There’s supposed to be a difference between history and heritage and historians are supposed to study the past for its own sake, not to make use of it. There’s a whole section in John Fea’s Why Study History? about uses of the past (side note: a second edition is now under way). But even professional historians get nostalgic. And every now and then, there’s something from the past you would like to make use of. It happens. In my case, I’m talking about mourning clothes.

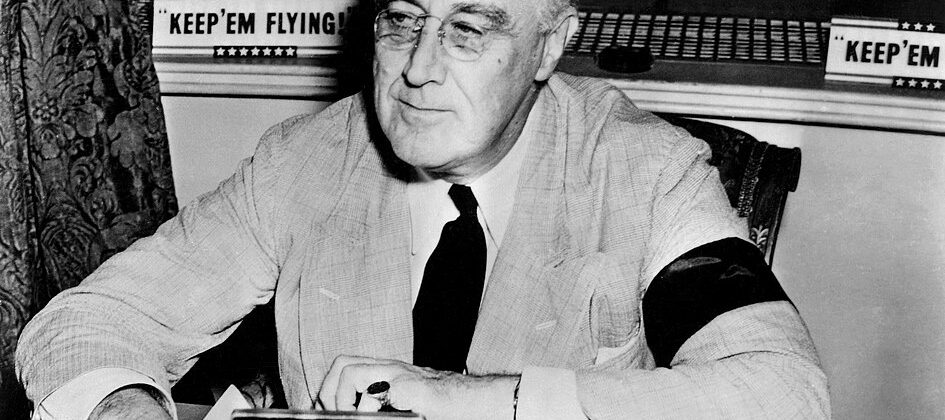

If you go back a couple hundred years in Western culture, you will find mourning clothes. You may have noticed in a novel that a widow was wearing black for a certain period of time. Or maybe you heard that Queen Victoria wore mourning clothes for the rest of her life after the death of her husband, Albert. Mourning had stages. Women wore black and eschewed most jewelry and showy things, then gradually integrated colors back into their attire, etc. Their clothes were supposed to reflect their grief. There were also mourning armbands, often worn by men for a given period of time. These lasted much longer. We see echoes of them in sports today—when athletes will wear some version of them for a game or a series of games.

I think we should bring back some form of mourning clothes, at least the armband. While it’s true that the full period of mourning and the strict expectations for clothing could be burdensome and oppressive, it’s also true that mourning attire allows people to publicly express their grief. You are deeply affected in the six months after a spouse or parent or sibling dies, even after. It’s hard for people to go about their lives like nothing happened. Mourning attire is a reminder that something did happen. You don’t have to be bright and cheery.

All the time on social media we see some version of the same quote, attributed to a wide variety of people: “Be kind, you never know what someone else is going through.” We really don’t know. And it’s very easy to forget this quote. But if you saw an armband on that coworker who is unusually behind schedule or overly distracted, you’d be reminded right away to have some compassion. If you met a stranger wearing one at a party, you might be a little more savvy about your opening questions. And if a cashier with an armband seemed to be struggling with the basics, you’d probably be better at keeping calm.

A mourning armband could draw unwanted attention. Not all mourners might like sharing anything about their personal loss. It would certainly take Americans a while to get into the habit of seeing them and knowing what they are and knowing what not to say. There would be a real learning curve. But wearing the armband could easily mean not having to explain certain things. It could be a way to spare the wearer from saying anything in some situations. The armband says it all.

Being legalistic about mourning attire wouldn’t help anyone, but having mourning attire could help acknowledge that grief is long. Our society has a short attention span. People seem to move on quickly from everything. Grief doesn’t work that way. Ask Hamlet. But we don’t have many ways of showing care over the long-term. A mourning armband could be a good reminder for those less affected that what happened is still very much affecting those who were close to the dead.

It really is true that we don’t know what the people around us are going through. It probably wouldn’t be helpful to know who skipped a meal or overslept or has a gambling addiction. But we could stand to do a better job of acknowledging the big changes in people’s lives and giving them the space they need for the time it actually takes. Grief is long and a mourning armband could help us better love those around us.

I’m reminded of this practice every time I re-watch “It’s a Wonderful Life,” where black armbands are present after Peter Bailey died. I’ve always thought it was an elegant practice worthy of reviving.

The writer is right on. I have seen people at “funerals” who were dressed like for a day in the park. When my grandfather died, my grandmother was asked what she was going to do. Her reply was to wear black for a month.

“But if you saw an armband on that coworker who is unusually behind schedule or overly distracted, you’d be reminded right away to have some compassion. If you met a stranger wearing one at a party, you might be a little more savvy about your opening questions. And if a cashier with an armband seemed to be struggling with the basics, you’d probably be better at keeping calm.”

Precisely why it won’t–indeed, can’t–happen.

Under capitalism, as Marx noted, “All that is solid melts into air.” Tradition, affective obligations, consideration for the stubbornly human aspects of a human life. Instead, the standard is “professionalism,” which in this case means the submergence of all the things about the individual worker outside those dictated by the job being done.

Something like mourning, especially, which might slow you down, distract you, interfere with your ability to focus entirely on whatever the job may be, is doubly awful from the capitalist perspective, because it not only affects the worker’s productivity, it asks those who supervise, work with, or interact with that worker to tolerate and enable it, thus expanding the intrusion of “the solid” across the workplace.

But there’s a spiritual layer to its offensiveness also.

When you’re asking, “Would you like fries with that?” it’s necessary that you not only do so cheerfully, but that you convey to the customer that fries are the best thing that could happen to them in this moment, that fries will sweep away any sadness or dissatisfaction in their lives, that fries will make them blessed, that fries are the gateway to the kingdom. An armband would say “There’s something more important than fries, I have learned that and need to testify to that, and I want you to know it too, because, in fact, what this is is coming for you too, and fries can’t save you.”

Nope. No self-respecting business wants to pay an employee to spread that message. When you’re on the job, you say what they pay you to say.

The genius of capitalism is that it doesn’t just elevate work above all other human considerations, it’s downright intolerant of them: “Money doesn’t talk, it swears,” as the lyric has it, and in this situation it blasphemes: “You shall have no other gods before me,” it legislates.

So, wonderful idea, but also impossible.