A recent kerfuffle between pro-abortion rights Catholic legislators and the American Catholic bishops offers a convenient reason to consider a pesky little word: conscience.

The legislators cite the Catholic Catechism (paragraph 1790) to the effect that a “human being must always obey the judgment of his conscience.” Not doing so, the person “would condemn himself” (the legislators alter the Catechism’s language to make it gender inclusive). In supporting abortion rights, argue the legislators, they are simply following their conscience, their sense of right and wrong. In the name of “social justice, conscience, and religious freedom” they must voice support for abortion rights.

The bishops counter with two basic points. First, the Catechism of the Catholic Church argues that human life is sacred and “must be respected and protected absolutely from the moment of conception.” Further, a fundamental tenet of a just “civil society and its legislation” is legal protection of life “from the moment of conception” (see paragraphs 2279, 2273). Finally, conscience is not a license to do what one wants. Instead, conscience must be “informed and moral judgment enlightened.” Conscience should be formed by “the Word of God” and prayer (see paragraphs 1783 and 1785 for these citations).

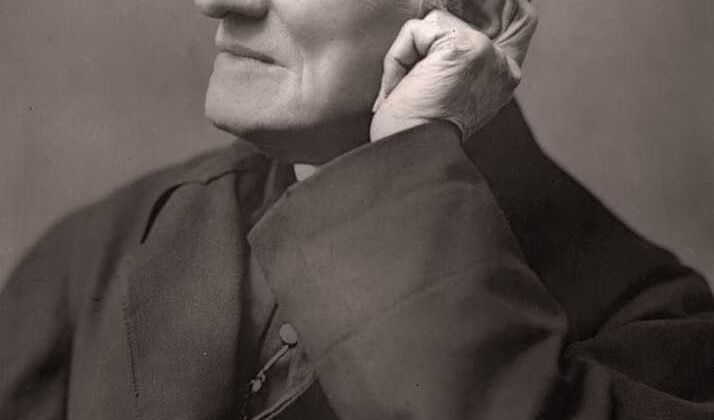

To address this conundrum perhaps we should consult that great statement on conscience, Saint John Henry Newman’s eminent discussion of conscience in his Letter to the Duke of Norfolk.

Newman begins his discussion with a consideration of eternal and natural law. Drawing from Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, Newman argues that eternal law is the “Will of God,” while the natural law is (quoting Aquinas) “an impression of the Divine Light in us.” This, says Newman, is conscience–namely the human’s knowledge of the Divine Will, implanted in our nature by God. Newman says this light may be “refracted” by passing through each individual’s “intellectual medium”; it does not lose its status as Divine Law. Newman agrees, therefore, that “it is never lawful to go against our conscience” as that is akin to going against God’s will.

But Newman makes a quick distinction. Conscience does not mean doing whatever you think is right. In Newman’s view, they are mistaken who think of conscience as “a desire to be consistent with oneself.” He chides those who think of conscience as “the right of thinking, speaking, writing, and acting according to their judgment or their humour, without any thought of God at all.” It is “counterfeit” to think of conscience as “right of self-will.”

Conscience is obedience to “a divine voice.” It would seem, then, that one has to be attuned to that voice. We can understand Newman’s point via analogy. Like many people, I suspect, I enjoy both jazz and classical music, but having little musical training and having my musical ear educated by popular music, I am sure I do not appreciate more complex music to the same degree as those with a better educated ear. When it comes to better music, I tend to “know what I like” while not really giving a musical reason for it.

Sports might be another analogy. We watch sports we really know differently than sports in which we are casual fans. I have watched, played, and coached baseball. That helps me appreciate the game. This is true for football as well. Although I’ve never been anything but a fan, my fandom has been fairly serious so that my enjoyment of the game is the strategy and one-on-one matchups rather than the spectacle (hint: if you want to really get football, watch the line of scrimmage, not the ball). On the other hand, when I watch, say, a volleyball game or a tennis match, I know there are strategies and plays, but on the whole it’s just people knocking a ball over a net. I still enjoy it, but I know I am not really seeing what is going on.

How does this relate to conscience? Newman argues that your conscience is not just “what I believe to be right” but “what I believe to be right, after careful discernment and gathering of information.” As with appreciation of music or sport, you can only use your conscience if you’ve taken time to understand and appreciate what God’s will may be in a given situation. Recall, conscience is not doing what you feel is right, but correctly discerning what is God’s will in a given situation. Think of conscience as a muscle: it must be exercised or it becomes flabby and weak.

Conscience is not an excuse to believe false things or act unjustly. Obviously, if I kill my neighbor, I can’t say, “Well, my conscience told me that his loud music justified my putting a knife in his heart.” Killing my neighbor (absent self-defense) is inherently wrong. This is akin to Aristotle’s contention that there are some actions that are impossible to do well. He raises adultery as an example.

Newman warns that our “mean, ungenerous, selfish, vulgar spirit” will often distort our conscience. We all know that each of us has a great capacity to rationalize “what I want” into “what is good,” to conveniently confuse our will with God’s will. If one disagrees with religious authorities—Newman means primarily the Pope, but one could easily substitute other authorities—one must avail oneself to “serious thought, prayer, and all available means of arriving at a right judgment on the matter in question.”

To the extent that Catholic legislators, in invoking conscience in defense of abortion rights, are defining conscience merely as “doing what I think is right,” they contradict the Bishops (authority), the Catechism, and the teaching of Newman. If I were Catholic (and I am) that would give me great pause, and perhaps cause me to reconsider my definition of “conscience.”

There is also the question of abortion itself. This is a highly fraught question, so this is probably not the place to consider its ultimate morality (whose mind would be changed anyway?), but to assess the Catholic legislators’ contentions we have to consider the nature of abortion. Is abortion, in most cases, more like Aristotle’s view on adultery–that thing that cannot really be done well, i.e., it’s intrinsically wrong? Or is it a thing that under usual circumstances is either morally indifferent or possibly good–and, therefore, something about which the public should not legislate? I’ll leave that up to readers, although it is worth noting in the intra-Catholic debate, the Catechism is quite clear: taking innocent life is wrong, the state has the duty to defend innocent life. The unborn constitute innocent life, therefore the state should pass legislation to defend human life.

The problem, as Newman indicates, is with us. We tend to view many of God’s dictates as buzz kills, God telling us what to do. But much as when we were children we often looked upon parental rules as arbitrary and constricting, as we get older and become parents ourselves, we come to the realization that these rules and restrictions are (at their best) acts of love. It is our sinfulness, our mean, ungenerous, selfish, vulgar spirit, that makes us think of God’s commandments as restrictions rather than liberating acts of love. If God, the benevolent Father, sometimes tells us to do this and not to do that, it is not because God is an arbitrary tyrant who gets his kicks telling us what to do. “Behold what manner of love the Father has bestowed on us, that we should be called children of God!”