In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, people doing early anthropology were very interested in climate and environmental conditions, but in very different ways from today. Early anthropologists connected geography to the nature of the people living there. Now, this makes some sense if you’re thinking about things like disease resistance or what kinds of houses people build, but the early anthropologists thought it indicated temperament and what kind of government you could have. Rousseau was pretty sure that democracy would be a disaster in a warm climate where people were naturally more “fiery.” Nowadays, we probably wouldn’t ask what types of temperatures you’ve lived in if you ran for president. But differences in geography do indicate a different context.

We can still learn something more about ourselves and our place in the world through a better understanding of our environment. One place we can begin is with American animals. A few good books on that path are Coyote America by Dan Flores, The Founding Fish by John McPhee, and American Buffalo by Steven Rinella. There are others.

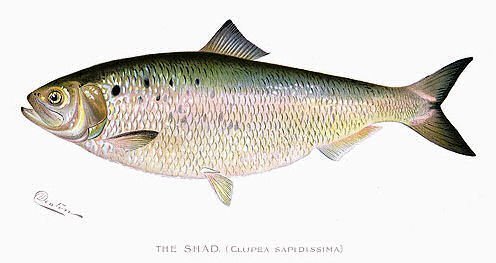

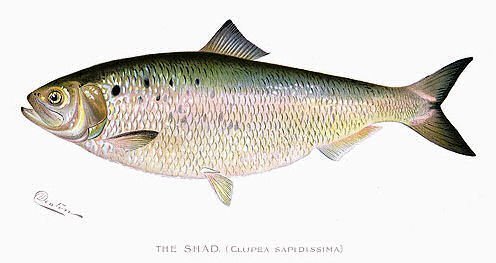

Buffalo, shad, and coyotes. They are interesting animals, some of them quite charismatic and even bearing metaphysical associations. They are all perfectly adapted to the American continent and demonstrate a remarkable relationship with their environment. The plains are different with and without buffalo. It’s also interesting just to learn how these animals operate. Adult shad live in the ocean and return to the freshwater rivers and streams where they were born to spawn—see a shad swimming upstream and you know what it is up to. But animals can also tell us some things about ourselves.

One thing we can learn from American animals is about how our environment works and what it is doing. You’ve probably seen a video about how much changed once wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone—every animal plays a role in the ecosystem. If we watch the wild animals, we might better understand the ecosystem. No doubt you’ve noticed in the past few years that there are coyotes everywhere. They’re in every state other than Hawaii. The expansion of the coyote empire tells us something is happening. Deer have increased. So have trees on the East Coast. Paying attention to animals can help us discern changes in our environment.

Animals also tell us something about ourselves. Buffalo are majestic creatures who can handle cold weather amazingly well, but we don’t talk about buffalo for very long before we talk about ourselves. People hunted the buffalo almost to extinction—for sport and for hides. The story of the buffalo is part of the story of the West. Americans used to love shad and consider it a delicacy—now many people decline to fish for it, because it has so many bones. Our feelings about shad reveal shifts in our tastes. The presence and absence of shad also reflects not just their traditional territory, but whether or not we’ve put in dams or damaged their rivers. Our stories are intertwined. Shad have even been credited with supporting the American troops in the Revolutionary War. Animals can help us see and share our human story.

As little loved as they are, we can learn a lot about ourselves from our relationship with coyotes. Neither wolf nor fox, coyotes are an indigenous animal long known as a trickster. Some Native American tribes recognized a coyote god. Coyote became much less revered, but not less recognized as a trickster. Considered a nuisance, the United States has attempted to exterminate coyotes, but we never succeeded as much as we did with the buffalo and wolves. In fact, it is essentially impossible to exterminate coyotes. No matter how many you kill, they will compensate for the numbers. If you read Coyote America by Dan Flores, you will realize that coyotes are kind of incredible. If you kill 70% of a coyote population in a year, they’ll basically say “there’s always next season” and be back. Why we want to kill coyotes, and why we can’t, is pretty informative about us as a people.

In some ways, wild animals can help reveal our values. In a simple economic sense, they reveal demand at a given time. Are we hungry for roe? Wanting fur coats? Seeking the thrill of the hunt? Desirous of a beaver hat? Trying to protect our livestock? Do we need whale oil for our lamps? In another sense, our relationship with wild animals tells us about what we consider acceptable. Is it ok to poison a coyote? Is it ok to exterminate the wolves in a given area? Must we use the buffalo we shot or can we leave them to rot? Should there be protected spaces for animals and wilderness? Do we want to domesticate this dog? Our complicated relationships with wild animals over time show us cultural shifts.

Unlike domesticated animals, wild animals can also somewhat serve as models. No one wants to emulate the farm-raised tilapia or the fish tank guppy. But you could do worse than to be somewhat like a shad. Shad remember the stream they were born in. They are extremely tied to place. They appreciate a clean, flowing river. Those are good values. People cheer for the roadrunner rather than Wile E. Coyote, but his resilience is admirable. Coyotes are infinitely adaptable and can’t be crushed. Everyone thinks the dire wolf is great, but they’re all dead. Considering our ability as humans to be a threat to bears, wolves, eagles, sharks, and such, and our inability to destroy coyotes, we could have a few more high school sports teams named after coyotes.

It’s not uncommon to hear someone mention that the money we spend on pet food tells us a lot about who we are as a country. That’s true. But we can learn quite a bit about our country from our wild animals, too. Wild animals can help us better understand our environment and our relationships with them give us another lens for viewing our history. Every now and then they might even inspire.