Wendell Berry’s agrarian vision and the life of a pediatric surgeon

For those of us familiar with the work of Wendell Berry, his voice stands out for its nearly singular call to values and vision that are all but lost in contemporary America. Decrying “the economics of self-interest and greed,” Berry’s sixty-plus years of writing amount to something like a book of prophecy, both in its persistence and its prediction of the ruin of many precious things. And those who have ears to hear and eyes to see cannot help but recognize the symptoms of ruin all around them.

*

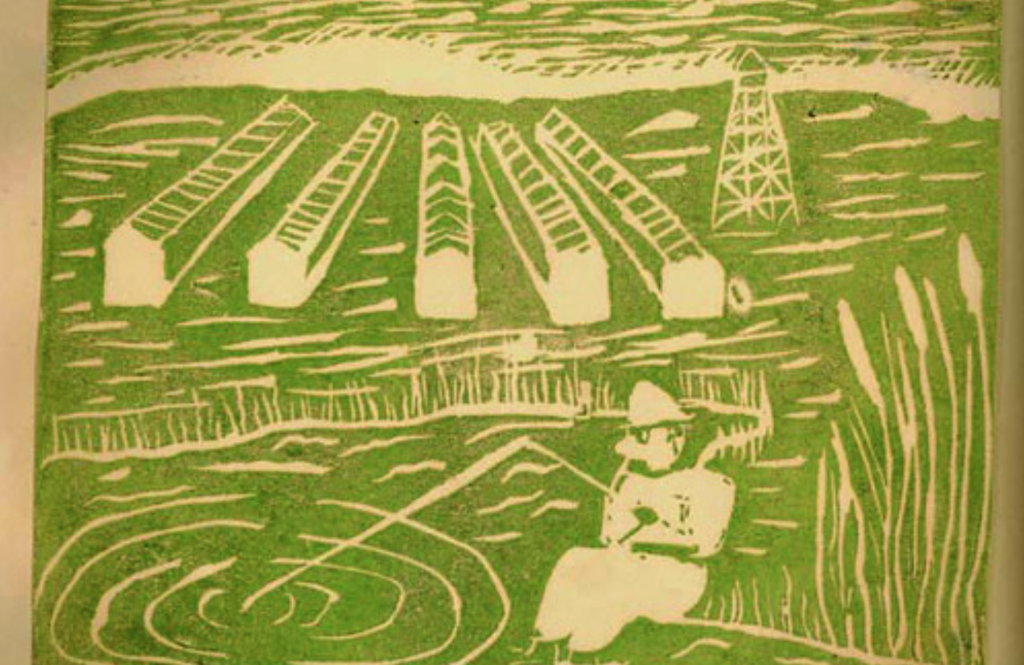

On my own native soil of Louisiana, the results of what Berry calls “the unsettling of America” are evident everywhere—culturally, agriculturally, environmentally.

To cite but one dramatic example, Louisiana has lost nearly 2500 square miles of wetlands to coastal erosion, and we continue to lose 20,000 acres every year as a result of un-thinking exploration, exploitation, development, and abandonment. These are the manifestation of what Berry calls “a political brain disease that causes people in power to think that anything that makes money or ‘creates jobs’ is good.”

But in many ways, my state is like any other state, including Wendell Berry’s Kentucky: a series of congested and dirty cities filled with fragmented communities and connected by highways bristling with billboards, lined with litter and dotted with the structural ruins and cultural remains of what once were thriving rural communities.

*

A few years ago, I made a round trip from the tiny community of Linton, in western Kentucky, to the equally tiny community of Crab Orchard, in central Kentucky. As it happened, I spent the day listening to Berry’s novel, A Place on Earth, and I was acutely aware that I was hearing a voice that came from the hills and hollows and pastures and fields around me. It was, in fact, a beautiful drive.

Along the way I passed the majestic edifice of Saint Catharine College, the now defunct institution that, until its recent closure, housed the Berry Farming Program. The reasons for its demise—spending beyond its means and taking on unsustainable debt—call to mind many of the ills that Berry has so strongly condemned. And, though I don’t have the eye to see it all perfectly, I had some sense of why Berry might say of rural America that “driving through it has become a depressing experience.”

Back in western Kentucky that evening, I came across several Amish folk on the road, also making their way home through the dark, but in horse-drawn carriages, the riders leaning on one another and blanketed against the cool night air. And as I passed one buggy, I took notice of the horse, a strong-looking chestnut mare. I was struck by the beauty and constancy of this creature at work—the lathered and heaving equine mass, hooves clapping against the asphalt, one after another, testifying to her steadfastness.

Meaning to be polite as I passed the carriage, I slowed down almost to the mare’s pace and, as I did, the young man driving the cart looked back over his shoulder at me, curly hair coming out from beneath a straw hat and his eyes clear and steady. In that moment it felt as though we were looking at each other across a chasm, from different worlds. And I wondered if the answers to some of our most profound problems require a kind of radical insistence, a constancy that young man knows and I do not.

*

Though I had previously read a few of his poems, I first engaged the writing of Wendell Berry while I was a medical student, more than twenty years ago. My friend and mentor, Morgan Wills, recommended that I read the short story “Fidelity,” which he rightly saw as a powerful reminder of the extent to which the hospital and the healthcare community constitutes a distinct culture, with its own language, dress, mores, hierarchies, and so forth.

The plot of “Fidelity” revolves around the death of Burley Coulter, the senior member of the Port William “membership”—that is, the community of the fictional town in which most of Wendell Berry’s stories take place. The story begins with Burley’s family gathered around a hospital bed, where “the old man . . . was lying slack and still in the mechanical room, in the mechanical light, with a tube in his nose and a tube needled into his arm and a tube draining his bladder into a plastic bag that hung beneath his bed.”

For these rural folks, the hospital was a place of bewilderment: “Their eyes met in confusion, as if they had come to the wrong place.” “Loving him, wanting to help him, they had given him over to ‘the best of modern medical care’—which meant, as they now saw, that they had abandoned him.” They, therefore, “contrive to break him out.” And they do.

For me, a small-town boy from the South, descended from dairymen and truck drivers and refinery workers, who arrived at Vanderbilt School of Medicine in an old green pickup truck, I felt more kinship with the “damned rednecks” of the story than I did with the doctors. The effect, on the whole, was an unsettling, and I was left with an abiding sense that something of value—something precious—had been lost, for rural America, for the medical community, for me. That unsettledness remains.

*

In his essay “The Pleasures of Eating,” Berry acknowledges the difficulties of reconciling agrarianism with urban life, and he offers a list of seven answers to the question, “What can city people do?” Each is a variation on his more general answer: “Eat responsibly.” Of course, what his questioners are really wanting to ask is not “what can a city person do?” but, “What can I do?” And that is a more important and a much more difficult question.

For me, a pediatric surgeon living and working in the twenty-first century, I have yet to sort out how to reconcile my vocational life to the agrarian vision.

The death of Burley Coulter is beautiful not least because it rejects the mechanical, depersonalizing, and hectic world of the hospital for the pastoral world of Port William—the “bright orderly enclosure” of the doctor’s empirical knowledge for the deeper wisdom and courage that springs from rural simplicity.

But the romantic picture holds only because, as Mat Feltner says of Jack Beechum in The Memory of Old Jack, “It’s not a tragedy when a man dies at the end of his life.”

On the other hand, it is indeed a tragedy—the worst imaginable tragedy—when a child dies at the beginning of his or her life. And as a physician, this is my daily reality: children get sick and some of them die. And we depend on the “mechanical room,” the “mechanical light,” the tubes and needles, all the knowledge and technology that we can muster, to intervene where we can.

The hospital, and especially the operating room, is a decidedly anti-agrarian setting, fully integrated into and dependent upon the petrochemical, techno-industrial economy, and in many ways beholden to the “economics of greed.”

But what choice do we have?

*

To this question, I do not have an answer. At least not a settled one. But I believe it begins with discovering new ways of seeing, which, in turn, begins by paying attention. That is to say, by looking.

And so I take as my starting place the instruction from Berry’s poem “How to be a Poet”:

Make a place to sit down.

Sit down. Be quiet.

If we do, we may find that, like Old Jack Beechum, we will finally be able to “see what needs to be done.”

Jim Wood lives in Baton Rouge, Louisiana with his wife and their five children.