What if history really does center on the least, the last, and the lost?

A History of the Island by Eugene Vodolazkin, translated by Lisa C. Hayden. Plough Books, 2023. 320 pp., $26.95

The June cover story in the Atlantic depicts the war in Ukraine as “a chance to alter geopolitics for a generation.” It’s the kind of story you’d expect to result from an exclusive sit-down interview between prize-winning journalists, Laurene Powell Jobs (Steve Jobs’ billionaire wife) and Volodymyr Zelenskyy (the current president of Ukraine and a former actor and comedian). Oh, and the cover illustration was drawn by Bono. At stake in this war, they inform us, is “not just democracy but civilization.” If the U.S. sends the right weapons now, apparently, “autocracy” and “hierarchy” everywhere will be defeated and “democracy,” “freedom,” “heterarchy,” “entrepreneurship, liberty, civil society, and the rule of law” will flourish. As Zelenskyy frames the binary, “The choice . . . is between freedom and fear.”

If only it were that easy. If only history were indeed a meaning-bearing transcript with perspicuous implications for our choices today. While the authors of this story recognize the insidious agenda motivating Vladimir Putin’s claims about “the historical destiny of Russia and its peoples,” while they criticize Putin’s “grandiose dreams about his place in history,” they indulge in fantasies about civilizational conflict in ways that mirror Putin’s self-serving, simplistic falsifications. And they never notice the irony.

Eugene Vodolazkin’s A History of the Island skewers all such pretentious claims about history as a grand and noble march toward a bright future where Important People will usher in democracy and freedom for all. And it manages to be downright funny while doing so. In brief, the novel’s conceit is to reproduce a centuries-long chronicle written by a succession of monks living on a fictional Island. Interspersed with this account are notes written in the present by the island’s king and queen, Parfeny and Ksenia.

As it happens, the royal pair has each reached the unusual age of 347. In explanation of this fact, Ksenia remarks that “some people simply live longer, for various reasons.” Due in part to their age, the king and queen are out of time; they live in the modern world, but their imaginations and sensibilities remain medieval. And their medieval notions of history stand in stark contrast to modern bluster about history’s arc. Parfeny makes his allegiance clear at the outset when he describes why the monks make good historians: “Only someone focused on eternity is capable of depicting time, and one who thinks of the celestial is the best person of all to understand the earthly.”

The differences between this medieval perspective and a more modern view are humorously sketched in an exchange that Ksenia describes between the royal couple and the publisher who is bringing out this new edition of the Island’s chronicle:

Phillip asked us how we perceive such a radical change in notions about the universe. Parfeny (geniality itself) answered that he had not noticed radical changes. Phillip (polite patience) poured himself more hot water. He did not understand how one could not see differences between the Middle Ages and modern times. They give opposite answers to all basic questions.

“There is only one basic question,” said Parfeny, bringing a cup to his lips, “and it concerns the circumstances of the world’s creation. The Middle Ages answer that the world was created by God. What do modern times answer?”

“Well, first of all . . .” Phillip’s hand moved in an arc.

“Modern times say: I don’t know,” Parfeny cued him. “And for some reason, it seems to me that science will never have another explanation.”

The din of an airplane resounded outside; the airport is not far away. Phillip involuntarily spoke louder and the conversation suddenly became a debate:

“Why, I wonder won’t there be?”

“Pure logic. Science studies only the physical world but in order to explain that world as a whole, one must leave its confines. And there’s nowhere for science to go.”

A Christian perspective on human history depends on the reality of a place outside the confines of time and on the reality of an intersection between that place and our world. As the monastic chronicle attests, prior to the introduction of Christianity the Islanders didn’t even have a conception of historical time. But as Christianity spread through the Island (in large part due to the ruler’s coercion—plenty of the Christians in this chronicle are corrupt), a sense that “human history has a beginning and is hastening toward its end” shaped the people’s imaginations. I myself tried to unpack the implications of these three modes of timekeeping—pre-Christian cyclical time, Christian time keyed to eternity, and post-Christian historical time—in the second section of my book Reading the Times; Vodolazkin shows the implications brilliantly in this novel.

The chronicler briefly summarizes the account of the world’s origins as given in Genesis, and he continues to paraphrase the Genesis narrative up through the story recorded in chapter eighteen. There the Lord tells Abraham that he will destroy Sodom and Gomorrah because of their sin, and Abraham intercedes for the people, asking him if he will spare the cities for fifty righteous people, then forty-five righteous people, then, forty, then thirty, then twenty, and then ten. The chronicler’s account concludes: “He found not ten there and so He rained brimstone and fire out of heaven on Sodom and Gomorrah and the entire surrounding area. Historical books describe many other events too, but I have referenced only the primary ones.”

Why does this chronicle conclude its summary of Genesis here? Perhaps because this episode shows both the need for godly humans to intercede for others, to mediate between God’s time and historical time, and also the shortcomings of all human efforts to fill this role. As Milton depicts in Book three of Paradise Lost, it is Jesus who fulfills Abraham’s bumbling efforts to mediate for his sinful neighbors, and the novel’s conclusion offers a similar reading of the gospel.

But at least Abraham tries to mediate between the Creator and sinful humans. Most of the rulers whose words and acts are recorded in this chronicle appear concerned only with their own self-interest, though they take great pains to cloak such narcissism in various rhetorical appeals. The humor in the book arises from the recurring gap between noble words and ignoble deeds. As official chroniclers, the monks must be restrained in reporting on the parade of princes, emperors, and chairmen who rule, but their evaluation of these charlatans comes through nonetheless. Take, for instance, this account of history professors under the chairman who chooses the title, “Your Brightest Futurity”: “The former history professors, now specialists on scientific foresight, who had already been nicknamed foreseers, told His Brightest Futurity about their work. They reported to the chairman that never before had their research taken on such a creative nature. That was the unvarnished truth.”

Or take this account of a former magician who married the chairman’s daughter (this chairman was obsessed with bees, naturally) and was on his way to taking over the government:

Valdemar had not sawed his assistants in a long time: he had transferred that sort of activity to carving up the Island’s treasury. The peculiarity of his tricks consisted of the fact that once monetary assets had disappeared, they never reappeared. And if key rings, watches, and banknotes had invariably been returned to their owners in the past, that was all different now. Valdemar astounded the distinguished public with the art of disappearances. He proposed they watch his hand, but so great was his gift that watching proved useless. In a short time, army salaries, money for road repair, and even the funds for beekeeping (the Island’s main budgetary expense) vanished without a trace.

As one would expect from such a skilled magician, he masters the levers of modern power. After his shady business deals are exposed he appears on TV and gives an impassioned speech: “He used television’s possibilities to far greater advantage than had the whistleblower. The whistleblower had the paper and dry details of the agreement on his side; Valdemar had fervent feelings on his side.” It should be no surprise that Valdemar is elected president.

The Island’s chronicle inoculates its readers against expecting to find anything really new in political or military or economic affairs. The details change a bit, but the sordid tale of greed and restless envy remains essentially the same. One loony leader is obsessed with bees and another is obsessed with horses, but both use their position to pursue their hobbies rather than serve their people. Or one colonial business scheme involves extracting oil and another involves extracting diamonds, but both enable wealthy people in other places to profit from the labor and natural resources of others. Or one dictator is supposedly killed by a crocodile and the other by a Rolls-Royce, but both convenient deaths enable the only witness to the leader’s demise to ascend to power.

This is not to say that human choices and actions don’t matter. It is to say that we tend to misapprehend which ones matter and how they matter. The events reported above the fold may not merit the weight we place on them. Rather, it’s the events that concern the least, the last, and the lost that resonate throughout the cosmos. Vodolazkin not only mocks the self-important foolishness of the people who think they shape history. He also points to the oft-hidden events that may matter more profoundly.

These sometimes come through in the careful irony of the official scribes. “Elections,” for instance, “undoubtedly influenced the flow of life but then the influence had its limits. More specifically, elections determine the name of the president rather than the president’s decisions.” But more often it’s the commentary from Parfeny and Ksenia that reveals the vertical dimension of human affairs. They choose repeatedly to appreciate the evening light or to lovingly describe the beauty of a blossom or to linger over their chaste love for one another. They place as much moral weight on the challenges of living with an annoying roommate (after they have been pushed out of power by his Brightest Futurity and sent to a communal house) as they do on difficult political decisions.

Reading the juxtaposition between the events that fill the historical chronicle and the royal couple’s commentary offers the experience of living outside of one’s time. Parfeny and Ksenia experienced ways of life and people and events that belong hundreds of years in the past, and this temporal displacement enables them to inhabit the present differently from their contemporaries. Time and again it is the lust for “something new!” that ushers in destructive political or cultural turmoil. The people grow bored and like the Athenians with whom Paul speaks in Acts, they want a diversion. Parfeny believes that “patience is the most practical measure” in response to this human problem. He and Ksenia embody such patience, refusing to get caught up in the fads and trends, the political movements and conflicts that colonize the attention of the present.

While most of us won’t have the opportunity—or, perhaps more accurately, the burden—of living three and a half centuries, we can feed our imaginations on wisdom and perspectives that belong to other eras. At the same time, we cannot mistake knowledge of history for genuine wisdom. The “knowledge of the past is essential for those holding power,” writes one chronicler. He then wryly adds, “it is also fair to say that knowledge of history has yet to prevent anyone from making mistakes.”

But perhaps a recognition that, as one monk notes, “history’s primary event was the incarnation of Christ,” would establish the proper framework for understanding human history. If we can live according to this conviction, we might be able to cultivate personal lives rooted in eternal truths rather than temporary moments. Such formation may enable us to intercede for those who have lost sight of ultimate matters in a frenzied striving after what promises to satisfy immediate lusts and desires. Such is the condition of the inhabitants of Sodom and Gomorrah. Such is the condition of the inhabitants of the Island who itch for what is new and so consign themselves to shuffle from one form of oppression to another.

Neither the past nor the future belong to those who lay claim to them for self-interested rhetorical effect. All time belongs to the Word who spoke it into existence, who entered it as Jesus of Nazareth, and who will one day return as the King. The moving conclusion to the novel suggests that those who patiently focus on eternity can chuckle in response to pundits and politicians who make claims about historical destiny or the arc of history, and they can intercede for those who suffer the consequences of these grandiose claims. It’s those who are out of sync with history’s rhythms who may be able to avoid being caught up in them and instead offer redemptive and prudent responses to the excesses of the moment. Vodolazkin’s heroes in this book, as in his previous novels, are the holy fools whose eyes are fixed on a horizon of meaning that lies orthogonal to the arc of history.

Jeffrey Bilbro is an Associate Professor of English at Grove City College and website Editor-in-Chief of Front Porch Republic. His books include Reading the Times: A Literary and Theological Inquiry into the News, Loving God’s Wildness: The Christian Roots of Ecological Ethics in American Literature, Wendell Berry and Higher Education: Cultivating Virtues of Place (written with Jack Baker), and Virtues of Renewal: Wendell Berry’s Sustainable Forms.

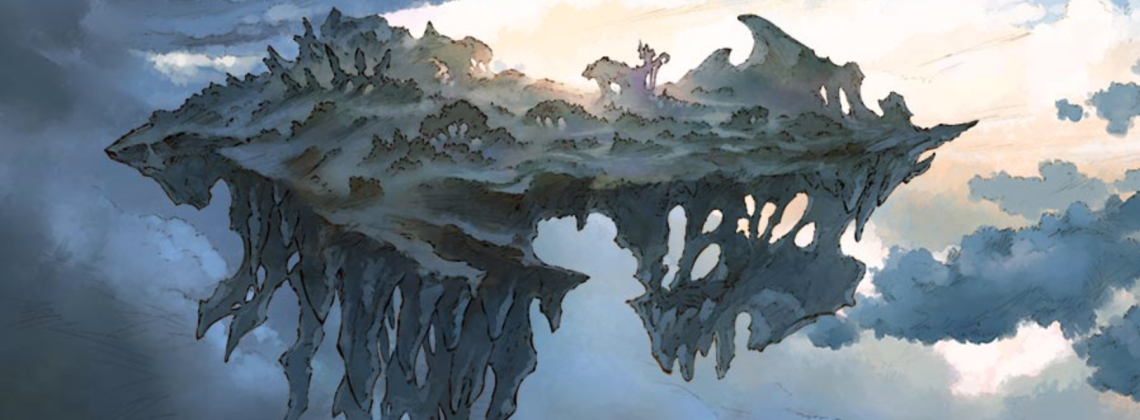

Image: GBF Wiki Mist Shrouded Island