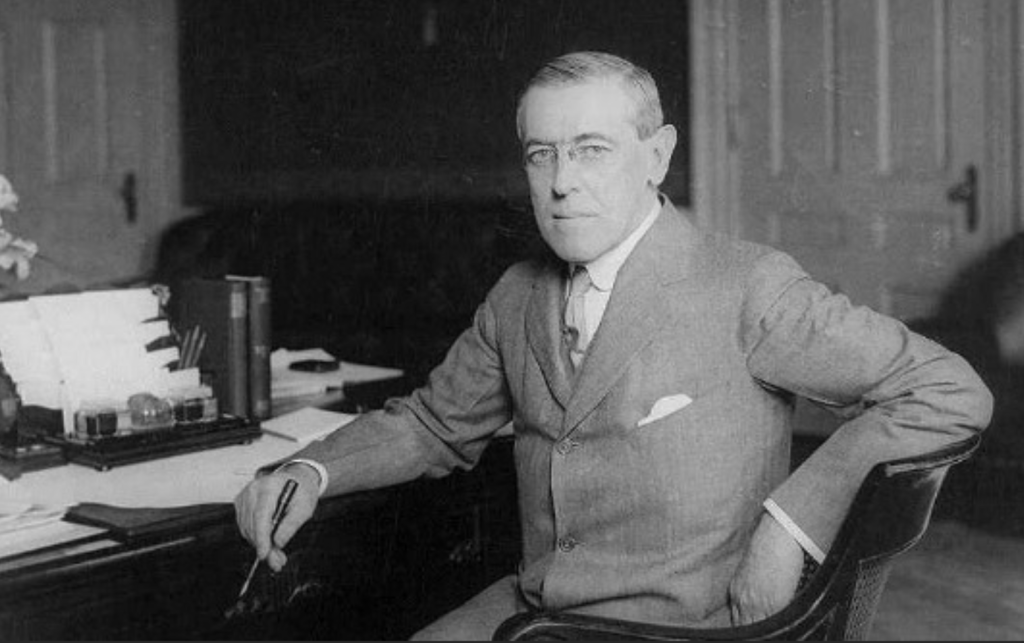

These scholars provide astute insights into modern American progressivism, tracing the roots of today’s progressivism to the turn of the 20th century, specifically to Woodrow Wilson. In Progressivism: The Strange History of a Radical Idea, Watson summarizes the argument as follows: “The progressives, as progenitors of modern liberalism, claimed that the new conceptions of the nation, role, and limits (or lack thereof) on national government were needed for problems perceived to be wholly new—especially, in the beginning at least, economic problems.” From Woodrow Wilson’s project of an enlarged government, overseen and administered by the new elite of professionals, came subsequent progressive reforms in the New Deal, Great Society, and up to today under the Obama-Biden presidencies.

Watson contributes to Claremont School scholarship by exploring the insidious nature of progressive ideas in the American academy. He offers a powerful critique of how Woodrow Wilson’s historical relativism and challenge to traditional constitutional principles as an obstacle to political, economic, and social progress became rooted in the American academy. He notes that intellectual progressivism expressed itself in the late nineteenth century in the confluence of social Darwinism, Hegelianism, and pragmatism. Watson offers a pointed critique of this progressive synthesis, which came to dominate key academic disciplines—including history, law, and political science. His book offers a pointed historiographical and intellectual history.

Following the Claremont School’s critique of Wilsonian progressivism, Watson posits a direct link between Wilsonian liberalism and contemporary progressivism. This argument is by no means intellectually facile and should not be dismissed out of hand. The focus on political thought, however, raises important methodological problems that confront all intellectual historians and students of the history of political thought.

First, are ideas primary movers in shaping history? Or are they seized upon by intellectuals and policy influencers to provide a rationale for a movement already occurring?

The second problem is related to the first: Would a political or social current have occurred without the intellectual concept or theory in the first place? This question leads to another even more complex issue that confronts every historian: finding a direct link between something happening in the world of ideas at the same time a cultural, social, or political trend or event is occurring. Just became “A” and “B” occur at a certain point in history does not mean they are necessarily linked in any causal way. Keynesianism itself presents a case in point.

Few doubt that Keynes’s The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money asserted great influence when it was published in 1939. Keynesianism was widely accepted by professional economists at the time. In America, Keynesians became more Keynesian than Keynes, arguing that deficit spending could be unlimited. Keynes understood that deficit spending and national debt presented an inherent inflationary problem if not contained. American Keynesians, such as Alvin Hanson and later Paul Samuelson, maintained that deficit spending and national debt could be sustained for long periods of time because debt was something owned by the nation.

Without going into the complexities of their arguments in favor of deficit spending, the question of how much Keynesian theory influenced their views arises. Before Keynes published General Theory, many (but not all) American economists were arguing for the necessity of deficit spending for economic revival in the midst of the Great Depression. Indeed, deficit spending as a remedy for economic depression had a long theoretical history dating back to at least the 1919 downturn, if not earlier. Keynes provided an intellectual foundation for deficit spending.

In the post-World War era, conservative journalists and a few conservative/libertarian economists railed against Keynes. Journalist Henry Hazlitt’s Economics in One Lesson (1946) and The Failure of the ‘New Economics’: An Analysis of Keynesian Fallacies (1959) became required reading within the small American Right in the early years of the Cold War. Conservative and libertarian intellectuals saw Keynesian ideas as sowing the seeds of future economic collapse. They too placed great weight on the role of ideas in history.

By imparting great power to the role of ideas in policy, the critics of Keynes did not ask the following questions: Would the Roosevelt administration have pursued fiscal policy based on budgetary deficits, especially after the 1937 recession, without Keynes? Would economists such as Hansen have advocated the need for deficit spending if Keynes had not published his General Theory three years earlier? The answer: most assuredly so. They did not need Keynes to be convinced that deficit spending policy was warranted by the Roosevelt administration. Would Johnson’s Great Society programs that led to accelerated deficits have happened without Keynesian theory? Most assuredly so.

Keynesian economic theory should not be dismissed, however, as an economic concept of importance. Generations of students were taught Keynesian economic theory through Paul Samuelson’s textbook Economics: An Introductory Analysis. First published in 1948, it dominated the classroom market, selling over four million copies in forty different languages. Students learned to accept government fiscal policy as the major instrument for economic growth and prosperity. A side effect of this instruction in Keynesian economics was the downplaying of monetary policy, which took second fiddle to fiscal policy in the scheme of things. Only stagflation in the 1970s broke the Keynesian stronghold in economics, but not entirely.

Freudianism in America offers another example of how ideas can be translated within a different historical and cultural context. In addition, Freudianism presents a case of how an idea can be given too much credit as causing social and cultural change that would have occurred with or without the theory.

Just as American economists became more Keynesian than Keynes, American Freudians became more Freudian than the creator himself. As historian Nathan G. Hale shows in his two-volume study of Freud in the United States, Freudian theory based on psychoanalysis became widely accepted in the United States, especially in the 1920s. American Freudians translated Freud to mean that sexual repression lay mostly at the root of mental health neurosis. Freudian theory, emphasizing sexual repression, exerted a major influence on American intellectual and cultural life.

Clarence Darrow introduced Freud, sexual repression, and abuse in the courtroom in 1924 in defending Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb in the murder of a fourteen-year-old boy. Darrow’s use of Freud saved the lives of Loeb and Leopold from the death penalty. Freudianism became a useful tool for understanding political behavior, specifically in relation to fascism. Theodore Adorno and Erich Fromm, associates from the Frankfurt School, applied Freud to attack the political right. Adorno’s concept of the authoritarian personality as sexually repressed became a central concept in explaining the rise of fascism. The authoritarian personality concept was widely accepted in social psychology, sociology, and political behavior course. Frankfurt School philosopher Herbert Marcuse synthesized Marx and Freud in his Eros and Civilization (1955), which found a readership among the 1960s New Left generation.

Again, questions arise about the chicken and the egg. Would the Jazz Age, Flapper Culture, and the breakdown of Victorian sexual mores occurred without Freudianism having been introduced to America? Most assuredly so. With or without Freud, American mores were changing well before the introduction or popularity of Freud. Counterculture in the 1960s did not need Freudian Wilhelm Reich to change American sexual mores.

This brings us back to Charles R. Kesler, Ronald J. Pestritto, and Bradley Watson, who find a direct link between Wilsonian liberals and contemporary progressives. These scholars astutely characterize progressive thought as introducing new concepts about the constitutional order, government power, and individual rights into American intellectual life and general political culture. They are correct in showing that progressives at the turn of the twentieth century and progressives at the turn of the twenty-first century shared a faith in using governmental power to address societal ills.

Finding shared sympathies and apparent continuity, however, assumes a linearity to progressivism that fails to distinguish the older progressive tradition in the early-twentieth century from the new progressivism that emerged in the 1960s. Only by understanding that break—and the radicalism that emerged in the 1960s and continued to take root in the following decades—can we fully understand the current political situation.

The fundamental difference between the older progressive tradition and the radical progressivism that emerged—Old Progressivism and New Progressivism—is one of context. Older Progressives primarily sought to address the ills of industrial capitalism; New Progressives focused on what they saw as the problems of postindustrial capitalism. The central issue for the Old Progressives was one of scarcity; the New Progressives viewed the nation’s chief problem as one of affluence. New Progressives seek to restrain affluence by controlling the cars we drive, the lightbulbs we use, the foods we consume, the health care we receive, and the houses we live in.

Early twentieth-century reformers, such as Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, addressed the problems of unemployment, poverty that came with age and widowhood, abuses of child labor, and dangerous consumer products with a regulatory and welfare state. Their views and solutions to problems related to monopoly capitalism varied, as seen in the differences between Wilson’s call for New Freedom and Roosevelt’s call for New Nationalism. Progressive like Herbert Hoover in the 1920s proposed an associative order in which civic and business organizations cooperated with government at the municipal, state, and federal levels to promote the general welfare.

Nonetheless, the Older Progressives agreed that corporate monopoly presented a problem for industrial capitalism. They differed, however, on how to address this problem. The New Deal in the 1930s made all too apparent the differences among progressives on the monopoly problem. Proposed policy solutions ranged from imposing greater efficiency on corporations, cartelization of industry, and trustbusting.

In the 1930s, Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal built on this reform tradition by providing a “safety net”—old-age pensions, unemployment benefits, and welfare payments. Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society went further in the 1960s, extending grants and loans to college students, establishing the Jobs Corps, creating Medicare and Medicaid, and declaring war on poverty. But this progressive tradition did not seek to dismantle capitalism itself. Even the New Deal, for all its statist sympathies, refused to nationalize banks or industries during the worst global economic crisis in history.

The progressive agenda that emerged in the 1960s was much more radical and all-encompassing. Where earlier progressives were concerned mostly with the failings of industrial capitalism, the new activists of the 1960s addressed the problems of a postindustrial order, which were related more to affluence than to scarcity. The range of concerns thus expanded beyond poverty and inequality to include corporate greed, toxic waste, unsafe consumer products, environmental abuse, overpopulation, and many other issues. These radicals disparaged consumption and corporate capitalism.

The roots of New Progressivism lie in a strategy that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s to challenge the American economic order. Indeed, these activists denounced mainstream liberalism as the enemy of reform. Influenced by a rekindled interest in Marx, they saw the New Deal regulatory state as benefiting large corporations and the New Deal welfare state as only an instrument designed to maintain class privilege.

The New Left that came of age in the 1960s was not an extension of Roosevelt-Wilson progressive reform. Nor, for that matter, was it a continuation of New Deal or Great Society liberalism. New Progressives employed the welfare-regulatory state built by the older progressives to expand governmental control over health care, consumer products, housing, transportation, and the environment. New Progressives used political rhetoric similar to the older liberal tradition—equity, social justice, and opportunity—but they welcomed a New World Order overseen by global economic and political elites.

One of the ironies of New Progressive rhetoric is that while denouncing the rich and powerful, corporate greed, and elitism, the New Progressives formed alliances with large corporate interests who saw opportunity in the regulatory state. Big Pharma and Big Insurance signed on to Obama Care. This alliance is captured in the very description of Woke Capitalism in the twenty-first century. This global New World Order is far different from Hoover’s Associative State, which required the cooperation of small commercial interests and government.

One of the most obvious differences between Old Progressivism and New Progressivism concerns issues of race. Race was not the focal point for most Old Progressives, especially in the North, although Woodrow Wilson was an out-and-out racist. So were many Southern Progressives. School segregation for students of Japanese ancestry students became an issue in San Francisco, but in many respects it became a foreign policy issue between the United States and Japan.

Race has been a primary focal point for New Progressives. Diversity, equity, and inclusion are central to the New Progressive agenda. Claremont scholarship on progressive political thought cannot account for this. Wilsonian racism does not show a linear trajectory—or any trajectory for that matter—in progressive thought. If it does, it is not accounted for by the Claremont School. Only historization of the rise of New Progressivism—its roots in the 1960s Civil Rights and the Black Power Movement—explains the current near-obsession with race among today’s progressives.

These objections notwithstanding, the Claremont School, as represented by Charles R. Kesler, Ronald J. Pestritto, and Bradley C. S. Watson, has much to tell us about progressivism as it emerged and developed in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. These authors display an intellectual prowess missing in much of academic scholarship these days. Watson’s pathbreaking Progressivism: The Strange History of a Radical Idea is especially powerful in detailing the pervasiveness of progressive bias in American historical scholarship.

Whatever the differences between the Old Progressives and the New Progressives, the Claremont School dissects with razor sharp acuity the hostility of progressives toward both the Founders’ Constitution and individualism. But both the Constitution and individualism are central to well-ordered liberty and are essential to our nation.

Donald T. Critchlow is Director of the Center for American Institutions at Arizona State University.